Historical criticism: Difference between revisions

m Bot: Migrating 12 interwiki links, now provided by Wikidata on d:q508091 (Report Errors) |

→Views on higher-criticism: removed statement that has nothing to do with historical criticism -- Habermas has written many books, but none having anything to do with the bible... |

||

| Line 374: | Line 374: | ||

Higher criticism was recognized to varying extents, by [[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox Jews]] and many traditional [[Christians]], yet they often found that higher critics gave unsatisfactory or even [[heresy|heretical]] interpretations. In particular, religious conservatives object to the [[Rationalism|rationalistic]] and [[Naturalism (philosophy)|naturalistic]] [[presupposition]]s of a large number of practitioners of higher criticism, which lead to conclusions that conservative scholars find unscientific. |

Higher criticism was recognized to varying extents, by [[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox Jews]] and many traditional [[Christians]], yet they often found that higher critics gave unsatisfactory or even [[heresy|heretical]] interpretations. In particular, religious conservatives object to the [[Rationalism|rationalistic]] and [[Naturalism (philosophy)|naturalistic]] [[presupposition]]s of a large number of practitioners of higher criticism, which lead to conclusions that conservative scholars find unscientific. |

||

[[Pope Leo XIII]] (1810–1903) condemned secular [[biblical criticism|biblical scholarship]] in his encyclical ''[[Providentissimus Deus]]'' while affirming the need for a balanced historical study of the Scriptures.<ref>Fogarty, page 40.</ref> However, in 1943 [[Pope Pius XII]] gave license to the new scholarship in his encyclical ''[[Divino Afflante Spiritu]]'': "[T]extual criticism ... [is] quite rightly employed in the case of the Sacred Books ... Let the interpreter then, with all care and without neglecting any light derived from recent research, endeavor to determine the peculiar character and circumstances of the sacred writer, the age in which he lived, the sources written or oral to which he had recourse and the forms of expression he employed." <ref>[http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xii/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xii_enc_30091943_divino-afflante-spiritu_en.html Encyclical ''Divino Afflante Spiritu''], 1943.</ref> |

[[Pope Leo XIII]] (1810–1903) condemned secular [[biblical criticism|biblical scholarship]] in his encyclical ''[[Providentissimus Deus]]'' while affirming the need for a balanced historical study of the Scriptures.<ref>Fogarty, page 40.</ref> However, in 1943 [[Pope Pius XII]] gave license to the new scholarship in his encyclical ''[[Divino Afflante Spiritu]]'': "[T]extual criticism ... [is] quite rightly employed in the case of the Sacred Books ... Let the interpreter then, with all care and without neglecting any light derived from recent research, endeavor to determine the peculiar character and circumstances of the sacred writer, the age in which he lived, the sources written or oral to which he had recourse and the forms of expression he employed." <ref>[http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xii/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xii_enc_30091943_divino-afflante-spiritu_en.html Encyclical ''Divino Afflante Spiritu''], 1943.</ref> |

||

Today, many [[Evangelicalism|Evangelical]] Protestants oppose the methods of the higher criticism, and hold that the Bible is divinely inspired and incapable of error, at least in its original form.<ref name="JInt"/><ref>[http://www.bible-researcher.com/chicago1.html Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> Within academia, the new [[hermeneutics]] inspired by [[critical theory]] has eclipsed earlier critical approaches such as higher criticism.<ref>IVP New Bible Commentary 21st Century edition. p11</ref> |

Today, many [[Evangelicalism|Evangelical]] Protestants oppose the methods of the higher criticism, and hold that the Bible is divinely inspired and incapable of error, at least in its original form.<ref name="JInt"/><ref>[http://www.bible-researcher.com/chicago1.html Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> Within academia, the new [[hermeneutics]] inspired by [[critical theory]] has eclipsed earlier critical approaches such as higher criticism.<ref>IVP New Bible Commentary 21st Century edition. p11</ref> |

||

Revision as of 05:16, 10 March 2013

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

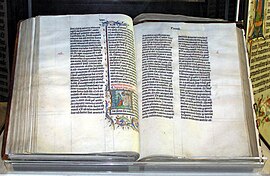

Historical criticism, also known as the historical-critical method or higher criticism, is a branch of literary criticism that investigates the origins of ancient text in order to understand "the world behind the text".[1]

The primary goal of historical criticism is to ascertain the text's primitive or original meaning in its original historical context and its literal sense or sensus literalis historicus. The secondary goal seeks to establish a reconstruction of the historical situation of the author and recipients of the text. This may be accomplished by reconstructing the true nature of the events in which the text describes. An ancient text may also serve as a document, record or source for reconstructing the ancient past which may also serve as a chief interest to the historical critic. In regards to Semitic biblical interpretation, the historical critic would be able to interpret "The Literature of Israel" as well as "The History of Israel".[2]

In 18th century Biblical criticism, the term higher criticism was commonly used in mainstream scholarship [3] in contrast with lower criticism. In the 21st century, historical criticism is the more commonly used term for higher criticism, while textual criticism is more common than the loose expression lower criticism.[4]

Historical criticism began in the 17th century and gained popular recognition in the 19th and 20th centuries. The perspective of the early historical critic was rooted in Protestant reformation ideology, in as much as their approach to biblical studies were free from the influence of traditional interpretation.[5] Where historical investigation was unavailable, historical criticism rested on philosophical and theological interpretation. With each passing century, historical criticism became refined into various methodologies used today: source criticism, form criticism, redaction criticism, tradition criticism, canonical criticism, and related methodologies.[2]

Historical critical methods

Historical-critical methods are the specific procedures [1] used to examine the text’s historical origins, such as: the time, the place in which the text was written, its sources, the events, dates, persons, places, things, and customs that are mentioned or implied in the text.[2]

The approach of Historical-critical methods typifies the following: (1) that reality is uniform and universal, (2) that reality is accessible to human reason and investigation (3) that all events historical and natural are interconnected and comparable to analogy, (4) that humanity’s contemporary experience of reality can provide objective criteria to what could or could not have happened in past events.[1]

Application

Application of the historical critical method, in biblical studies, investigates the books of the Hebrew Bible as well as the New Testament. Historical critics compare texts to other texts written around the same time. An example of this is when modern biblical scholarship has attempted to understand the Book of Revelation in its 1st century historical context, by identifying its literary genre with Jewish and Christian apocalyptic literature.

In regards to the Gospels, higher criticism deals with the synoptic problem, the relations among Matthew, Mark, and Luke. In some cases, such as with several Pauline epistles, higher criticism can confirm the traditional understanding of authorship or contradict church tradition as it has with the Gospels and 2 Peter.

In Classical studies, the 19th century approach to higher criticism set aside "efforts to fill ancient religion with direct meaning and relevance and devoted itself instead to the critical collection and chronological ordering of the source material."[6] Thus, higher criticism, whether biblical, classical, Byzantine or medieval, focuses on the source documents to determine who wrote it, when it was written, and where.

Historical/higher criticism has also been applied to other religious writings from Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, as well as the Qur'an.

Methodologies

| * | includes most of Leviticus |

| † | includes most of Deuteronomy |

| ‡ | "Deuteronomic history": Joshua, Judges, 1 & 2 Samuel, 1& 2 Kings |

Historical criticism comprises several disciplines which include:[2]

Source criticism

Source criticism is the search for the original sources which lie behind a given biblical text. It can be traced back to the 17th century French priest Richard Simon, and its most influential product is undoubtably Julius Wellhausen's Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels (1878), whose "insight and clarity of expression have left their mark indelibly on modern biblical studies."[7]

Form criticism

Form criticism breaks the Bible down into sections (pericopes, stories) which are analyzed and categorized by genres (prose or verse, letters, laws, court archives, war hymns, poems of lament, etc.). The form critic then theorizes on the pericope's Sitz im Leben ("setting in life"), the setting in which it was composed and, especially, used.[8] Tradition history is a specific aspect of form criticism which aims at tracing the way in which the pericopes entered the larger units of the biblical canon, and especially the way in which they made the transition from oral to written form. The belief in the priority, stability, and even detectability, of oral traditions is now recognised to be so deeply questionable as to render tradition history largely useless, but form criticism itself continues to develop as a viable methodology in biblical studies.[9]

Redaction criticism

Redaction criticism studies "the collection, arrangement, editing and modification of sources", and is frequently used to reconstruct the community and purposes of the author/s of the text.[10]

Radical criticism

At the end of the 19th Century, there have been advocates of higher criticism, who strenuously tried to avoid any trace of dogma or theological bias when reconstructing a past reality. This has led to the branch of Radical Criticism, pursued by historical critics most skeptical of ecclesial tradition and dismissive toward sympathetic scholarship. Radical criticism has projected the concept that Jesus never existed,[1] nor his apostles. Radical critics have also attempted to show that none of the Pauline epistles are authentic; that Paul is nothing more than a controverted (conflated) authorial token.

History of higher criticism

The Dutch scholars Desiderius Erasmus (1466? – 1536) and Benedict Spinoza (1632–1677) are usually credited as the first to study the Bible in this way.[11] When applied to the Bible, the historical-critical method is distinct from the traditional, devotional approach.[12] In particular, while devotional readers concern themselves with the overall message of the Bible, historians examine the distinct messages of each book in the Bible.[12] Guided by the devotional approach, for example, Christians often combine accounts from different gospels into single accounts, whereas historians attempt to discern what is unique about each gospel, including how they are different.[12]

The phrase "higher criticism" became popular in Europe from the mid-18th century to the early 20th century, to describe the work of such scholars as Jean Astruc (mid-18th century), Johann Salomo Semler (1725–91), Johann Gottfried Eichhorn (1752–1827), Ferdinand Christian Baur (1792–1860), and Julius Wellhausen (1844–1918).[13] In academic circles today, this is the body of work properly considered "higher criticism", though the phrase is sometimes applied to earlier or later work using similar methods.

Higher criticism originally referred to the work of German biblical scholars of the Tübingen School. After the path-breaking work on the New Testament by Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), the next generation – which included scholars such as David Friedrich Strauss (1808–74) and Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–72) – in the mid-19th century analyzed the historical records of the Middle East from Christian and Old Testament times in search of independent confirmation of events related in the Bible. These latter scholars built on the tradition of Enlightenment and Rationalist thinkers such as John Locke, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Gotthold Lessing, Gottlieb Fichte, G. W. F. Hegel and the French rationalists.

These ideas were imported to England by Samuel Taylor Coleridge and, in particular, by George Eliot's translations of Strauss's The Life of Jesus (1846) and Feuerbach's The Essence of Christianity (1854). In 1860 seven liberal Anglican theologians began the process of incorporating this historical criticism into Christian doctrine in Essays and Reviews, causing a five year storm of controversy which completely overshadowed the arguments over Darwin's newly published On the Origin of Species. Two of the authors were indicted for heresy and lost their jobs by 1862, but in 1864 had the judgement overturned on appeal. La Vie de Jésus (1863), the seminal work by a Frenchman, Ernest Renan (1823–92), continued in the same tradition as Strauss and Feuerbach. In Catholicism, L'Evangile et l'Eglise (1902), the magnum opus by Alfred Loisy against the Essence of Christianity of Adolf von Harnack and La Vie de Jesus of Renan, gave birth to the modernist crisis (1902–61). Some scholars, such as Rudolf Bultmann have used higher criticism of the Bible to "demythologize" it.

Higher criticism interpretations

Scholars of higher criticism have sometimes upheld and sometimes challenged the traditional authorship of various books of the Bible.[14] Details of the arguments regarding this issue are addressed more specifically in the articles about each book.

Old Testament

Around the end of the 18th century Johann Gottfried Eichhorn, "the founder of modern Old Testament criticism", produced works of "investigation of the inner nature of the Old Testament with the help of the Higher Criticism". Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher also influenced the development of Higher Criticism.

A group of German biblical scholars at Tübingen University formed the Tübingen school of theology under the leadership of Ferdinand Christian Baur, with important works being produced by Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach and David Strauss. In the early 19th century they sought independent confirmation of the events related in the Bible through Hegelian analysis of the historical records of the Middle East from Christian and Old Testament times.[15][16]

Their ideas were brought to England by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, then in 1846 Mary Ann Evans translated David Strauss's sensational Leben Jesu as the Life of Jesus Critically Examined, a quest for the historical Jesus. In 1854 she followed this with a translation of Feuerbach's even more radical Essence of Christianity which held that the idea of God was created by man to express the divine within himself, though Strauss attracted most of the controversy.[15] The loose grouping of Broad Churchmen in the Church of England was influenced by the German higher critics. In particular, Benjamin Jowett visited Germany and studied the work of Baur in the 1840s, then in 1866 published his book on The Epistles of St Paul, arousing theological opposition. He then collaborated with six other theologians to publish their Essays and Reviews in 1860. The central essay was Jowett's On the Interpretation of Scripture which argued that the Bible should be studied to find the authors' original meaning in their own context rather than expecting it to provide a modern scientific text.[17][18]

Table of interpretations: Old Testament

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

New Testament

Table of interpretations: New Testament

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Qur'an

Modern higher criticism is just beginning for the Qur'an. This scholarship questions some traditional claims about its composition and content, contending that the Qur'an incorporates material from both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament; however, other scholars argue that it cites examples from previous texts, as the New Testament did to the Old Testament.

Attempts at higher criticism of the Qur'an have met with hostility and resistance among traditional Islamic scholars, who contend that using the methods of higher criticism either implies that the Qur'an was written by human beings—a position incompatible with the generally accepted tenet that the Qur'an is the literal word of God revealed to Muhammad—or that the Qur'an was created, a position held by the Mu'tazili school of early Islam but rejected by the Ash'ari school that forms the basis for mainstream Islamic thought today. Attempts to resolve the issue or sidestep it, such as Nasr Abu Zayd's attempt to treat the Qur'an as a divinely revealed naṣṣ (text) in the human Arabic language and thus subject to higher criticism and hermeneutics, have not been widely accepted.

Controversy of critical methods

Views on higher-criticism

Higher criticism was recognized to varying extents, by Orthodox Jews and many traditional Christians, yet they often found that higher critics gave unsatisfactory or even heretical interpretations. In particular, religious conservatives object to the rationalistic and naturalistic presuppositions of a large number of practitioners of higher criticism, which lead to conclusions that conservative scholars find unscientific.

Pope Leo XIII (1810–1903) condemned secular biblical scholarship in his encyclical Providentissimus Deus while affirming the need for a balanced historical study of the Scriptures.[30] However, in 1943 Pope Pius XII gave license to the new scholarship in his encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu: "[T]extual criticism ... [is] quite rightly employed in the case of the Sacred Books ... Let the interpreter then, with all care and without neglecting any light derived from recent research, endeavor to determine the peculiar character and circumstances of the sacred writer, the age in which he lived, the sources written or oral to which he had recourse and the forms of expression he employed." [31]

Today, many Evangelical Protestants oppose the methods of the higher criticism, and hold that the Bible is divinely inspired and incapable of error, at least in its original form.[12][32] Within academia, the new hermeneutics inspired by critical theory has eclipsed earlier critical approaches such as higher criticism.[33]

Views on historical-methods

The historical-critical method of Biblical scholarship is taught widely in Western nations, including in many seminaries.[12] According to Ehrman, most lay Christians are unaware of how different this particular academic view of the Bible is from their own.[12] Conservative evangelical schools, however, often reject this approach, teaching instead that the Bible is completely inerrant in all matters (in contrast to the less conservative Protestant view that it is infallible only in matters relating to personal salvation, a doctrine called biblical infallibility) and that it reflects explicit divine inspiration.[12] However, the Catholic Church, while teaching inerrancy,[34] also allows for more nuance in interpretation than would conservative Evangelical schools, because of its historical understanding of the "four senses of Scripture".[35] In The Pontifical Biblical Commission's "Interpretation of the Bible in the Church," the need for historical criticism is clearly expressed and affirmed.

In regards to Protestant historical-criticism, the movement of rationalism as promoted by Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677), held that reason is the determiner of truth. Spinoza did not regard the Bible as divinely inspired, instead it was to be evaluated like any other book. Later rationalists also have rejected the authority of Scripture.[36]

See also

- Biblical criticism

- Biblical genres

- Diplomatics

- Documentary hypothesis

- Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy

- Historical-grammatical method

- Journal of Higher Criticism

- Textual criticism (lower criticism)

- Synoptic Problem

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d Soulen, Richard N. (2001). Handbook of biblical criticism (3rd ed., rev. and expanded. ed.). Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 78. ISBN 0-664-22314-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Soulen, Richard N. (2001). John Knox. p. 79.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Hahn, general editor, Scott (2009). Catholic Bible dictionary (1st ed. ed.). New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-51229-5.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|first=has generic name (help); Text "Methods of Biblical criticism" ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Soulen, Richard N. (2001). John Knox. pp. 108, 190.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Gerhard Ebeling. Word and Faith. Philadelphia, Fortress Press, 1963

- ^ Burkert, Greek Religion (1985), Introduction.

- ^ Antony F. Campbell, SJ, "Preparatory Issues in Approaching Biblical Texts", in The Hebrew Bible in Modern Study, p.6. Campbell renames source criticism as "origin criticism".

- ^ Bibledudes.com

- ^ Yair Hoffman, review of Marvin A. Sweeney and Ehud Ben Zvi (eds.), The Changing Face of Form-Criticism for the Twenty-First Century, 2003

- ^ Religious Studies Department, Santa Clara University.

- ^ Will Durant, The Story of Philosophy, p. 125, Touchstone, 1961, ISBN 0-671-20159-X,

- ^ a b c d e f g Ehrman, Bart D.. Jesus, Interrupted, HarperCollins, 2009. ISBN 0-06-117393-2

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2007

- ^ Dates for the Sacred Texts of the Jewish and Christian Traditions: Athabasca University

- ^ a b Glenn Everett, Associate Professor of English, University of Tennessee at Martin (1988). "The Higher Critics". The Victorian Web. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Tubingen School". Retrieved 2007-11-06.

- ^ Glenn Everett, Associate Professor of English, University of Tennessee at Martin (1988). "Essays and Reviews (1860)". The Victorian Web. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Josef L. Altholz, Professor of History, University of Minnesota (1976). "The Warfare of Conscience with Theology". The Mind and Art of Victorian England. Victorian Web. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ New American Bible: Job

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Dates for the Sacred Texts of the Jewish and Christian Traditions

- ^ Miller, Stephen M., Huber, Robert V. (2004). The Bible: A History. Good Books. p. 33. ISBN 1-56148-414-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ New American Bible: John

- ^ see Signs Gospel for more on reconstruction of original John

- ^ Vindicating the Integrity of John's Gospel

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (2004). The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. New York: Oxford, p.385; Beverly Roberts Gaventa, First and Second Thessalonians, Westminster John Knox Press, 1998, p.93; Vincent M. Smiles, First Thessalonians, Philippians, Second Thessalonians, Colossians, Ephesians, Liturgical Press, 2005, p.53; Udo Schnelle, translated by M. Eugene Boring, The History and Theology of the New Testament Writings (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1998), pp. 315–325; M. Eugene Boring, Fred B. Craddock, The People's New Testament Commentary, Westminster John Knox Press, 2004 p652; Joseph Francis Kelly, An Introduction to the New Testament for Catholics, Liturgical Press, 2006 p.32

- ^ http://www.religion-online.org/showchapter.asp?title=531&C=563 Richard Heard, Introduction To The New Testament

- ^ New American Bible: James

- ^ Carson, D.A., and Douglas J. Moo. An Introduction to the New Testament, second edition. HarperCollins Canada; Zondervan: 2005. ISBN 0-310-23859-5, ISBN 978-0-310-23859-1. p.659.

- ^ New American Bible: Jude

- ^ Fogarty, page 40.

- ^ Encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu, 1943.

- ^ Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy

- ^ IVP New Bible Commentary 21st Century edition. p11

- ^ [1], Chapter III, par. 11.

- ^ [2]

- ^

Klein, William W. William Wade (1993). Introduction to Biblical Interpretation. Dallas, Tex.: Word Pub. ISBN 0-8499-0774-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Page 43

References

- Gerald P. Fogarty, S.J. American Catholic Biblical Scholarship: A History from the Early Republic to Vatican II, Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1989, ISBN 0-06-062666-6. Nihil obstat by Raymond E. Brown, S.S., and Joseph A. Fitzmyer, S.J.

External links

- Rutgers University: Synoptic Gospels Primer: introduction to the history of literary analysis of the Greek gospels, and aids in confronting the range of factors that need to be taken into consideration in accounting for the literary relationship of the first three gospels.

- Journal of Higher Criticism

- From the Divine Oracle to Higher Criticism

- Catholic Encyclopedia article "Biblical Criticism (Higher)"

- Dictionary of the history of Ideas – Modernism and the Church

- Teaching Bible based on Higher Criticism

- "Historical Criticism and the Evangelical" by Grant Osborne

- "From the Divine Oracle to Higher Criticism" from The Warfare of Science With Theology by Andrew White, 1896

- Catholic Encyclopedia article (1908) "Biblical Criticism (Higher)"

- Dictionary of the history of Ideas: Modernism in the Christian Church

- Radical criticism, link to articles in English

- Library of latest modern books of biblical studies and biblical criticism