Hispanic and Latino Americans: Difference between revisions

Comayagua99 (talk | contribs) |

Comayagua99 (talk | contribs) →Cultural influence: Added information on cuisine |

||

| Line 636: | Line 636: | ||

*[[ESPN Deportes]] and [[Fox Deportes]], two Spanish-language sports television networks. |

*[[ESPN Deportes]] and [[Fox Deportes]], two Spanish-language sports television networks. |

||

===Cuisine=== |

|||

[[File:Cubanfood.jpg|thumb|right|Cuban cuisine common in Florida: [[Ropa vieja]] with [[black bean]]s, rice and [[yuca]]]] |

|||

[[File:Papa_chevos_burrito.jpg|thumb|right|The Mexican [[burrito]] is now one of the most popular food items in the US]] |

|||

Hispanics, particularly Cuban, Mexican, and Puerto Ricans, have influenced [[American cuisine]] and American eating habits. [[Mexican cuisine]] is now popular across the US, making [[tortilla]]s and [[salsa]] more popular than hamburger buns and [[ketchup]]. [[Tortilla chip]]s have also surpassed [[potato chip]]s in annual sales, and [[fried plantain|plantain chip]]s popular in [[Caribbean]] cuisines has continued to grow in popularity.<ref>http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2013/oct/17/hispanic-influence-tortillas-take-over-burger-buns/</ref> |

|||

Due to the large Mexican American population in the Southwestern United States, and its proximity to [[Mexico]], Mexican food there is believed to be some of the best in the US. [[Cuban]]s brought [[Cuban cuisine]] to [[Miami]], and today, [[cortado|cortadito]]s, pastelitos de guayaba, and [[empanada]]s are common mid-day snacks. Cuban culture has changed Miami's coffee drinking habits, and today a [[café con leche]] or a cortadito is commonly had, often with a pastelito (pastry) at one of the city's numerous coffee shops.<ref>http://nbclatino.com/2013/10/17/latino-other-ethnic-influences-changing-americas-food-choices/</ref> The [[Cuban sandwich]] was invented in Miami, and is now also a staple and icon of the city's cuisine and culture.<ref>http://www.foodbycountry.com/Spain-to-Zimbabwe-Cumulative-Index/United-States-Latino-Americans.html</ref> |

|||

=== Intermarriage === |

=== Intermarriage === |

||

Revision as of 16:25, 18 June 2014

Error: no context parameter provided. Use {{other uses}} for "other uses" hatnotes. (help). Template:Distinguish2

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| All areas of the United States | |

| Languages | |

| Spanish • English • Indigenous languages | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholicism;[1] large minority of Protestantism[1] · Indigenous religion · Jehovah's Witnesses · Mormonism Judaism, Islam, Agnosticism · Atheism[1][2] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Latin Americans, Native Americans, Haitian Americans, Belizean Americans, White Latin Americans, Criollos, Afro-Latin Americans, Asian Latin Americans, Mestizos, Métis, Mulattoes, Pardos, Castizos and others. It is important to note that some of the prior groups i.e. Belizean Americans and Haitian Americans are not officially considered Hispanic or Latinos by the U.S. Government and are not included in any official surveys [3] |

Hispanics Spanish: hispanos [isˈpanos], [hispánicos] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) [isˈpanikos], or Latinos [latinos] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) are an ethnolinguistic group of Americans with origins in the countries of Latin America and Spain.[5][6][7] More generally it includes all persons in the United States who self-identify as Hispanic or Latino.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14] Latin American population has origins in all the continents and has ancestries including many Native American cultures,[15] Hispanic and Latino Americans are separate terms that are racially diverse, and as a result form an ethnic category, rather than a race.[13][16][17][18] In the 2010 Census, 53% Hispanics in the US self-identified as white, while 37% were Mestizos.

While the two terms are sometimes used interchangeably, Hispanic is a narrower term and refers mostly to persons of Spanish-speaking ancestry, while Latino is more frequently used to refer more generally to anyone of Latin American origin or ancestry, including Brazilians.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30] Hispanic thus includes Spanish speaking Latin Americans countries, excluding Brazilians (who speak Portuguese) while Latino includes both Spanish-speaking and Portuguese-speaking Latin Americans, but excluding Spain. The choice between the terms Latino and Hispanic among those of Spanish speaking ancestry is also associated with location: persons of Spanish speaking ancestry residing in the eastern United States tend to prefer the term Hispanic, whereas those in the West tend to prefer Latino.[12]

It is important to note that some of the prior groups such as Belizean Americans and Haitian Americans are not officially considered Hispanic or Latinos by the U.S. Government and are not included in any official surveys. Only the peoples from Spanish speaking Europe and the Spanish speaking Americas are officially considered Hispanic or Latinos. While recent books have suggested the expansion of this group, they have do not hold legal authority to change the official U.S. Census definition, which created this ethnic group.[3]

Hispanics or Latinos constitute 16.9% of the total United States population, or 53 million people,.[31] This figure includes 38 million Hispanophone Americans, making the US home to the largest community of Spanish speakers outside of Mexico according to the Pew Research Hispanic Center, having surpassed Argentina, Colombia, and Spain within the last decade.[32] Latinos overall are the second largest ethnic group, after non-Hispanic White Americans (a group composed of dozens of sub-groups, as is Hispanic and Latino Americans).[33] Hispanic and Latino Americans are the largest of all the minority groups, but Black Americans are the largest minority among the races, after White Americans in general (non-Hispanic and Hispanic).[34] Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans, Colombian Americans, Dominican Americans, Puerto Rican Americans, Spanish Americans, and Salvadoran Americans are some of the Hispanic and Latino American national origin groups.[35]

There have been people of Hispanic or Latino heritage in the territory of the present-day United States continuously[36][37][38][39] since the 1565 founding of St. Augustine, Florida, by the Spanish, the longest among European American ethnic groups and second-longest of all U.S. ethnic groups, after Native Americans to inhabit what is today the United States. Hispanics have also lived continuously in the Southwest since near the end of the 16th century, with settlements in New Mexico that began in 1598, and which were transferred to the area of El Paso, Texas, in 1680.[40] Spanish settlement of New Mexico resumed in 1692, and new ones were established in Arizona and California in the 18th century.[41][42] The Hispanic presence can even be said to date from half a century earlier than St. Augustine, if San Juan, Puerto Rico is considered to be the oldest Spanish settlement, and the oldest city, in the U.S.[43]

Terminology

| Part of a series on |

| Hispanic and Latino Americans |

|---|

The term Hispanic was adopted by the United States government in the early 1970s during the administration of Richard Nixon[44] after the Hispanic members of an interdepartmental Ad Hoc Committee to develop racial and ethnic definitions recommended that a universal term encompassing all Hispanic subgroups—including Central and South Americans—be adopted.[45] As the 1970 census did not include a question on Hispanic origin on all census forms—instead relying on a sample of the population via an extended form ("Is this person's origin or descent: Mexican; Puerto Rican; Cuban; Central or South American; Other Spanish; or None of these")[46]—the members of the Ad Hoc Committee wanted a common designation to better track the social and economic progress of the group vis-à-vis the general population.[45] The designation has since been used in local and federal employment, mass media, academia, and business market research. It has been used in the U.S. Census since 1980.[47] Because of the popularity of "Latino" in the western portion of the United States, the government adopted this term as well in 1997, and used it in the 2000 census.[12][13]

Previously, Hispanic and Latino Americans were categorized as "Spanish-Americans", "Spanish speaking Americans", and "Spanish surnamed Americans". However:

- Although a large majority of Hispanic and Latino Americans have Spanish ancestry, most are not of direct, "from-Spain-to-the-U.S."[48][49] Spanish descent; many are not primarily of Spanish or descent; and some are not of Spanish descent at all. People whose ancestors or who themselves arrived in the United States directly from Spain or are a tiny minority of the Hispanic or Latino population (see figures in this article), and there are Hispanic/Latino Americans who are of other European ancestries in addition to Spanish (e.g. Portuguese, Italian, German, and Middle Eastern, such as the Lebanese).[50]

- Most Hispanic and Latino Americans can speak Spanish, not all; and most Spanish speaking and speaking Americans are Hispanic or Latino, not all. E.g., Hispanic/Latino Americans often do not speak Spanish or by the third generation, and some Americans who are Spanish speaking or may not identify themselves with Spanish speaking Americans as an ethnic group.

- Not all Hispanic and Latino Americans have Spanish surnames, and most Spanish-surnamed Americans are Hispanic or Latino, not all. For example, non-Spanish surnamed Bill Richardson (former governor, Congressman, etc.), former National Football League (NFL) star Jim Plunkett, and Salma Hayek (actress) have Hispanic or Latino origin. Filipino Americans, and Pacific Islander Americans of Chamorro (Guamanians and Northern Mariana Islanders), Palauan, Micronesian (FSM), and Marshallese origin often have Spanish surnames, but have their own, non-Hispanic/Latino ethnic identities and origin. Likewise, while many Louisiana Creole people have Spanish surnames, they identify with the mostly French—though partially Spanish—culture of their region.

Neither term refers to race, as a person of Latino or Hispanic origin can be of any race.[13][51]

The U.S. government has defined Hispanic or Latino persons as being "persons who trace their origin [to] ...Central and South America, and other Spanish cultures".[12] The Census Bureau's 2010 census does provide a definition of the terms Latino or Hispanic and is as follows: “Hispanic or Latino” refers to a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish culture or origin regardless of race. It allows respondents to self-define whether they were Latino or Hispanic and then identify their specific country or place of origin.[52] On its website, the Census Bureau defines "Hispanic" or "Latino" persons as being "persons who trace their origin [to]... Spanish speaking Central and South America countries, and other Spanish cultures".[12][13][53]

These definitions thus arguably does not include Brazilian Americans,[12][13][54] especially since the Census Bureau classifies Brazilian Americans as a separate ancestry group from Hispanic or Latino.[55] The 28 Hispanic or Latino American groups in the Census Bureau's reports are the following:[13][35][56] Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Dominican; Central American: Costa Rican, Guatemalan, Honduran, Nicaraguan, Panamanian, Salvadoran, Other Central American; South American: Argentinian, Bolivian, Chilean, Colombian, Ecuadorian, Paraguayan, Peruvian, Uruguayan, Venezuelan, Other South American; Other Hispanic or Latino: Spaniard, Spanish, Spanish American, All other Hispanic.

One dictionary of American English maintains a distinction between the terms "Hispanic" and "Latino":

Though often used interchangeably in American English, Hispanic and Latino are not identical terms, and in certain contexts the choice between them can be significant. Hispanic, from the Latin word for "Spain," ...potentially encompass[es] all Spanish speaking peoples in both hemispheres and emphasiz[es] the common denominator of language among communities that sometimes have little else in common. Latino—which in Spanish means "Latin" but which as an English word is probably a shortening of the Spanish and Portuguese word latinoamericano—refers ...to persons or communities of Latin American origin. Of the two, only Latino can be used to refer to Brazilians, who are Latin American, but who do not speak Spanish, and only Hispanic can be used in referring to Spain and its history and culture; a native of Spain residing in the United States is a Hispanic, not a Latino, and one cannot substitute Latino in the phrase the Hispanic influence on native Mexican cultures without garbling the meaning. In practice, however, this distinction is of little significance when referring to residents of the United States, most of whom are of Latin American origin and can theoretically be called by either word.[57]

The AP Stylebook states that Latino is often the preferred term for a person from – or whose ancestors were from – a Spanish speaking land or culture or from Latin America. Latina is the feminine form. Follow the person's preference. Use a more specific identification when possible, such as Cuban, Puerto Rican, Brazilian or Mexican-American. Of Hispanic the AP Stylebook states: Hispanic – A person from – or whose ancestors were from – a Spanish speaking land or culture. Latino and Latina are sometimes preferred. Follow the person’s preference.[30] Some federal and local government agencies and non-profit organizations may include Brazilians and Portuguese in their definition of Hispanic. The U.S. Department of Transportation defines Hispanic as, "persons of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Dominican, Central or South American, or other Spanish or Portuguese culture or origin, regardless of race".[8] This definition has been adopted by the Small Business Administration as well as by many federal, state, and municipal agencies for the purposes of awarding government contracts to minority owned businesses.[9]

The Congressional Hispanic Caucus, which was founded by Hispanic Puerto Rican Herman Badillo, and the Congressional Hispanic Conference include representatives of Spanish and Portuguese descent and Hispanic and Latino Americans. The Hispanic Society of America is dedicated to the study of the arts and cultures of Spain, Portugal, and Latin America. The Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities, which proclaims itself the champion of Hispanic success in higher education, has member institutions in the US, Puerto Rico, Latin America, Spain, and Portugal. Even though the term "Hispanic" is related to "Spanish," many Hispanic Americans do not speak Spanish.

History

This section needs expansion with: more about the 19th and 20th centuries. You can help by adding to it. (January 2010) |

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 116,943 | — | |

| 1880 | 393,555 | — | |

| 1900 | 503,189 | — | |

| 1910 | 797,994 | 58.6% | |

| 1920 | 1,286,154 | 61.2% | |

| 1930 | 1,653,987 | 28.6% | |

| 1940 | 2,021,820 | 22.2% | |

| 1950 | 3,231,409 | 59.8% | |

| 1960 | 5,814,784 | 79.9% | |

| 1970 | 8,920,940 | 53.4% | |

| 1980 | 14,608,673 | 63.8% | |

| 1990 | 22,354,059 | 53.0% | |

| 2000 | 35,305,818 | 57.9% | |

| 2010 | 50,477,594 | 43.0% | |

| 2012 (est.) | 52,961,017 | 4.9% | |

| Sources: | |||

16th and 17th century

A continuous Hispanic/Latino presence in the territory of the United States has existed since the 16th century,[36][37][38][39] earlier than any other group after the Native Americans. Spaniards pioneered the present-day United States. The first confirmed European landing in the continental U.S. was by Juan Ponce de León, who landed in 1513 at a lush shore he christened La Florida.

Within three decades of Ponce de León's landing, the Spanish became the first Europeans to reach the Appalachian Mountains, the Mississippi River, the Grand Canyon and the Great Plains. Spanish ships sailed along the East Coast, penetrating to present-day Bangor, Maine, and up the Pacific Coast as far as Oregon. From 1528 to 1536, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and three other castaways from a Spanish expedition (including an African named Estevanico) journeyed all the way from Florida to the Gulf of California, 267 years before the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

In 1540 Hernando de Soto undertook an extensive exploration of the present U.S., and in the same year Francisco Vásquez de Coronado led 2,000 Spaniards and Mexican Indians across today's Arizona–Mexico border and traveled as far as central Kansas, close to the exact geographic center of what is now the continental United States. Other Spanish explorers of the US make up a long list that includes, among others: Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón, Pánfilo de Narváez, Sebastián Vizcaíno, Gaspar de Portolà, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Tristán de Luna y Arellano and Juan de Oñate, but also non-Spanish explorers working for the Spanish Crown like Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo. In all, Spaniards probed half of today's lower 48 states before the first English colonization attempt at Roanoke Island in 1585.

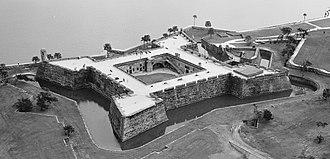

The Spanish created the first permanent European settlement in the continental United States, at St. Augustine, Florida, in 1565. Santa Fe, New Mexico also predates Jamestown, Virginia (founded in 1607) and Plymouth Colony (of Mayflower and Pilgrims fame; founded in 1620). Later came Spanish settlements in San Antonio, Texas, Tucson, Arizona, San Diego, California, Los Angeles, California and San Francisco, California, to name just a few.

18th and 19th century

Two iconic American stories have Spanish antecedents, too. Almost 80 years before John Smith's alleged rescue by Pocahontas, a man by the name of Juan Ortiz told of his remarkably similar rescue from execution by an Indian girl. Spaniards also held a thanksgiving—56 years before the famous Pilgrims festival—when they feasted near St. Augustine with Florida Indians, probably on stewed pork and garbanzo beans. As late as 1783, at the end of the American Revolutionary War (a conflict in which Spain aided and fought alongside the United States), Spain held claim to roughly half of today's continental United States. From 1819 to 1848, the United States (through treaties, purchase, diplomacy, and the Mexican-American War) increased its area by roughly a third at Spanish and Mexican expense, acquiring three of today's four most populous states—California, Texas and Florida.

20th century

The Hispanic and Latino role in the history and present of the United States is addressed in more detail below (See Notables and their contributions). On September 17, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson designated a week in mid-September as National Hispanic Heritage Week, with Congress's authorization. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan extended the observance to a month, designated Hispanic Heritage Month.[59]

Demographics

| Hispanic Group | Population | % of Hispanics |

|---|---|---|

| 31,798,258 | 63.0 | |

| 4,623,716 | 9.2 | |

| 1,785,547 | 3.5 | |

| 1,648,968 | 3.3 | |

| 1,414,703 | 2.8 | |

| 1,044,209 | 2.1 | |

| 908,734 | 1.8 | |

| 635,253 | 1.3 | |

| 633,401 | 1.3 | |

| 564,631 | 1.1 | |

| 531,358 | 1.1 | |

| 348,202 | 0.7 | |

| 224,952 | 0.4 | |

| 215,023 | 0.4 | |

| 165,456 | 0.3 | |

| 126,810 | 0.3 | |

| 126,418 | 0.3 | |

| 99,210 | 0.2 | |

| 56,884 | 0.1 | |

| 20,023 | - | |

| All other | 3,505,838 | 6.9 |

| Total | 50,477,594 | 100 |

As of 2011, Hispanics accounted for 16.7% of the national population, or around 52 million people.[31] The Hispanic growth rate over the April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2007 period was 28.7%—about four times the rate of the nation's total population (at 7.2%).[61] The growth rate from July 1, 2005 to July 1, 2006 alone was 3.4%[62]—about three and a half times the rate of the nation's total population (at 1.0%).[61] Based on the 2010 census, Hispanics are now the largest minority group in 191 out of 366 metropolitan areas in the US.[63] The projected Hispanic population of the United States for July 1, 2050 is 132.8 million people, or 30.2% of the nation's total projected population on that date.[64]

Geographic distribution

Of the nation's total Hispanic or Latino population, 49% (21.5 million) live in California or Texas.[65]

The majority of Mexican Americans are concentrated in the Southwest and the West Coast/West, primarily in California, Texas, Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah. The majority of the Hispanic population in the Southeast and Great Plains (Plains States), concentrated in Florida, are of Cuban origin; However, the Mexican, Dominican and Puerto Rican populations have risen significantly in this region since the mid-1990s.

The Hispanic population in the Northeast, concentrated in New York, New Jersey, and Southeastern Pennsylvania, is composed mostly of Hispanics of Dominican and Puerto Rican origin. The remainder of Hispanics and Latinos may be found throughout the country, though South Americans tend to concentrate on the East Coast and Central Americans on the West Coast. Nevertheless, since the 1990s, several cities on the East Coast have seen often impressive increases in their Mexican population, namely Miami and Philadelphia.

National origin

As of 2007, some 64% of the nation's Hispanic population are of Mexican origin (see table). Another 9% are of Puerto Rican origin, with about 3% each of Cuban, Salvadoran and Dominican origins. The remainder are of other Central American or South American origin, or of origin directly from Spain. 60.2% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans were born in the United States.[68]

There are few recent immigrants directly from Spain. In the 2000 Census, 299,948 Americans, of whom 83% were native-born,[69] specifically reported their ancestry as Spaniard.[70] Additionally, in the 2000 Census some 2,187,144 Americans reported "Spanish" as their ancestry.

In northern New Mexico and southern Colorado, there is a large portion of Hispanics who trace their ancestry to Spanish settlers of the late 16th century through the 17th century. People from this background often self-identify as "Hispanos", "Spanish", or "Hispanic". Many of these settlers also intermarried with local Amerindians, creating a Mestizo population.[71] Likewise, southern Louisiana is home to communities of people of Canary Islands descent, known as Isleños, in addition to other people of Spanish ancestry.

Race

Hispanic or Latino origin is independent of race and is termed "ethnicity" by the United States Census Bureau.

The majority of Hispanic and Latino Americans are White. According to the 2007 American Community Survey, 92% of Hispanic and Latinos were White. The largest numbers of White Hispanics come from within the Argentine, Colombian, Cuban, Mexican, Spanish, and Venezuelan communities.[72][73]

A significant portion of the Hispanic and Latino population also identifies as Mestizo. Mestizo is not listed as a racial category in the U.S. Census. According to the 2010 United States Census, 36.7% of Hispanic/Latino Americans identify as "some other race", such as Mestizo American.[74]

Notable contributions

Hispanic and Latino Americans have made distinguished contributions to the United States in all major fields, such as politics, the military, music, literature, philosophy, sports, business and economy, and science.[76]

Arts and entertainment

In 1995, the American Latino Media Arts Award, or ALMA Award was created. It's a distinction given to Latino performers (actors, film and television directors, and musicians) by the National Council of La Raza.

Music

There are many Hispanic American musicians that have achieved international fame, such as Jennifer López, Joan Baez, Linda Ronstadt, Carmen Miranda, Zack de la Rocha, Fergie, Gloria Estefan, Celia Cruz, Tito Puente, Kat DeLuna, Selena, Ricky Martin, Marc Anthony, Carlos Santana, Shakira, Christina Aguilera, Pitbull, Los Lonely Boys, Frankie J, Jerry García, Robert Trujillo, Aventura and Tom Araya.

Among the Hispanic American musicians who were pioneers in the early stages of rock and roll were Ritchie Valens, who scored several hits, most notably "La Bamba" and Herman Santiago wrote the lyrics to the iconic rock and roll song "Why Do Fools Fall in Love". Another song that became popular in the United States and is heard during the Holiday/Christmas season is "Feliz Navidad" by José Feliciano.

The most prestigious Latin music awards in the United States are the Latin Grammy Awards, launched in 2000. Billboard Magazine also honors these artists, with the Billboard Latin Music Awards. The latter's nominees and winners are a result of performance on Billboard's sales and radio charts, while the Latin Grammy Awards nominees and winners are selected by the Latin Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences (LARAS).

Film, radio, television, and theatre

Hispanics and Latinos have also contributed some prominent actors and others in the film industry, a few of whom includes actors José Ferrer, the first Hispanic actor to win an Academy Award for his role in Cyrano de Bergerac, Anthony Quinn, Cameron Diaz, Martin Sheen, Cheech Marín, Salma Hayek, Dolores del Río, Anita Page, Rita Hayworth, Antonio Banderas, Raquel Welch, Benicio del Toro, Eva Mendes, Zoe Saldana, Edward James Olmos, Maria Montez, Ramón Novarro, Ricardo Montalbán, Cesar Romero, Rosie Perez, Katy Jurado, Rita Moreno, Lupe Vélez, Esai Morales, Andy García, Rosario Dawson, John Leguizamo, and, behind the camera, directors Robert Rodriguez, Guillermo del Toro, Alfonso Cuarón and Brett Ratner (also producers and cinematographers) and Luis Valdez.

In standup comedy, Paul Rodríguez, Greg Giraldo, Cheech Marin, George Lopez, Freddie Prinze, Carlos Mencia, John Mendoza, and others are prominent.

Some of the Hispanic or Latino actors who achieved notable success in U.S. television include Desi Arnaz, Lynda Carter, Jimmy Smits, Selena Gomez, Carlos Pena, Jr., Eva Longoria, Sofía Vergara, Benjamin Bratt, Ricardo Montalbán, America Ferrera, Erik Estrada, Cote de Pablo, Freddie Prinze, Lauren Vélez, and Charlie Sheen. Kenny Ortega is an Emmy Award-winning producer, director, and choreographer who has choreographed many major television events such as Super Bowl XXX, the 72nd Academy Awards, and Michael Jacksons memorial service.

Hispanics and Latinos are underrepresented in U.S. television, radio, and film. This is combatted by organizations such as the Hispanic Organization of Latin Actors (HOLA), founded in 1975; and National Hispanic Media Coalition (NHMC), founded in 1986.[77] Together with numerous Latino civil rights organizations, the NHMC led a "brownout" of the national television networks in 1999, after discovering that there were no Latinos in any of their new prime time shows that year.[78] This resulted in the signing of historic diversity agreements with ABC, CBS, Fox, and NBC that have since increased the hiring of Hispanic and Latino talent and other staff in all of the networks.

Latino Public Broadcasting (LPB) funds programs of educational and cultural significance to Hispanic Americans. These programs are distributed to various public television stations throughout the United States.

-

Robert Rodríguez is an American film director, screenwriter, producer, cinematographer, editor and musician.

-

Carolina Herrera, Venezuelan American fashion designer. Her designs have dressed numerous American First Ladies.

-

Anita Page, who is of Salvadoran ancestry, was referred to as "the girl with the most beautiful face in Hollywood" in the 1920s.

-

In 2010, Forbes ranked Cameron Diaz as the richest Hispanic female celebrity, ranking number 60 among the top 100.[79][80]

-

Óscar de la Renta, Dominican American fashion designer.

-

Luis Walter Álvarez, experimental physicist, inventor, and professor. Awarded the Nobel Prize of Physics in 1968.

Business and finance

The total number of Hispanic-owned businesses in 2002 was 1.6 million, having grown at triple the national rate for the preceding five years.[59]

Hispanic and Latino business leaders include Cuban immigrant Roberto Goizueta, who rose to head of The Coca-Cola Company.[82] Advertising magnate Arte Moreno became the first Hispanic to own a major league team in the United States when he purchased the Los Angeles Angels baseball club.[83] Also a major sports team owner is Linda G. Alvarado, president and CEO of Alvarado Construction, Inc and co-owner of the Colorado Rockies baseball team.

The largest Hispanic-owned food company in the US is Goya Foods, because of World War II hero Joseph A. Unanue, the son of the company's founders.[84] Angel Ramos was the founder of Telemundo, Puerto Rico's first television station[85] and now the second largest Spanish-language television network in the United States, with an average viewership over one million in primetime. Samuel A. Ramirez, Sr. made Wall Street history by becoming the first Hispanic to launch a successful investment banking firm, Ramirez & Co.[86][87] Nina Tassler is president of CBS Entertainment since September 2004. She is the highest-profile Latina in network television and one of the few executives who has the power to approve the airing or renewal of series.

Fashion

In the world of fashion, notable Hispanic and Latino designers include Oscar de la Renta, Carolina Herrera, and Narciso Rodríguez among others. Christy Turlington and Lea T achieved international fame as models.

Government and politics

As of 2007 there were more than five thousand elected officeholders in the United States who were of Latino origin.[88]

In the House of Representatives, Hispanic and Latino representatives have included Ladislas Lazaro, Antonio M. Fernández, Henry B. Gonzalez, Kika de la Garza, Herman Badillo, Romualdo Pacheco, and Manuel Lujan, Jr., out of almost two dozen former Representatives. Current Representatives include Luis Gutiérrez, Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, Nydia Velázquez, Joe Baca, Loretta Sanchez, Silvestre Reyes, Rubén Hinojosa, Linda Sánchez, and John Salazar—in all, they number twenty-three. Former senators are Octaviano Ambrosio Larrazolo, Mel Martinez, Dennis Chavez, Joseph Montoya, and Ken Salazar. As of January 2011, the U.S. Senate includes Hispanic members Bob Menendez, a Democrat, and Marco Rubio, a Republican.[89]

Numerous Hispanics and Latinos hold elective and appointed office in state and local government throughout the United States.[90] Current Hispanic Governors include Republican Nevada Governor Brian Sandoval and Republican New Mexico Governor Susana Martinez; upon taking office in 2011, Martinez became the first Latina governor in the history of the United States.[91] Former Hispanic governors include Democrats Jerry Apodaca, Raul Hector Castro, and Bill Richardson, as well as Republicans Octaviano Ambrosio Larrazolo, Romualdo Pacheco, and Bob Martinez.

Since 1988,[92] when Ronald Reagan appointed Lauro Cavazos the Secretary of Education, the first Hispanic United States Cabinet member, Hispanic Americans have had an increasing presence in presidential administrations. Hispanics serving in subsequent cabinets include Ken Salazar, current Secretary of the Interior; Hilda Solis, current United States Secretary of Labor; Alberto Gonzales, former United States Attorney General; Carlos Gutierrez, Secretary of Commerce; Federico Peña, former Secretary of Energy; Henry Cisneros, former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development; Manuel Lujan, Jr., former Secretary of the Interior; and Bill Richardson, former Secretary of Energy and Ambassador to the United Nations. Six of the last ten US Treasurers, including the latest three, are Hispanic women.

In 2009, Sonia Sotomayor became the first Supreme Court Associate Justice of Hispanic or Latino origin.

The Congressional Hispanic Caucus (CHC), founded in December 1976, and the Congressional Hispanic Conference (CHC), founded on March 19, 2003, are two organizations that promote policy of importance to Americans of Hispanic descent. They are divided into the two major American political parties: The Congressional Hispanic Caucus is composed entirely of Democratic representatives, whereas the Congressional Hispanic Conference is composed entirely of Republican representatives.

Literature and journalism

Among the distinguished Hispanic and Latino authors and their works may be noted:

- Isabel Allende (The House of the Spirits and City of the Beasts)

- Sandra Cisneros (The House on Mango Street and Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories)

- Julia Alvarez ("How the García Girls Lost Their Accents")

- Jorge Majfud Crisis

- Rudolfo Anaya (Bless Me, Ultima and Heart of Aztlan)

- Giannina Braschi (Empire of Dreams, Yo-Yo Boing!, and United States of Banana)

- Junot Díaz (The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao)

- Frank X Gaspar (Leaving Pico)

- Rigoberto González (Butterfly Boy: Memories of a Chicano Mariposa)

- Jovita González de Mireles (Caballero, cowritten with Eve Raleigh, and Dew On The Thorn)

- Oscar Hijuelos (The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love)

- Micol Ostow ("Mind Your Manners, Dick and Jane", "Emily Goldberg Learns to Salsa")[93]

- Benito Pastoriza Iyodo (A Matter of Men and September Elegies)

- Tomas Rivera (...And the Earth did Not Devour Him)

- Richard Rodriguez (Hunger of Memory)

- Rubén Salazar (journalist)

- George Santayana (novelist and philosopher: "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it")

- Sergio Troncoso (From This Wicked Patch of Dust and The Last Tortilla and Other Stories)

- Alisa Valdes-Rodriguez (Haters)

- Victor Villaseñor (Rain of Gold)

- Oscar Zeta Acosta (The Revolt of the Cockroach People)

- Guadalupe Baca-Vaughn (The Souls in Purgatory)

Military

Hispanics and Latinos have participated in the military of the United States and in every major military conflict from the American Revolution onward.[94] Tens of thousands of Latinos are deployed in the Iraq War, the Afghanistan War, and U.S. military missions and bases elsewhere. Hispanics and Latinos have not only distinguished themselves in the battlefields but also reached the high echelons of the military, serving their country in sensitive leadership positions on domestic and foreign posts. Up to now, 43 Hispanics and Latinos have been awarded the nation's highest military distinction, the Medal of Honor (also known as the Congressional Medal of Honor). The following is a list of some notable Hispanics/Latinos in the military:

- American Revolution

- Lieutenant Jorge Farragut Mesquida (1755–1817)-Participated in the American Revolution as a lieutenant in the South Carolina Navy.

- American Civil War

- Admiral David Farragut- Farragut was promoted to vice admiral on December 21, 1864, and to full admiral on July 25, 1866, after the war, thereby becoming the first person to be named full admiral in the Navy's history.[95]

- Colonel Ambrosio José Gonzales – Gonzales was active during the bombardment of Fort Sumter and because of his actions was appointed Colonel of artillery and assigned to duty as Chief of Artillery in the department of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida.

- Brigadier General Diego Archuleta (1814–1884) – was a member of the Mexican Army who fought against the United States in the Mexican American War. During the American Civil War he joined the Union Army (US Army) and became the first Hispanic to reach the military rank of Brigadier General. He commanded The First New Mexico Volunteer Infantry in the Battle of Valverde. He was later appointed an Indian (Native Americans) Agent by Abraham Lincoln.[96]

- Colonel Carlos de la Mesa – Grandfather of Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen, Sr. commanding general of the First Infantry Division in North Africa and Sicily, and later the commander of the 104th Infantry Division during World War II. Colonel Carlos de la Mesa was a Spanish national who fought at Gettysburg for the Union Army in the Spanish Company of the "Garibaldi Guard" of the 39th New York State Volunteers.[97]

- Colonel Federico Fernández Cavada – Commanded the 114th Pennsylvania Volunteer infantry regiment when it took the field in the Peach Orchard at Gettysburg.[98]

- Colonel Miguel E. Pino – Commanded the 2nd Regiment of New Mexico Volunteers, which fought at the Battle of Valverde in February and the Battle of Glorieta Pass and helped defeat the attempted invasion of New Mexico by the Confederate Army.[99]

- Colonel Santos Benavides – Commanded his own regiment, the "Benavides Regiment." He was the highest ranking Mexican-American in the Confederate Army.[98]

- Major Salvador Vallejo – Officer in one of the California units that served with the Union Army in the West.[99]

- Captain Adolfo Fernández Cavada – Cavada served in the 114th Pennsylvania Volunteers at Gettysburg with his brother, Colonel Federico Fernandez Cavada. He served with distinction in the Army of the Potomac from Fredericksburg to Gettysburg and was a "special aide-de-camp" to General Andrew A. Humphreys.[98][100]

- Captain Roman Anthony Baca – Member of the Union forces in the New Mexico Volunteers. He also served as a spy for the Union Army in Texas.[99]

- Lieutenant Augusto Rodriguez – A Puerto Rican native who served as an officer in the 15th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, of the Union Army. Rodríguez served in the defenses of Washington, D.C. and led his men in the Battles of Fredericksburg and Wyse Fork.[101]

- Lola Sánchez – Sánchez was a Cuban born woman who became a Confederate spy who helped the Confederates obtain a victory against the Union Forces in the "Battle of Horse Landing".

- Loreta Janeta Velazquez as known as "Lieutenant Harry Buford" – She was a Cuban woman who donned Confederate garb and served as a Confederate officer and spy during the American Civil War.

- World War I

- Major General Luis R. Esteves, U.S. Army- In 1915, Esteves became the first Hispanic to graduate from the United States Military Academy ("West Point"). Esteves also organized the Puerto Rican National Guard.

- First Lieutenant Félix Rigau Carrera, known as "El Aguila de Sabana Grande" (The Eagle from Sabana Grande)-Was the first Hispanic fighter pilot in the United States Marine Corps.[102]

- Private Marcelino Serna- Was an undocumented Mexican immigrant who joined the United States Army and became the most decorated soldier from Texas in World War I. Serna was the first Hispanic to be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

- World War II

- Lieutenant General Pedro del Valle – the first Hispanic to reach the rank of Lieutenant General. He played an instrumental role in the seizure of Guadalcanal and Okinawa as Commanding General of the U.S. 1st Marine Division during World War II.

- Lieutenant General Elwood R. Quesada (1904–1993) – Commanding general of the 9th Fighter Command, where he established advanced headquarters on the Normandy beachhead on D-Day plus one, and directed his planes in aerial cover and air support for the Allied invasion of the European continent during World War II. He was the foremost proponent of "the inherent flexibility of air power", a principle he helped prove during the war.

- Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen, Sr. (1888–1969) – was the commanding general of the 1st Infantry Division in North Africa and Sicily during World War II, and was made commander of the 104th Infantry Division.

- Colonel Virgil R. Miller – was the Regimental Commander of the 442d Regimental Combat Team, a unit that was composed of "Nisei" (second generation Americans of Japanese descent), during World War II. He led the 442nd in its rescue of the Lost Texas Battalion of the 36th Infantry Division, in the forests of the Vosges Mountains in northeastern France.[103][104]

- Captain Marion Frederic Ramírez de Arellano (1913–1980) – served in World War II and was the first Hispanic submarine commander.

- First Lieutenant Oscar Francis Perdomo, of the 464th Fighter Squadron, 507th Fighter Group was the last "Ace in a Day" for the United States in World War II.

- CWO2 Joseph B. Aviles, Sr. – a member of the United States Coast Guard and the first Hispanic-American to be promoted to Chief Petty Officer, received a war-time promotion to Chief Warrant Officer (November 27, 1944), thus becoming the first Hispanic American to reach that level as well.[105]

- Sergeant First Class Agustín Ramos Calero – was the most decorated Hispanic soldier in the European Theatre of World War II.

- PFC Guy Gabaldon, USMC – captured over a thousand prisoners during the World War II Battle of Saipan.

- Tech4 Carmen Contreras-Bozak – the first Hispanic to serve in the U.S. Women's Army Corps where she served as an interpreter and in numerous administrative positions.[106]

- Korean War

- Major General Salvador E. Felices, U.S. Air Force – In 1953, Felices flew in 19 combat missions over North Korea, during the Korean War. In 1957, he participated in "Operation Power Flite", a historic project that was given to the Fifteenth Air Force by the Strategic Air Command headquarters. Operation Power Flite was the first around the world non-stop flight by an all-jet aircraft.

- First Lieutenant Baldomero Lopez – is the only Hispanic graduate of the United States Naval Academy ("Annapolis") to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

- Sergeant First Class Modesto Cartagena- was a member of the 65th Infantry Regiment, an all-Puerto Rican regiment also known as "The Borinqueneers", during World War II and the Korean War. He was the most decorated Puerto Rican soldier in history.[107]

- Cuban Missile Crisis

- Admiral Horacio Rivero, Jr.- second Hispanic four-star Admiral, was the commander of the American fleet sent by President John F. Kennedy to set up a quarantine (blockade) of the Soviet ships during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

- Vietnam War

- Sergeant First Class Jorge Otero Barreto a.k.a. "The Puerto Rican Rambo"- was the most decorated Hispanic American soldier in the Vietnam War[108]

- Post-Vietnam

- Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez- top commander of the Coalition forces during the first year of the occupation of Iraq, 2003–2004, during the Iraq War

- Lieutenant General Edward D. Baca- In 1994, Baca became the first Hispanic Chief of the National Guard Bureau.

- Vice Admiral Antonia Novello, M.D., Public Health Service Commissioned Corps- In 1990, Novello became the first Hispanic (and first female) U.S. Surgeon General.

- Vice Admiral Richard Carmona, M.D., Public Health Service Commissioned Corps- Carmona served as the 17th Surgeon General of the United States, under President George W. Bush.

- Brigadier General Joseph V. Medina, USMC -made history by becoming the first Marine Corps officer to take command of a Naval flotilla.

- Rear Admiral Ronald J. Rábago is the first person of Hispanic American descent to be promoted to Rear Admiral (lower half) in the United States Coast Guard.[109]

- Captain Linda Garcia Cubero, United States Air Force- in 1980 became the first Hispanic woman graduate of the United States Air Force.

- Major General Erneido Oliva. He was appointed to the position of Deputy Commanding General of the D.C. National Guard.

- Brigadier General Carmelita Vigil-Schimmenti, United States Air Force- in 1985 became the first Hispanic female to attain the rank of Brigadier General in the Air Force.[110][111]

- On August 2, 2006, Brigadier General Angela Salinas, made history when she became the first Hispanic female to obtain a general rank in the Marines.[112]

- Chief Master Sergeant Ramón Colón-López is pararescueman who in 2007, was the only Hispanic among the first six airmen to be awarded the newly created Air Force Combat Action Medal.

Medal of Honor

The following 43 Hispanics were awarded the Medal of Honor:

Philip Bazaar, Joseph H. De Castro, John Ortega, France Silva, David B. Barkley, Lucian Adams, Rudolph B. Davila, Marcario Garcia, Harold Gonsalves, David M. Gonzales, Silvestre S. Herrera, Jose M. Lopez, Joe P. Martinez, Manuel Perez Jr., Cleto L. Rodriguez, Alejandro R. Ruiz, Jose F. Valdez, Ysmael R. Villegas, Fernando Luis García, Edward Gomez, Ambrosio Guillen, Rodolfo P. Hernandez, Baldomero Lopez, Benito Martinez, Eugene Arnold Obregon, Joseph C. Rodriguez, John P. Baca, Roy P. Benavidez, Emilio A. De La Garza, Ralph E. Dias, Daniel Fernandez, Alfredo Cantu "Freddy" Gonzalez, Jose Francisco Jimenez, Miguel Keith, Carlos James Lozada, Alfred V. Rascon, Louis R. Rocco, Euripides Rubio, Hector Santiago-Colon, Elmelindo Rodrigues Smith, Jay R. Vargas, Humbert Roque Versace, and Maximo Yabes.

National intelligence

- In the spy arena, José Rodríguez, a native of Puerto Rico, was the Deputy Director of Operations and subsequently Director of the National Clandestine Service (D/NCS), two senior positions in the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), between 2004 and 2007.[113]

- Lieutenant Colonel Mercedes O. Cubria (1903–1980), a.k.a. La Tía (The Aunt), was the first Cuban-born female officer in the U.S. Army. She served in the Women's Army Corps during World War II, in the U.S. Army during the Korean War, and was recalled into service during the Cuban Missile Crisis. In 1988, she was posthumously inducted into the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame.[114]

Science and technology

Among Hispanic Americans who have excelled in science are Luis Walter Álvarez, Nobel Prize–winning physicist, and his son Walter Alvarez, a geologist. They first proposed that an asteroid impact on the Yucatán Peninsula caused the extinction of the dinosaurs. Dr. Victor Manuel Blanco is an astronomer who in 1959 discovered "Blanco 1", a galactic cluster.[116] F. J. Duarte is a laser physicist and author; he received the Engineering Excellence Award from the prestigious Optical Society of America for the invention of the N-slit laser interferometer.[117] Francisco J. Ayala is a biologist and philosopher, former president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and has been awarded the National Medal of Science and the Templeton Prize.

Dr. Fernando E. Rodríguez Vargas discovered the bacteria that cause dental cavity. Dr. Gualberto Ruaño is a biotechnology pioneer in the field of personalized medicine and the inventor of molecular diagnostic systems, Coupled Amplification and Sequencing (CAS) System, used worldwide for the management of viral diseases.[118] Fermín Tangüis was an agriculturist and scientist who developed the Tangüis Cotton in Peru and saved that nation's cotton industry.[119] Severo Ochoa, born in Spain, was a co-winner of the 1959 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Some Hispanics and Latinos have made their names in astronautics, including several NASA astronauts:[120] Franklin Chang-Diaz, the first Latin American NASA astronaut, is co-recordholder for the most flights in outer space, and is the leading researcher on the plasma engine for rockets; France A. Córdova, former NASA chief scientist; Juan R. Cruz, NASA aerospace engineer; Lieutenant Carlos I. Noriega, NASA mission specialist and computer scientist; Dr. Orlando Figueroa, mechanical engineer and Director of Mars Exploration in NASA; Amri Hernández-Pellerano, engineer who designs, builds and tests the electronics that will regulate the solar array power in order to charge the spacecraft battery and distribute power to the different loads or users inside various spacecraft at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

Mercedes Reaves, research engineer and scientist who is responsible for the design of a viable full-scale solar sail and the development and testing of a scale model solar sail at NASA Langley Research Center. Dr. Pedro Rodríguez, inventor and mechanical engineer who is the director of a test laboratory at NASA and of a portable, battery-operated lift seat for people suffering from knee arthritis. Dr. Felix Soto Toro, electrical engineer and astronaut applicant who developed the Advanced Payload Transfer Measurement System (ASPTMS) (Electronic 3D measuring system); Ellen Ochoa, a pioneer of spacecraft technology and astronaut; Joseph Acaba, Fernando Caldeiro, Sidney Gutierrez, Jose Hernández, Michael López-Alegría, John Olivas, and George Zamka, who are current or former astronauts.

Sports

Baseball

The large number of Hispanic and Latino American stars in Major League Baseball (MLB) includes players like Ted Williams (considered by many to be the greatest hitter of all time), Miguel Cabrera, Lefty Gómez, Iván Rodríguez, Carlos González, Roberto Clemente, Adrian Gonzalez, David Ortiz, Fernando Valenzuela, Nomar Garciaparra, Albert Pujols, Omar Vizquel, managers Al López, Ozzie Guillén, and Felipe Alou, and General Manager Omar Minaya.

Basketball and football

There have been far fewer football and basketball players, let alone star players, but Tom Flores was the first Hispanic head coach and the first Hispanic quarterback in American professional football, and won Super Bowls as a player, as assistant coach and as head coach for the Oakland Raiders. Anthony Múñoz is enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, ranked #17 on Sporting News's 1999 list of the 100 greatest football players, and was the highest-ranked offensive lineman. Jim Plunkett won the Heisman Trophy and was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame, and Joe Kapp is inducted into the Canadian Football Hall of Fame and College Football Hall of Fame. Steve Van Buren, Martin Gramatica, Victor Cruz, Tony Gonzalez, Marc Bulger, Tony Romo and Mark Sanchez can also be cited among successful Hispanics and Latinos in the National Football League (NFL).

Trevor Ariza, Mark Aguirre, Carmelo Anthony, Manu Ginobili, Carlos Arroyo, Gilbert Arenas, Rolando Blackman, Pau Gasol, Jose Calderon, José Juan Barea and Charlie Villanueva can be cited in the National Basketball Association (NBA). Dick Versace made history when he became the first person of Hispanic heritage to coach an NBA team. Rebecca Lobo was a major star and champion of collegiate (National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA)) and Olympic basketball and played professionally in the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA). Diana Taurasi became just the seventh player ever to win an NCAA title, a WNBA title, and as well an Olympic gold medal. Orlando Antigua became in 1995 the first Hispanic and the first non-black in 52 years to play for the Harlem Globetrotters.

Tennis

Tennis legend Pancho Gonzales and Olympic tennis champions and professional players Mary Joe Fernández and Gigi Fernández; soccer players in the Major League Soccer (MLS) Tab Ramos, Claudio Reyna, Marcelo Balboa and Carlos Bocanegra; figure skater Rudy Galindo; golfers Chi Chi Rodríguez, Nancy López, and Lee Trevino; softball player Lisa Fernández; and Paul Rodríguez Jr., X Games professional skateboarder, are all Hispanic or Latino Americans who have distinguished themselves in their sports.

Other sports

Boxing's first Hispanic world champion was Panama Al Brown. Some other champions include Oscar De La Hoya, Miguel Cotto, Bobby Chacon, Joel Casamayor, Michael Carbajal, John Ruiz, and Carlos Ortiz.

Ricco Rodriguez, Tito Ortiz, Diego Sanchez, Nick Diaz, Nathan Diaz' Dominick Cruz, Frank Shamrock, Gilbert Melendez, Roger Huerta, Carlos Condit, Kelvin Gastelum, and UFC Heavy Weight Champion Cain Velasquez have been competitors in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) of mixed martial arts.

In 1991 Bill Guerin whose mother is Nicaraguan became the first Hispanic player in the National Hockey League (NHL). He was also selected to four NHL All-Star Games. In 1999 Scott Gomez won the NHL Rookie of the Year Award.[121]

In sports entertainment we find the professional wrestlers Alberto Del Rio, Rey Mysterio, Eddie Guerrero, Tyler Black and Melina Pérez, and executive Vickie Guerrero.

Socioeconomics

Education

| Ethnicity or nationality | Percent of Population | |

|---|---|---|

| Venezuelan | 50% | |

| Argentinean | 39% | |

| Chilean | 36% | |

| Bolivian | 34% | |

| Colombian | 31% | |

| Panamanian | 31% | |

| Peruvian | 31% | |

| Spaniard | 30% | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 30% | |

| Cuban | 25% | |

| Costa Rican | 25% | |

| General Hispanic population | 13% | |

| General US population | 28% | |

| Sources:[123] | ||

In terms of educational attainment, Hispanic and Latino Americans of South American descent have the highest college graduation rates, and significantly higher than the national average. In 2013, Hispanic high school graduates passed Non-Hispanic Whites in rate of college enrollment. 69% of Hispanic high school graduates enroll in a university immediately after graduation.[124]

Those with a bachelors degree or higher ranges from 50% of Venezuelans compared to 18% for Ecuadorians 25 years and older. Amongst the largest Hispanic groups, those with a bachelors or higher was 25% for Cuban Americans, 16% of Puerto Ricans, 15% of Dominicans, and 9% for Mexican Americans. Over 21% of all second-generation Dominican Americans have college degrees, slightly below the national average (28%) but significantly higher than U.S.-born Mexican Americans (13%) and U.S.-born Puerto Rican Americans (12%).[125]

Hispanic and Latinos make up the second or third largest ethnic group in Ivy League universities, considered to be the most prestigious in the United States. Hispanic and Latino enrollment at Ivy League universities has gradually increased over the years. Today, Hispanics make up between 8% of students at Yale University to 15% at Columbia University.[126] For example, 18% of students in the Harvard University Class of 2018 are Hispanic.[127]

Hispanics have significant enrollment in many other top universities such as Florida International University (63% of students), University of Miami (27%), and MIT, UCLA, & UC-Berkeley at 15% each. At Stanford University, Hispanics are the second largest ethnic group behind Non-Hispanic Whites, at 18% of the student population.[128]

In the 2010 US Census, the high school graduation rate for Hispanics was 62% overall. It is highest among Cuban Americans (69%) and lowest among Mexican Americans (48%). The Puerto Rican rate is 63%, Central and South American Americans is 60%, and Dominican Americans is 52%.

Health

Hispanic and Latino Americans are the longest-living Americans, according to official data. Their life expectancy is more than two years longer than for non-Hispanic whites and almost eight years longer than for African Americans.[129]

Workforce and average income

In 2002, the average individual income among Hispanic and Latino Americans was highest for Cuban Americans ($38,733), and lowest for Dominican Americans ($26,467) and Puerto Ricans ($27,877). For Mexican Americans, it was $33,927, and $30,444 for Central and South Americans. In comparison, the income of the average Hispanic American is lower than the national average.

Among Hispanics, Cuban Americans (28.5 percent) had the highest percentage in professional–managerial occupations. The percentage for Mexican Americans was 20.7, Central and South Americans' was 8.8 percent, and Puerto Ricans was 7.2 percent. All these are lower than the average for non-Hispanics (36.2 percent).[citation needed]

Poverty

According to the ACS, the poverty rate among Hispanic groups is highest among Dominican Americans (28.1 percent), Mexican Americans (23.9 percent), and Honduran Americans and Puerto Ricans (23.7 percent both). It is lowest among South Americans, such as Colombian Americans (10.6 percent) and Peruvian Americans (13.6 percent), and relatively low poverty rates are also found among Salvadoran Americans (15.0 percent) and Cuban Americans (15.2 percent).[131]

In comparison, the average poverty rates for non-Hispanic White Americans (8.8 percent)[131] and Asian Americans (7.1 percent) were lower than those of any Hispanic group. African Americans (21.3 percent) had a higher poverty rate than Cuban Americans and Central and South Americans, but had a lower poverty rate than Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Dominican Americans.[131]

Cultural influence

The geographic, political, social, economic, and racial other diversity of Hispanic and Latino Americans extends to culture, as well. Yet several features tend to unite Hispanics and Latinos from these diverse backgrounds.

| Year | Number of Spanish speakers | Percent of US population |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 11 million | 5% |

| 1990 | 17.3 million | 7% |

| 2000 | 28.1 million | 10% |

| 2010 | 37 million | 13% |

| 2020 (projected) | 40 million | 14% |

| Sources:[132][133][134][135] | ||

Language

Hispanics have revived the Spanish language in the United States. First brought to North America by the Spanish during the Spanish colonial period in the 16th century, Spanish was the first European language spoken in the Americas. Spanish is the oldest European language in the United States, spoken uninterruptedly for four and a half centuries, since the foundation of St. Augustine.[36][37][38][39] Today, 90% of all Hispanic and Latinos speak English, and at least 78% speak Spanish.[138]

With 40% of Hispanic and Latino Americans being immigrants,[139] and with many of the 60% who are U.S.-born being the children or grandchildren of immigrants, bilingualism is the norm in the community at large: at home, at least 69% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans over age five are bilingual in English and Spanish, whereas up to 22% are monolingual English-speakers, and 9% are monolingual Spanish-speakers; another 0.4% speak a language other than English and Spanish at home.[138]

The usual pattern is monolingual Spanish use among new migrants or older foreign-born Hispanics, complete bilingualism among long-settled immigrants and the children of immigrants, and the sole use of English, or both English and either Spanglish or colloquial Spanish by the third generation and beyond.

Religion

The most methodologically rigorous study of Hispanic or Latino religious affiliation to date was the Hispanic Churches in American Public Life (HCAPL) National Survey, conducted between August and October 2000. This survey found that 70% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans are Catholic, 20% are Protestant, 3% are "alternative Christians" (such as Mormon or Jehovah's Witnesses), 1% identify with a non-Christian religion (including Muslims), and 6% have no religious preference (with only 0.37% claiming to be atheist or agnostic). This suggests that Hispanics/Latinos are not only a highly religious, but also a highly Christian constituency.

It also suggests that Hispanic/Latino Protestants are a more sizable minority than sometimes realized. Catholic affiliation is much higher among first-generation than second- or third-generation Hispanic or Latino immigrants, who exhibit a fairly high rate of defection to Protestantism.[140] Also Hispanics and Latinos in the Bible Belt, which is mostly located in the South, are more likely to defect to Protestantism than those in other regions. Examples of Protestant denominations that experiencing an inflow of Hispanic/Latino converts are Pentecostalism[141][142] and the Episcopal Church.[143][144] Hispanic or Latino Catholics are also increasingly working to enhance member retention through youth and social programs and through the spread of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal.[145]

Media

The United States is home to thousands of Spanish-language media outlets, which range in size from giant commercial and some non-commercial broadcasting networks and major magazines with circulations numbering in the millions, to low-power AM radio stations with listeners numbering in the hundreds. There are hundreds of Internet media outlets targeting U.S. Hispanic consumers. Some of the outlets are online versions of their printed counterparts and some online exclusively.

Among the most noteworthy Hispanic/Latino-oriented media outlets are:

- Univisión, the largest Spanish-language television network[disambiguation needed] in the United States, with affiliates in nearly every major U.S. market, and numerous affiliates internationally;

- Telemundo, the second-largest Spanish-language television network in the United States, with affiliates in nearly every major U.S. market, and numerous affiliates internationally;

- Azteca América, a Spanish-language television network in the United States, with affiliates in nearly every major U.S. market, and numerous affiliates internationally;

- La Opinión, a Spanish-language daily newspaper published in Los Angeles, California and distributed throughout the six counties of Southern California. It is the largest Spanish-language newspaper in the United States;

- El Nuevo Herald and Diario Las Américas, both Spanish-language daily newspapers serving the greater Miami, Florida market;

- La Voz de Indiana, a bilingual (English and Spanish) publication based in Indianapolis, Indiana;

- Hispanic Business, an English-language business magazine about Hispanics;

- mun2, a cable network that produces content for U.S.-born Hispanic and Latino audiences;

- People en Español, a Spanish-language magazine counterpart of People;

- ConSentido TV, a television, radio, and newspaper network in North Texas;

- TBN Enlace USA, a Spanish-language Christian television network based in Tustin, California;

- 3ABN Latino, a Spanish-language Christian television network based in West Frankfort, Illinois;

- CNN en Español, a Spanish-language all-news television network based in Atlanta, Georgia;

- Vida Latina, a Spanish-language entertainment magazine distributed throughout the Southern United States.

- ESPN Deportes and Fox Deportes, two Spanish-language sports television networks.

Cuisine

Hispanics, particularly Cuban, Mexican, and Puerto Ricans, have influenced American cuisine and American eating habits. Mexican cuisine is now popular across the US, making tortillas and salsa more popular than hamburger buns and ketchup. Tortilla chips have also surpassed potato chips in annual sales, and plantain chips popular in Caribbean cuisines has continued to grow in popularity.[147]

Due to the large Mexican American population in the Southwestern United States, and its proximity to Mexico, Mexican food there is believed to be some of the best in the US. Cubans brought Cuban cuisine to Miami, and today, cortaditos, pastelitos de guayaba, and empanadas are common mid-day snacks. Cuban culture has changed Miami's coffee drinking habits, and today a café con leche or a cortadito is commonly had, often with a pastelito (pastry) at one of the city's numerous coffee shops.[148] The Cuban sandwich was invented in Miami, and is now also a staple and icon of the city's cuisine and culture.[149]

Intermarriage

Hispanic Americans, like immigrant groups before them, are out-marrying at high rates. Out-marriages comprise 17.4% of all existing Hispanic marriages in 2008.,[150] and the rate is higher for newlyweds (which excludes immigrants who are already married): Among all newlyweds in 2010, 25.7% of all Hispanics married a non-Hispanic (this compares to out-marriage rates of 9.4% of whites, 17.1% of blacks, and 27.7% of Asians). The rate was larger for native-born Hispanics, with 36.2% of native-born Hispanics (both men and women) out-marrying compared to 14.2% of foreign-born Hispanics.[151] The difference is attributed to recent immigrants tending to marry within their immediate immigrant community due to commonality of language, proximity, familial connections, and familiarity.[150]

In 2008, 81% of Hispanics who intermarried married non-Hispanic Whites, 9% married non-Hispanic Blacks, 5% non-Hispanic Asians, and the remainder married non-Hispanic, multi-racial partners.[150]

Of the 275,500 new intermarried pairings in 2010, 43.3% were White-Hispanic (compared to White-Asian at 14.4%, White-Black at 11.9%, and Other Combinations at 30.4%; other combinations consists of pairings between different minority groups, multi-racial people, and American Indians).[151] Unlike blacks and Asians, intermarriage rates between White and Hispanic newlyweds do not vary by gender. The combined median earnings of White/Hispanic couples are lower than those of White/White couples but higher than those of Hispanic/Hispanic couples. 23% of Hispanic men who married White women have a college degree compared to only 10% of Hispanic men who married a Hispanic woman. 33% of Hispanic women who married a White husband are college-educated compared to 13% of Hispanic women who married a Hispanic man.[151]

Attitudes amongst non-Hispanics toward intermarriage with Hispanics are mostly favorable with 81% of Whites, 76% of Asians, and 73% of Blacks "being fine" with a member of their family marrying a Hispanic and an additional 13% of Whites, 19% of Asians, and 16% of Blacks "being bothered but accepting of the marriage." Only 2% of Whites, 4% of Asians, and 5% of Blacks would not accept a marriage of their family member to a Hispanic.[150]

Hispanic attitudes toward intermarriage with non-Hispanics are likewise favorable with 71% "being fine" with marriages to Whites and 81% "being fine" with marriages to Blacks. A further 22% admitted to "being bothered but accepting" of a marriage of a family member to a White and 16% admitted to "being bothered but accepting" of a marriage of a family member to a Black. Only 3% of Hispanics objected outright marriage of a family member to a non-Hispanic Black and 3% to a non-Hispanic White.[150]

Political trends

Hispanics and Latinos differ on their political views depending on their location and background, but the majority (57%)[152] either identify themselves as or support the Democrats, and 23% identify themselves as Republicans.[152] This 34 point gap as of December 2007 was an increase from the gap of 21 points 16 months earlier. Cuban Americans and Colombian Americans tend to favor conservative political ideologies and support the Republicans, while Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Dominican Americans tend to favor liberal views and support the Democrats. However, because the latter groups are far more numerous—as, again, Mexican Americans alone are 64% of Hispanics and Latinos—the Democratic Party is considered to be in a far stronger position with the group overall.

The Presidency of George W. Bush had a significant impact on the political leanings of Hispanics and Latinos. As a former Governor of Texas, Bush regarded this growing community as a potential source of growth for the conservative movement and the Republican Party,[citation needed] and he made some gains for the Republicans among the group.

In the 1996 presidential election, 72% of Hispanics and Latinos backed President Bill Clinton, but in 2000 the Democratic total fell to 62%, and went down again in 2004, with Democrat John Kerry winning Hispanics 58–40 against Bush.[153] Hispanics in the West, especially in California, were much stronger for the Democratic Party than in Texas and Florida. California Latinos voted 63–32 for Kerry in 2004, and both Arizona and New Mexico Latinos by a smaller 56–43 margin; but Texas Latinos were split nearly evenly, favoring Kerry 50–49, and Florida Latinos (mostly being Cuban American) backed Bush, by a 54–45 margin.

In the 2006 midterm election, however, due to the unpopularity of the Iraq War, the heated debate concerning illegal immigration, and Republican-related Congressional scandals, Hispanics and Latinos went as strongly Democratic as they have since the Clinton years. Exit polls showed the group voting for Democrats by a lopsided 69–30 margin, with Florida Latinos for the first time split evenly. The runoff election in Texas' 23rd congressional district was seen as a bellwether of Latino politics, and Democrat Ciro Rodriguez's unexpected (and unexpectedly decisive) defeat of Republican incumbent Henry Bonilla was seen as proof of a leftward lurch among Latino voters, as heavily Latino counties overwhelmingly backed Rodriguez, and heavily Anglo counties overwhelmingly backed Bonilla.

Although during 2008 the economy and employment were top concerns for Hispanics and Latinos, immigration was "never far from their minds": almost 90% of Latino voters rated immigration as "somewhat important" or "very important" in a poll taken after the election.[154] There is "abundant evidence" that the heated Republican opposition to the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007 has done significant damage to the party's appeal to Hispanics and Latinos in the years to come, especially in the swing states such as Florida, Nevada, and New Mexico.[154] In a Gallup poll of 4,604 registered Hispanic voters taken in the final days of June 2008, only 18% of participants identified themselves as Republicans.[155]

2008 election

In the 2008 Presidential election's Democratic primary Hispanics and Latinos participated in larger numbers than before, with Hillary Clinton receiving most of the group's support.[156] Pundits discussed whether a large percentage of Hispanics and Latinos would vote for an African American candidate, in this case Barack Obama, Clinton's opponent.[157] Hispanics/Latinos voted 2 to 1 for Mrs. Clinton, even among the younger demographic, which in the case of other groups was an Obama stronghold.[158] Among Hispanics, 28% said race was involved in their decision, as opposed to 13% for (non-Hispanic) whites.[158]

Obama defeated Clinton. In the matchup between Obama and Republican candidate John McCain for the presidency, Hispanics and Latinos supported Obama with 59% to McCain's 29% in the Gallup tracking poll as of June 30, 2008.[155] This surprised some analysts, since a higher than expected percentage of Latinos and Hispanics favored Obama over McCain, who had been a leader of the comprehensive immigration reform effort.[159] However, McCain had retracted during the Republican primary, stating that he would not support the bill if it came up again. Some analysts believed that this move hurt his chances among Hispanics and Latinos.[160] Obama took advantage of the situation by running ads aimed at the ethnic group, in Spanish, in which he mentioned McCain's about-face.[161]

In the general election, 67% of Hispanics and Latinos voted for Obama[162] and 31% voted for McCain,[163] with a relatively stronger turnout than in previous elections in states such as Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, and Virginia helping Obama carry those formerly Republican states. Obama won 70% of non-Cuban Hispanics and 35% of the traditionally Republican Cuban Americans that have a strong presence in Florida, while the changing state demographics towards a more non-Cuban Hispanic community also contributed to his carrying Florida's Latinos with 57% of the vote.[162][164] Hispanics and Latinos also supplanted Republican gains in traditional red states, for example Obama carried 63% of Texas Latinos, despite that the overall state voted for McCain by 55%.[165]

Some political organizations associated with Hispanic and Latino Americans are LULAC, the NCLR, the United Farm Workers, the Cuban American National Foundation, and the National Institute for Latino Policy.

2012 election

Hispanic and Latinos went even more heavily for Democrats in the 2012 election with the Democratic incumbent Barack Obama receiving 71% and the Republican challenger Mitt Romney receiving about 27% of the vote.[166][167]

Cultural issues

Hispanophobia

Hispanophobia has existed in various degrees throughout U.S. history, based largely on ethnicity, race, culture, Anti-Catholicism, economic and social conditions in Latin America, and use of the Spanish language.[168][169][170][171] In 2006, Time Magazine reported that the number of hate groups in the United States increased by 33 percent since 2000, primarily due to anti-illegal immigrant and anti-Mexican sentiment.[172] According to Federal Bureau of Investigation statistics, the number of anti-Latino hate crimes increased by 35 percent since 2003 (albeit from a low level). In California, the state with the largest Latino population, the number of hate crimes against Latinos almost doubled.[173]

For the year 2009, the FBI reported that 483 of the 6,604 hate crimes committed in the United States were anti-Hispanic comprising 7.3% of all hate crimes. This compares to 34.6% of hate crimes being anti-Black, 17.9% being anti-Homosexual, 14.1% being anti-Jewish, and 8.3% being anti-White.[174]

Relations with other minority groups

As a result of the rapid growth of the Hispanic population, there has been some tension with other minority populations,[175] especially the African American population, as Hispanics have increasingly moved into once exclusively Black areas.[176][177][178][179][180][181][182][183][184][185][186] There has also been increasing cooperation between minority groups to work together to attain political influence.[187][188][189][190][191]

- A 2007 UCLA study reported that 51% of Blacks felt that Hispanics were taking jobs and political power from them and 44% of Hispanics said they feared African-Americans identifying them with high crime rates. That said, large majorities of Hispanics credited American blacks and the civil rights movement with making life easier for them in the US.[192][193]

- A Pew Research Center poll from 2006 showed that Blacks overwhelmingly felt that Hispanic immigrants were hard working (78%) and had strong family values (81%) but also that they believed that immigrants took jobs from Americans (34%) with a significant minority of Blacks (22%) believing that they had directly lost a job to an immigrant and 34% of Blacks wanting immigration to be curtailed. The report also surveyed three cities: Chicago (with its well-established Latino community); Washington DC (with a less-established but quickly growing Hispanic community); and Raleigh-Durham (with a very new but rapidly growing Hispanic community). The results showed that a significant proportion of Blacks in those cities wanted immigration to be curtailed: Chicago (46%), Raleigh-Durham (57%), and Washington DC (48%).[194]

- Per a 2008 University of California, Berkeley Law School research brief, a recurring theme to Black / Hispanic tensions is the growth in "contingent, flexible, or contractor labor," which is increasingly replacing long term steady employment for jobs on the lower-rung of the pay scale (which had been disproportionately filled by Blacks). The transition to this employment arrangement corresponds directly with the growth in the Latino immigrant population. The perception is that this new labor arrangement has driven down wages, removed benefits, and rendered temporary, jobs that once were stable (but also benefiting consumers who receive lower-cost services) while passing the costs of labor (healthcare and indirectly education) onto the community at large.[195]

- A 2008 Gallup poll indicated that 60% of Hispanics and 67% of blacks believe that good relations exist between US blacks and Hispanics[196] while only 29% of blacks, 36% of Hispanics, and 43% of whites, say Black–Hispanic relations are bad.[196]

- In 2009, in Los Angeles County, Latinos committed 77% of the hate crimes against black victims and blacks committed half of the hate crimes against Latinos.[197]

See also

Places of settlement in United States:

- List of U.S. communities with Hispanic majority populations in the 2010 census

- List of U.S. cities with large Hispanic population

- List of U.S. cities by Spanish-speaking population

- Hispanic and Latino Americans in California

- Hispanic and Latino Americans in Arizona

- Hispanic and Latino Americans in New Mexico

- Hispanic and Latino Americans in Texas

- Hispanic and Latino Americans in Nevada

- Hispanic and Latino Americans in Florida

- National Alliance for Hispanic Health

Diaspora:

Individuals:

- List of Hispanic and Latino Americans

General:

Footnotes

- ^ a b c U.S. Catholic Hispanic Population Less Religious, Shrinking

- ^ Growing number of Latinos have no religious affiliation

- ^ a b http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf

- ^ a b US Census Bureau 2012 American Community Survey B03001 1-Year Estimates HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY SPECIFIC ORIGIN retrieved September 20, 2013

- ^ Luis Fraga; John A. Garcia (2010). Latino Lives in America: Making It Home. Temple University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-4399-0050-5.

- ^ Nancy L. Fisher (1996). Cultural and Ethnic Diversity: A Guide for Genetics Professionals. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8018-5346-3.

- ^ Robert H. Holden; Rina Villars (2012). Contemporary Latin America: 1970 to the Present. John Wiley & Sons. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-118-27487-3.

- ^ a b "49 CFR Part 26". Retrieved 2012-10-22.

'Hispanic Americans,' which includes persons of Mexican-, Puerto Rican-, Cuban, Dominican-, Central or South American, or other Spanish, culture or origin, regardless of race;

- ^ a b "US Small Business Administration 8(a) Program Standard Operating Procedure" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-10-22.

SBA has defined 'Hispanic American' as an individual whose ancestry and culture are rooted in South America, Central America, Mexico, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, or the Iberian Peninsula, including Spain and Portugal.

- ^ Humes, Karen R.; Jones, Nicholas A.; Ramirez, Roberto R. "Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

"Hispanic or Latino" refers to a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American, or other Spanish or Portuguese culture or origin regardless of race.

- ^ "American FactFinder Help: Hispanic or Latino origin". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-10-05.