Geography of Tuvalu

| |

| Continent | Pacific Ocean |

|---|---|

| Region | Western Pacific |

| Coordinates | 5°41′S 176°12′E / 5.683°S 176.200°E |

| Area | Ranked 191st |

| • Total | 26.26 km2 (10.14 sq mi) |

| • Land | 100% |

| • Water | 0% |

| Coastline | 24.14 km (15.00 mi) |

| Borders | None |

| Highest point | Niulakita 4.6 metres (15 ft) |

| Lowest point | Pacific Ocean 0 metres (0 ft) |

| Exclusive economic zone | 749,790 km2 (289,500 sq mi) |

The Western Pacific nation of Tuvalu, formerly known as the Ellice Islands, is situated 4,000 kilometers (2,500 mi) northeast of Australia and is approximately halfway between Hawaii and Australia. It lies east-northeast of the Santa Cruz Islands (belonging to the Solomons), southeast of Nauru, south of Kiribati, west of Tokelau, northwest of Samoa and Wallis and Futuna and north of Fiji. It is a very small island country of 26.26 km2 (10.14 sq mi). Due to the spread out islands it has the 38th largest Exclusive Economic Zone of 749,790 km2 (289,500 sq mi). In terms of size, it is the second-smallest country in Oceania.[1]

The islands of Tuvalu consists of three reef islands and six atolls, containing approximately 710 km2 (270 sq mi) of reef platforms.[2] The reef islands have a different structure to the atolls, and are described as reef platforms as they are smaller tabular reef platforms that do not have a salt-water lagoon,[3] although they have a completely closed rim of dry land, with the remnants of a lagoon that has no connection to the open sea or that may be drying up.[4] For example, Niutao has two lakes, which are brackish to saline; and are the degraded lagoon as the result of coral debris filling the lagoon.

The soils of Tuvalu's islands are usually shallow, porous, alkaline, coarse-textured, with carbonate mineralogy and high pH values of up to 8.2 to 8.9.[5] The soils are usually deficient in most of the important nutrients needed for plant growth (e.g., nitrogen, potassium and micronutrients such as iron, manganese, copper and zinc), so garden beds need to be enhanced with mulch and fertiliser to increase their fertility.[5] The Tuvalu islands have a total land area of only about 26 km2, less than 10 sq mi (30 km2).

The land is very low-lying, with narrow coral atolls. The highest elevation is 4.6 metres (15 ft) above sea level on Niulakita. Over 4 decades, there had been a net increase in land area of the islets of 73.5 ha (2.9%), although the changes are not uniform, with 74% increasing and 27% decreasing in size. The sea level at the Funafuti tide gauge has risen at 3.9 mm per year, which is approximately twice the global average.[6] The rising sea levels are identified as creating an increased transfer of wave energy across reef surfaces, which shifts sand, resulting in accretion to island shorelines,[7] although this process does not result in additional habitable land.[8] As of March 2018 Enele Sopoaga, the prime minister of Tuvalu, stated that Tuvalu is not expanding and has gained no additional habitable land.[8]

Tuvalu experiences two distinct seasons, a wet season from November to April and a dry season from May to October.[9] Westerly gales and heavy rain are the predominant weather conditions from November to April, the period that is known as Tau-o-lalo, with tropical temperatures moderated by easterly winds from May to October.

Geography

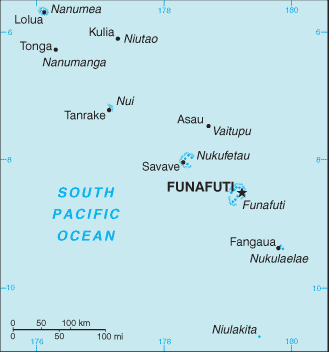

[edit]Location: Oceania, island group of nine islands comprising three reef islands and six true atolls in the South Pacific Ocean.[10] The islands of Tuvalu are spread out between the latitude of 5° to 10° south and longitude of 176° to 180°, west of the International Date Line.[10]

Geographic coordinates: 5°41′S 176°12′E / 5.683°S 176.200°E to 10°45′S 179°51′E / 10.750°S 179.850°E

Map references: Oceania

Area:

total:

26 km2

land:

26 km2

water:

0 km2

Area – comparative: 0.1 times the size of Washington, DC

Land boundaries: 0 km

Coastline: 24.14 kilometres (15.00 mi)

Maritime claims:

contiguous zone:

24.14 nmi (45 km)

exclusive economic zone:

749,790 km2 (289,500 sq mi) and 200 nmi (370 km)

territorial sea:

12 nmi (22 km)

Tuvalu's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) covers an oceanic area of approximately 749,790 km2 (289,500 sq mi).[11]

On 29 August 2012 an Agreement between Tuvalu and Kiribati concerning their Maritime Boundary, was signed by their respective leaders that determined the boundary as being seaward of Nanumea and Niutao in Tuvalu on the one hand and Tabiteuea, Tamana and Arorae in Kiribati on the other hand, along the geodesics connecting the points of latitude and longitude set out in the agreement.[12]

In October 2014 the prime ministers of Fiji and Tuvalu signed the Fiji-Tuvalu Maritime Boundary Treaty, which establishes the extent of the national areas of jurisdiction between Fiji and Tuvalu as recognized in international law under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.[13][14]

Climate: tropical; moderated by easterly trade winds (March to November); westerly gales and heavy rain (November to March).

Terrain: low-lying and narrow coral atolls.

Elevation extremes:

lowest point:

Pacific Ocean 0 m

highest point:

unnamed location, 4.6 metres (15 ft) on Niulakita.

Extreme points:

This is a list of the extreme points of Tuvalu, the points that are farther north, south, east or west than any other location:

- Northernmost point – Lakena islet, Nanumea

- Easternmost point – Niuoko islet, Nukulaelae

- Southernmost point – Niulakita

- Westernmost point – Lakena islet, Nanumea

Natural resources: fish

Land use:

arable land:

0%

permanent crops:

60%

other:

40% (2011)

Irrigated land: NA km2

Trees and shrubs

[edit]Most common trees

[edit]Thaman (2016) described about 362 species or distinct varieties of vascular plants that have been recorded at some time on Tuvalu, of which only about 59 (16%) are possibly indigenous.[15] The most common trees found on all islands are coconut (Cocos nucifera) stands, hibiscus (Hibiscus tiliaceus), papaya (Carica papaya), pandanus (Pandanus tectorius), salt bush (Scaevola taccada), Premna serratifolia, Tournefortia samoensis, zebra wood (Guettarda speciosa), Kanava (Cordia subcordata), (beach cordia) and terminalia (Terminalia samoensis). Indigenous broadleaf species, including Fetau (Calophyllum inophyllum), make up single trees or small stands around the coastal margin.[16] While Coconut palms are common in Tuvalu, they are usually cultivated rather than naturally seeding and growing. Tuvaluan traditional histories are that the first settlers of the islands planted Coconut palms as they were not found on the islands.

The two recorded mangrove species in Tuvalu are the common Togo (Rhizophora stylosa) and the red-flowered mangrove Sagale (Lumnitzera littorea), which is only reported on Nanumaga, Niutao, Nui and Vaitupu. Mangrove ecosystems are protected under Tuvaluan law.[17]

The land cover types found on Funafuti include inland broadleaf forest and woodland, coastal littoral forest and scrub, mangroves and wetlands, and coconut woodland and agroforest.[5]

Native broadleaf forest

[edit]

The native broadleaf forest is limited to 4.1% of the vegetation types on the islands of Tuvalu.[18] The islets of the Funafuti Conservation Area have 40% of the remaining native broadleaf forest on Funafuti atoll. The native broadleaf forest of Funafuti would include the following species, that were described by Charles Hedley in 1896,[19] which include the Tuvaluan name (some of which may follow Samoan plant names):

- Fala or Screw Pine, (Pandanus)

- Puka or pouka, (Hernandia peltata)

- Futu, (Barringtonia asiatica)

- Fetau, (Calophyllum inophyllum)

- Ferra, (Ficus aspem), native fig

- Fau or Fo fafini, or woman's fibre tree (Hibiscus tiliaceus)

- Lakoumonong, (Wedelia strigulosa)

- Lou, (Cardamine sarmentosa)

- Meili, (Polypodium), fern

- Laukatafa, Asplenium nidus, bird's-nest fern

- Milo or miro, (Thespesia populnea)

- Ngashu or Naupaka, (Scaevola taccada)

- Ngia or Ingia, (Pemphis acidula), bush

- Nonou or nonu, (Morinda citrifolia)

- Pukavai, (Pisonia grandis)

- Sageta, (Dioclea violacea), vine

- Talla talla gemoa, (Psilotum triquetrum), fern

- Tausunu or tausoun, (Heliotropium foertherianum)

- Tonga or tongo, (Rhizophora mucronata), found around swamps

- Tulla tulla, (Triumfetta procumbens), whose prostrate stems trailed for several feet over the ground

- Valla valla, (Premna tahitensis)

The blossoms that are valued for their scent and for use in flower necklaces and headdresses include: Fetau, (Calophyllum inophyllum); Jiali, (Gardenia taitensis); Boua (Guettarda speciosa); and Crinum.[19]

Donald Gilbert Kennedy, the resident District Officer in the administration of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony from 1932 to 1938, identified other trees found in the broadleaf forest:[20]

- Pua, (Guettarda speciosa)

- Kanava, (Cordia subcordata)

Charles Hedley (1896) identified the uses of plants and trees from the native broadleaf forest as including:[21]

- Food plants: Coconut; and Ferra, native fig (Ficus aspem).[21]

- Fibre: Coconut; Ferra; Fala, Screw Pine, Pandanus; Fau or Fo fafini, or woman's fibre tree (Hibiscus tiliaceus).[21]

- Timber: Fau or Fo fafini; Pouka, (Hernandia peltata); Ngia or Ingia, (Pemphis acidula); Miro, (Thespesia populnea); and Tonga, (Rhizophora mucronata).[21]

- Dye: Valla valla, (Premna tahitensis); Tonga, (Rhizophora mucronata); and Nonou, (Morinda citrifolia).[21]

- Scent: Fetau, (Calophyllum inophyllum); Jiali, (Gardenia taitensis); and Boua (Guettarda speciosa); Valla valla, (Premna tahitensis); and Crinum.[21]

- Medicinal: Tulla tulla, (Triumfetta procumbens); Nonou, (Morinda citrifolia); Tausoun, (Heliotropium foertherianum); Valla valla, (Premna tahitensis); Talla talla gemoa (Psilotum triquetrum); Lou, (Cardamine sarmentosa); and Lakoumonong, (Wedelia strigulosa).[21]

Thaman (1992) provides a literature review of the ethnobiology of the Pacific Islands.[22]

Climate and natural hazards

[edit]El Niño and La Niña

[edit]Tuvalu experiences the effects of El Niño and La Niña that flow from changes in ocean temperatures in equatorial and central Pacific. El Niño effects increase the chances of tropical storms and cyclones; while La Niña effects increase the chances of drought conditions in Tuvalu. On 3 October 2011, drought conditions resulted in a state of emergency being declared as water reserves ran low.[23][24][25] Typically the islands of Tuvalu receive between 200mm to 400mm of rainfall per month, however a weak La Niña effect causes a drought by cooling the surface of the sea around Tuvalu.

Tropical cyclones

[edit]Severe tropical cyclones are usually rare, but the low level of islands makes them very sensitive to sea-level rise. Tuvalu experienced an average of three cyclones per decade between the 1940s and 1970s, however eight occurred in the 1980s.[26] The impact of individual cyclones is subject to variables including the force of the winds and also whether a cyclone coincides with high tides. A warning system, which uses the Iridium satellite network, was introduced in 2016 in order to allow outlying islands to be better prepare for natural disasters.[27]

George Westbrook recorded a cyclone that struck Funafuti on 23–24 December 1883.[28][29] A cyclone struck Nukulaelae on 17–18 March 1886.[28] Captain Edward Davis of HMS Royalist, who visited the Ellice Group in 1892, recorded in the ship's diary that in February 1891 the Ellice Group was devastated by a severe cyclone.[30] A cyclone caused severe damage to the islands in 1894.[31]

Cyclone Bebe caused severe damage to Funafuti during the 1972–73 South Pacific cyclone season.[32][33] Funafuti's Tepuka Vili Vili islet was devastated by Cyclone Meli in 1979, with all its vegetation and most of its sand swept away during the cyclone.[34] Cyclone Gavin was first identified during 2 March 1997, and was the first of three tropical cyclones to affect Tuvalu during the 1996–97 cyclone season with Cyclones Hina and Keli following later in the season. Cyclone Ofa had a major impact on Tuvalu in late January and early February 1990.[35] On Vaitupu Island around 85 percent of residential homes, trees and food crops were destroyed, while residential homes were also destroyed on the islands of Niutao, Nui and Nukulaelae. The majority of the islands in Tuvalu reported damage to vegetation and crops especially bananas, coconuts and breadfruit, with the extent of damage ranging from 10 to 40 percent. In Funafuti sea waves flattened the Hurricane Bebe bank at the southern end of the airstrip, which caused sea flooding and prompted the evacuation of several families from their homes. In Nui and Niulakita there was a minor loss of the landscape because of sea flooding while there were no lives lost. Soon after the systems had impacted Tuvalu, a Disaster Rehabilitation Sub-Committee was appointed to evaluate the damage caused and make recommendations to the National Disaster Committee and to the Cabinet of Tuvalu, on what should be done to help rehabilitate the affected areas.

In March 2015 Cyclone Pam, the Category 5 cyclone that devastated Vanuatu, caused damage to houses, crops and infrastructure on the outer islands.[36][37][38][39] A state of emergency was subsequently declared on 13 March.[40][41] An estimated 45 percent of the nation's nearly 10,000 people were displaced, according to Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga.[42][43] The three northern islands, Nanumea, Nanumanga and Niutao were badly affected by flooding as the result of storm surges. More than 400 people from the northern island of Nanumanga were moved to emergency accommodation in the school buildings, as well as another 85 families from Nukulaelae in the south of Tuvalu. On Nui the storm surges contaminated the water supplies and damaged septic tanks and grave sites. The central islands of Vaitupu and Nukufetau were also affected by flooding caused by storm surges.[44][45][46] The Situation Report published on 30 March reported that on Nukufetau all the displaced people have returned to their homes.[47]

Nui suffered the most damage of the three central islands (Nui, Nukufetau and Vaitupu);[48] with both Nui and Nukufetau suffering the loss of 90% of the crops.[47] Of the three northern islands (Nanumanga, Niutao, Nanumea), Nanumanga suffered the most damage, with 60–100 houses flooded and damage to the health facility.[47][49] Vasafua islet, part of the Funafuti Conservation Area, was severely damaged by Cyclone Pam. The coconut palms were washed away, leaving the islet as a sand bar.[50][51]

Despite passing over 500 km (310 mi) to the south of the island nation, Cyclone Tino and its associated convergence zone impacted the whole of Tuvalu between January 16 - 19 of 2020.[52][53]

Tsunami

[edit]Nui was struck by a giant wave on 16 February 1882;[54] earthquakes and volcanic eruptions occurring in the basin of the Pacific Ocean and along the Pacific Ring of Fire are a possible cause of a tsunami. There is earthquake activity in the Solomon Islands, where earthquakes occurred in relation to the New Hebrides Trench,[55][56] and movement along the boundary of the Pacific Plate with, respectively, the Indo-Australia, Woodlark, and Solomon Sea plates.[57]

Tuvalu has the third lowest tsunami risk of Pacific Island countries, with a maximum tsunami amplitude of 1.6m for a 2000-year return period (comparatively, the highest is 5.2m for PNG, and the lowest is 1m for Nauru).[58] The assessment of the tsunami risk of Tuvalu was that major source of risk was activity associated with the New Hebrides trench. The orientation of the trench vis-à-vis the islands of Tuvalu results in the conclusion that most of the energy originating from New Hebrides trench is likely to be directed towards the southern islands of Tuvalu, so that the tsunami risk is lower for the northern islands when compared to the southern islands.[58][55][59]

Climate data

[edit]| Climate data for Funafuti (Köppen Af) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.8 (92.8) |

34.4 (93.9) |

34.4 (93.9) |

33.2 (91.8) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.9 (93.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.9 (91.2) |

32.8 (91.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.9 (93.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.7 (87.3) |

30.8 (87.4) |

30.6 (87.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.8 (87.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 28.2 (82.8) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.2 (82.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 25.5 (77.9) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.8 (78.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 22.0 (71.6) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

23.0 (73.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

21.0 (69.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.0 (69.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 413.7 (16.29) |

360.6 (14.20) |

324.3 (12.77) |

255.8 (10.07) |

259.8 (10.23) |

216.6 (8.53) |

253.1 (9.96) |

275.9 (10.86) |

217.5 (8.56) |

266.5 (10.49) |

275.9 (10.86) |

393.9 (15.51) |

3,512.6 (138.29) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 20 | 19 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 16 | 18 | 17 | 19 | 223 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 82 | 81 | 81 | 80 | 81 | 82 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 179.8 | 161.0 | 186.0 | 201.0 | 195.3 | 201.0 | 195.3 | 220.1 | 210.0 | 232.5 | 189.0 | 176.7 | 2,347.7 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 5.8 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 7.5 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 6.4 |

| Source: Deutscher Wetterdienst[60] | |||||||||||||

Environment

[edit]Island, reef and lagoon habitats

[edit]

Tuvalu consists of three reef islands and six true atolls. Its small, scattered group of atolls have poor soil and a total land area of only about 26.26 square kilometres (less than 10 sq. mi.) making it the fourth smallest country in the world. The islets that form the atolls are very low-lying. Nanumaga, Niutao, Niulakita are reef islands and the six true atolls are Funafuti, Nanumea, Nui, Nukufetau, Nukulaelae and Vaitupu. Funafuti is the largest atoll of the nine low reef islands and atolls that form the Tuvalu volcanic island chain. It comprises numerous islets around a central lagoon that is approximately 25.1 kilometres (15.6 miles) (N–S) by 18.4 kilometres (11.4 miles) (W-E), centred on 179°7’E and 8°30’S. On the atolls an annular reef rim surrounds the lagoon, with several natural reef channels.[61] A standard definition of an atoll is "an annular reef enclosing a lagoon in which there are no promontories other than reefs and islets composed of reef detritus".[61] The northern part of the Funafuti lagoon has a deep basin (maximum depth recorded of 54.7 m) basin, and the southern part of the lagoon has very narrow shallow basin.[62]

The eastern shoreline of Fongafale in the Funafuti lagoon (Te Namo) was modified during World War II; several piers were constructed, beach areas filled, and deep water access channels were excavated. These alternations to the reef and shoreline have resulted in changes to wave patterns with less sand accumulating to form the beaches as compared to former times; and the shoreline is now exposed to wave action.[63] Several attempts to stabilize the shoreline have not achieved the desired effect.[64]

The rising population results in increased demand on fish stocks, which are under stress;[65] although the creation of the Funafuti Conservation Area has provided a fishing exclusion area that helps sustain fish populations across the Funafuti lagoon. Population pressure on the resources of Funafuti and in-adequation sanitation systems have resulted in pollution.[66][67] The Waste Operations and Services Act 2009 provides the legal framework for the waste management and pollution control projects funded by the European Union that are directed to organic waste composting in eco-sanitation systems.[68]

Surveys were carried out in May 2010 of the reef habitats of Nanumea, Nukulaelae and Funafuti (including the Funafuti Conservation Area) and a total of 317 fish species were recorded during this Tuvalu Marine Life study. The surveys identified 66 species that had not previously been recorded in Tuvalu, which brings the total number of identified species to 607.[69][70]

The terrestrial invertebrates are land and shore crabs, including Paikea (Discoplax rotunda), Tupa (Cardisoma carnifex), Kamakama (Grapsus albolineatus), a range of hermit crabs, Uga (Coenobita spp) and the coconut crab, Uu (Birgus latro).[17] Also important are a range of land snails, misa (Melampus spp) used to make shell leis (ula) and traditional handicrafts,[71] which includes the decoration of mats, fans and wall hangings.[72]

Environment – climate change issues

[edit]Since there are no streams or rivers and groundwater is not potable, most water needs must be met by catchment systems with storage facilities; beachhead erosion because of the use of sand for building materials; excessive clearance of forest undergrowth for use as fuel; damage to coral reefs from the bleaching of the coral as a consequence of the increase of the ocean temperatures and acidification from increased levels of carbon dioxide; Tuvalu is very concerned about global increases in greenhouse gas emissions and their effect on rising sea levels, which threaten the country's underground water table. Tuvalu has adopted a national plan of action as the observable transformations over the last ten to fifteen years show Tuvaluans that there have been changes to the sea levels.[73]

Because of the low elevation, the islands that make up this nation are threatened by current and future sea level rise.[66] The highest elevation is 4.6 metres (15 ft) above sea level on Niulakita,[74] which gives Tuvalu the second-lowest maximum elevation of any country (after the Maldives). However, the highest elevations are typically in narrow storm dunes on the ocean side of the islands which are prone to over topping in tropical cyclones, such as occurred on Funafuti with Cyclone Bebe.[75]

Tuvalu is mainly composed of coral debris eroded from encircling reefs and pushed up onto the islands by winds and waves.[76] Paul Kench at the University of Auckland in New Zealand and Arthur Webb at the South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission in Fiji released a study in 2010 on the dynamic response of reef islands to sea level rise in the central Pacific. Tuvalu was mentioned in the study, and Webb and Kench found that seven islands in one of its nine atolls have spread by more than 3 per cent on average since the 1950s.[77] One island, Funamanu, gained 0.44 hectares, or nearly 30 per cent of its previous area. In contrast, Tepuka Vili Vili has suffered a net loss in area of 22 percent since 1896. The shape and orientation of the reef has also changed over time.[76]

Further research by Kench et al., published in 2018 identifies rising sea levels as creating an increased transfer of wave energy across the reef surfaces of the atolls of Tuvalu, which shifts sand, resulting in accretion to island shorelines. Over 4 decades, there had been a net increase in land area of the islets of 73.5 ha (2.9%), although the changes are not uniform, with 74% increasing and 27% decreasing in size.[7] However, this process does not result in additional habitable land.[8]

The storm surge resulting from a tropical cyclone can dramatically shift coral debris. In 1972 Funafuti was in the path of Cyclone Bebe. Tropical Cyclone Bebe was a pre-season tropical cyclone that impacted the Gilbert, Ellice Islands, and Fiji island groups.[78] The storm surge created a wall of coral rubble along the ocean side of Fongafale and Funafala that was about 10 miles (16 km) long, and about 10 to 20 feet (3.0 to 6.1 m) thick at the bottom.[79] The cyclone knocked down about 90% of the houses and trees on Funafuti and contaminated sources of drinking water as a result of the system's storm surge and fresh water flooding.

Tuvalu is affected by perigean spring tide events which raise the sea level higher than a normal high tide.[80] The highest peak tide recorded by the Tuvalu Meteorological Service was 3.4 metres (11 ft) on 24 February 2006 and again on 19 February 2015.[81] As a result of historical sea level rise, the king tide events lead to flooding of low-lying areas, which is compounded when sea levels are further raised by La Niña effects or local storms and waves.[82] In the future, sea level rise may threaten to submerge the nation entirely as it is estimated that a sea level rise of 20–40 centimetres (7.9–15.7 inches) in the next 100 years could make Tuvalu uninhabitable.[83][84]

Tuvalu experiences westerly gales and heavy rain from October to March – the period that is known as Tau-o-lalo; with tropical temperatures moderated by easterly winds from April to November. Drinking water is mostly obtained from rainwater collected on roofs and stored in tanks; these systems are often poorly maintained, resulting in lack of water.[85] Aid programs of Australia and the European Union have been directed to improving the storage capacity on Funafuti and in the outer islands.[86]

Borrow Pits Remediation (BPR) project

[edit]When the airfield, which is now Funafuti International Airport, was constructed during World War II. The coral base of the atoll was used as fill to create the runway. The resulting borrow pits impacted the fresh-water aquifer. In the low areas of Funafuti the sea water can be seen bubbling up through the porous coral rock to form pools with each high tide.[87][88][89] Since 1994 a project has been in development to assess the environmental impact of transporting sand from the lagoon to fill all the borrow pits and low-lying areas on Fongafale. In 2013 a feasibility study was carried out and in 2014 the Tuvalu Borrow Pits Remediation (BPR) project was approved, so that all ten borrow pits would be filled, leaving Tafua Pond, which is a natural pond.[90] The New Zealand Government funded the BPR project.[91] The project was carried out in 2015 with 365,000 sqm of sand being dredged from the lagoon to fill the holes and improve living conditions on the island. This project increased the usable land space on Fongafale by eight per cent.[92]

Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project (TCAP)

[edit]The Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project (TCAP) was launched in 2017 for the purpose on enhancing the resilience of the islands of Tuvalu to meet the challenges resulting from higher sea levels.[93] Tuvalu was the first country in the Pacific to access climate finance from Green Climate Fund, with the support of the UNDP.[93] In December 2022, work on the Funafuti reclamation project commenced. The project is to dredge sand from the lagoon to construct a platform on Fongafale, Funafuti that is 780 metres (2,560 ft) meters long and 100 metres (330 ft) meters wide, giving a total area of approximately 7.8 ha. (19.27 acres), which is designed to remain above sea level rise and the reach of storm waves beyond the year 2100.[93] The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) also provided funding for the TCAP. Further projects that are part of TCAP are capital works on the outer islands of Nanumea and Nanumaga aimed at reducing exposure to coastal damage resulting from storms.[93]

Topographic and Bathymetric Survey

[edit]In May 2019, TCAP signed an agreement with Fugro, for it to carry out an airborne LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) survey across the nine islands of Tuvalu.[94] LIDAR is a remote sensing method that uses light in the form of a pulsed laser that will produce high quality mapping of the reef and lagoon bathymetry (sea floor mapping to 50-meter depths) and accurate topography (land elevation data).[94] This aerial survey will provide high quality baseline data to assess the relationship between water levels and wave dynamics and their impact on the islands of Tuvalu.[94] The survey will also provide baseline data for shoreline monitoring, coastal vulnerability assessment and planning.[94]

Controls on plastic waste and recycling of domestic waste

[edit]From 1 August 2019, specific single-use plastic items are subject to a ban on importation into Tuvalu, an importation levy was also imposed on specific items, such as refrigerators and vehicles, to raise money to pay for their recycling or shipment out of the country when they cease to be usable.[95] The new rules are contained in two regulations: the Waste Management (Prohibition on the Importation of Single-Use Plastic) Regulation 2019 and the Waste Management (Levy Deposit) Regulation 2019, which regulations are made under the Waste Operations and Services Act 2009.[95]

Environment – international agreements

[edit]Tuvalu is a party to:

Biodiversity, Climate Change, Climate Change-Kyoto Protocol, Desertification, Law of the Sea, Ozone Layer Protection, Ship Pollution, Whaling

signed, but not ratified: none

Tuvalu signed the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 1992, and ratified it in December 2002.[96][97]

Tuvalu signed the Pacific Islands Cetaceans Memorandum of Understanding on 9 September 2010.

Tuvalu is a party to the Waigani Convention that bans the importation into forum island countries of hazardous and radioactive wastes and to control the transboundary movement and management of hazardous wastes within the south pacific region and is also a party to the Minamata Convention on Mercury, Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer and the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. Tuvalu is in the process of completing its accession to the Basel Convention to protect human health and the environment against the adverse effects that may result from the generation, transboundary movements and management of hazardous and other wastes.[98]

Funafuti atoll

[edit]Structure of Funafuti atoll

[edit]

Funafuti atoll consists of a narrow sweep of land between 20 and 400 metres (66 and 1,312 feet) wide, encircling a large lagoon (Te Namo) of about 18 km (11 miles) long and 14 km (9 miles) wide. The average depth in the Funafuti lagoon is about 20 fathoms (37 metres; 120 feet).[99] With a surface of 275 square kilometres (106.2 sq mi), it is by far the largest lagoon in Tuvalu. The northern part of the lagoon has a deep basin (maximum depth recorded of 54.7 m) basin, and the southern part of the lagoon has very narrow shallow basin.[62] The land area of the 33 islets aggregates to 2.4 square kilometres (0.9 sq mi), less than one percent of the total area of the atoll.

The boreholes on Fongafale islet at the site now called Darwin's Drill,[100] are the result of drilling conducted by the Royal Society of London for the purpose of investigating the formation of coral reefs to determine whether traces of shallow water organisms could be found at depth in the coral of Pacific atolls. This investigation followed the work on The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs conducted by Charles Darwin in the Pacific. Drilling occurred in 1896, 1897 and 1898.[101] Professor Edgeworth David of the University of Sydney was a member of the 1896 "Funafuti Coral Reef Boring Expedition of the Royal Society", under Professor William Sollas and lead the expedition in 1897.[102] However, the geologic history of atolls is more complex than Darwin (1842) and Davis (1928)[103] envisioned.[104][105] The survey of the atoll published in 1970 described its structure as being:

“Funafuti is an almost circular and conical submarine mountain 12,000 feet high, originally volcanic, and of immense geological age, much older than the relatively young and active mountains of the New Hebrides and Solomons. At its base on the ocean bed it is 30 miles wide in one of the directions tested, and 28 miles wide on the other. It rises in a gentle slope which gradually steepens to a point 2,400 feet below water level, after which it rises at an angle of 80 degrees to 840 feet below water level. From this point it rises vertically, like an enormous pillar, till reaches the surface in the form of a reef enclosing a lagoon of irregular size, but of which the extremities give a measurement of 13.5 by 10.0 miles".[99]

Aquifer salinization of Fongafale Islet, Funafuti

[edit]The investigation of groundwater dynamics of Fongafale Islet, Funafuti, show that tidal forcing results in salt water contamination of the surficial aquifer during spring tides.[106] The degree of aquifer salinization depends on the specific topographic characteristics and the hydrologic controls in the sub-surface of the atoll. About half of Fongafale islet is reclaimed swamp that contains porous, highly permeable coral blocks that allow the tidal forcing of salt water.[107] There was extensive swamp reclamation during World War II to create the air field that is now the Funafuti International Airport. As a consequence of the specific topographic characteristics of Fongafale, unlike other atoll islands of a similar size, Fongafale does not have a thick freshwater lens.[107] The narrow fresh water and brackish water sheets in the sub-surface of Fongafale islet results in the taro swamps and the fresh groundwater resources of the islet being highly vulnerable to salinization resulting from the rising sea-level.[107]

In addition to the increased risk of salinized by the sea-level rise, the freshwater lens is at risk from over extraction due to the large population that now occupies Fongafale islet; the increased extraction can be exacerbated by a decrease of the rainfall recharge rate associated with the climate change.[106] Water pollution is also a chronic problem, with domestic wastewater identified as the primary pollution source.[108] Approximately 92% of households on Fongafale islet have access to septic tanks and pit toilets. However, these sanitary facilities are not built as per the design specifications or they are not suitable for the geophysical characteristics, which results in seepage into the fresh water lens and run off into coastal waters.[108]

On Funafuti and on the other islands, rainwater collected off the corrugated iron roofs of buildings is now the primary source of fresh water. On Funafuti a desalination unit that was donated by Japan in 2006 also provides fresh water.[109] In response to the 2011 drought, Japan funded the purchase of a 100 m3/d desalination plant and two portable 10 m3/d plants as part of its Pacific Environment Community (PEC) program.[110][111] Aid programs from the European Union[86][112] and Australia also provided water tanks as part of the longer-term solution for the storage of available fresh water.

Aquifer salinization and the impact on Pulaka production

[edit]Swamp taro (Cyrtosperma merkusii), known in Tuvalu as Pulaka, is grown in large pits of composted soil below the water table,[113] Pulaka has been the main source for carbohydrates,[113] it is similar to taro, but "with bigger leaves and larger, coarser roots".[114]

In recent years the Tuvaluan community have raised concerns over increased salinity of the groundwater in pits that are used to cultivate pulaka.[115] Pits on all islands of Tuvalu (except Niulakita) were surveyed in 2006. Nukulaelae and Niutao each had one pit area in which salinity concentrations thought to be too high for successful swamp taro growth. However, on Fongafale in Funafuti all pits surveyed were either too saline or very marginal for swamp taro production, although a more salt tolerant species of taro (Colocasia esculenta) was being grown in Fongafale.[116]

The extent of the salinization of the aquifer on Fongafale Islet is the result of both man-made changes to the topography that occurred when the air field was built in World War II by reclaiming swamp land and excavating coral rock from other parts of the islet. These topographic changes are exacerbated by the groundwater dynamics of the islet, as tidal forcing pushes salt water into the surficial aquifer during spring tides.[106]

The freshwater lens of each atoll is a fragile system. Tropical cyclones and other storm events also result in wave wash over and extreme high water also occurs during spring tides. These events can result in salt water contamination of the fresh groundwater lens. Periods of low rainfall can also result in contraction of the freshwater lens as the coconut trees and other vegetation draw up the water at a greater than recharge than it can be recharged. The over extraction of ground water to supply human needs has a similar result as drought conditions.[117]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Rodgers, K. A., and Carol Cantrell. The biology and geology of Tuvalu: an annotated bibliography. No. 1. Australian Museum, 1988.

- ^ Morris, C., & Mackay, K. (2008). Status of coral reefs in the Southwest Pacific: Fiji, Nauru, New Caledonia, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu and Vanuatu (Report). Status of coral reefs of the world (Townsville: Australian Institute of Marine Science). pp. 177–188.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Paul S. Kench, Murray R. Ford & Susan D. Owen (9 February 2018). "Patterns of island change and persistence offer alternate adaptation pathways for atoll nations (Supplementary Note 1)". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 605. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..605K. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02954-1. PMC 5807422. PMID 29426825.

- ^ Hedley, Charles (1896). "General account of the Atoll of Funafuti" (PDF). Australian Museum Memoir. 3 (2): 1–72. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1967.3.1896.487. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ a b c "Tuvalu Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity". Government of Tuvalu. 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ Paul S. Kench, Murray R. Ford & Susan D. Owen (9 February 2018). "Patterns of island change and persistence offer alternate adaptation pathways for atoll nations (Supplementary Note 2)". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 605. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..605K. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02954-1. PMC 5807422. PMID 29426825.

- ^ a b Paul S. Kench, Murray R. Ford & Susan D. Owen (9 February 2018). "Patterns of island change and persistence offer alternate adaptation pathways for atoll nations". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 605. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..605K. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-02954-1. PMC 5807422. PMID 29426825.

- ^ a b c "TUVALU PM REFUTES AUT RESEARCH". 19 March 2018. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ "Current and Future Climate of Tuvalu" (PDF). Tuvalu Meteorological Service, Australian Bureau of Meteorology & Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Maps of Tuvalu". Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ A J Tilling; Ms E Fihaki (17 November 2009). Tuvalu National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (PDF). Fourth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity. p. 7.

- ^ "Agreement between Tuvalu and Kiribati concerning their Maritime Boundary" (PDF). U.N. 29 August 2012.

- ^ "Fiji Tuvalu Maritime Boundary Treaty". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Fiji. 17 October 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "Fiji and Tuvalu sign maritime boundary agreement". Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) Geoscience Division. 24 October 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ Thaman, Randolph (October 2016). "The Flora of Tuvalu: Lakau Mo Mouku o Tuvalu". Atoll Research Bulletin (611): xii-129. doi:10.5479/si.0077-5630.611. S2CID 89181901.

- ^ FCG ANZDEC Ltd (7 October 2020). Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project: Environmental and Social Impact Assessment - Funafuti (Report). The Pacific Community. p. 53. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ a b FCG ANZDEC Ltd (7 August 2020). Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project: Environmental and Social Impact Assessment - Nanumaga and Nanumea (Report). The Pacific Community. p. 66. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ Randy Thaman, Feagaiga Penivao, Faoliu Teakau, Semese Alefaio, Lamese Saamu, Moe Saitala, Mataio Tekinene and Mile Fonua (2017). "Report on the 2016 Funafuti Community-Based Ridge-To-Reef (R2R)" (PDF). Rapid Biodiversity Assessment of the Conservation Status of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (BES) In Tuvalu. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hedley, Charles (1896). General account of the Atoll of Funafuti (PDF). Australian Museum Memoir 3(2): 1–72. pp. 30–40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ Kennedy, Donald (1931). The Ellice Islands Canoe Journal of the Polynesian Society Memoir no. 9. Journal of the Polynesian Society. pp. 71–100. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hedley, Charles (1896). General account of the Atoll of Funafuti (PDF). Australian Museum Memoir 3(2): 1–72. pp. 40–41. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ Thaman, R.R. (May 1992). "Batiri Kei Baravi: The Ethnobotany of Pacific Island Coastal Plants" (PDF). Atoll Research Bulletin. 361 (361). National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution: 1–62. doi:10.5479/si.00775630.361.1. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Tuvalu's crippling drought offers important lessons to the Pacific". Secretariat of the Pacific Community. 6 October 2011. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Benns, Matthew (3 October 2011). "Tuvalu 'to run out of water by Tuesday'". The Telegraph. London.

- ^ Macrae, Alistair (11 October 2011). "Tuvalu in a fight for its life". The Drum – Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ Connell, John (2015). "Vulnerable Islands: Climate Change, Techonic Change, and Changing Livelihoods in the Western Pacific" (PDF). The Contemporary Pacific. 27 (1): 1–36. doi:10.1353/cp.2015.0014.

- ^ "Tuvalu to introduce new early warning system". Radio New Zealand. 10 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b McLean, R.F. and Munro, D. (1991). "Late 19th century Tropical Storms and Hurricanes in Tuvalu" (PDF). South Pacific Journal of Natural History. 11: 213–219. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Resture, Jane. Hurricane 1883. Tuvalu and the Hurricanes: 'Gods Who Die' by Julian Dana as told by George Westbrook.

- ^ Resture, Jane (17 May 2004). "Tuvalu and the hurricanes". Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ Taafaki, Pasoni (1983). "Chapter 2 – The Old Order". In Laracy, Hugh (ed.). Tuvalu: A History. Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific and Government of Tuvalu. p. 27.

- ^ Resture, Jane (14 October 2022). "Hurricane Bebe Left 19 People Dead And Thousands Misplaced In Fiji and Tuvalu". Janeresture.com. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ "Life bounce back in the Ellice". 44(5) Pacific Islands Monthly. 1 May 1966. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ "Kogatapu Funafuti Conservation Area". Tuvaluislands.com. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ Koop, Neville L; Fiji Meteorological Service (Winter 1991). DeAngellis, Richard M (ed.). Samoa Depression (Mariners Weather Log). Vol. 35. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Oceanographic Data Service. p. 53. ISSN 0025-3367. OCLC 648466886.

- ^ "Wild weather in Tuvalu". Tuvalu Solar Project Team Blog. 11 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ "Flooding in Vanuatu, Kiribati and Tuvalu as Cyclone Pam strengthens". SBS Australia. 13 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ "State of emergency in Tuvalu". Radio New Zealand International. 14 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ "45 percent of Tuvalu population displaced – PM". Radio New Zealand International. 15 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ "Press Release issued by the Office of the Prime Minister" (PDF). Fenui News. 13 March 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ "State of emergency in Tuvalu". Radio New Zealand International. 14 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ "45 percent of Tuvalu population displaced – PM". Radio New Zealand International. 15 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ "International assistance due today in Tuvalu". Radio New Zealand International. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Tuvalu: Tropical Cyclone Pam (PDF). International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (Report). ReliefWeb. 16 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ "One Tuvalu island evacuated after flooding from Pam". Radio New Zealand International. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "Tuvalu: Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report No. 1 (as of 22 March 2015)". Relief Web. 22 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ a b c "Tuvalu: Tropical Cyclone Pam Situation Report No. 2 (as of 30 March 2015)". Relief Web. 30 March 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ "Forgotten paradise under water". United Nations Development Programme. 1 May 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ "Tuvalu situation update: Securing health from disastrous impacts of cyclone Pam in Tuvalu". Relief Web/World health Organisation – Western Pacific Region. 3 April 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- ^ Wilson, David (4 July 2015). "Vasafua Islet vanishes". Tuvalu-odyssey.net. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ Endou, Shuuichi (28 March 2015). "バサフア島、消失・・・(Vasafua Islet vanishes)". Tuvalu Overview (Japanese). Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ Special Weather Bulletin Number 1 for Tuvalu January 16, 2020 10z (Report). Fiji Meteorological Service. 16 January 2020.

- ^ ""It swept right over": Tuvalu inundated by waves whipped up by Cyclone Tino". Radio New Zealand. 20 January 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ Pape, Sotaga (1983). "10". In Laracy, Hugh (ed.). Tuvalu: A History (Chapter 10) Nui. Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific and Government of Tuvalu. p. 76.

- ^ a b FCG ANZDEC Ltd (7 October 2020). Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project: Environmental and Social Impact Assessment - Funafuti (Report). The Pacific Community. p. 50. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ FCG ANZDEC Ltd (7 August 2020). Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project: Environmental and Social Impact Assessment - Nanumaga and Nanumea (Report). The Pacific Community. p. 61. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "Magnitude 8.1 – SOLOMON ISLANDS – Summary". USGS Earthquake Hazards Program. Archived from the original on 6 April 2007. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- ^ a b Thomas, C.; Burbidge, D (2009). A Probabilistic Tsunami Hazard. Assessment of the Southwest Pacific Nations. Geoscience Australia Professional Opinion No.2009/02. Rereleased 2011/11 (PDF) (Report). Geoscience Australia (GA). Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ FCG ANZDEC Ltd (7 August 2020). Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project: Environmental and Social Impact Assessment - Nanumaga and Nanumea (Report). The Pacific Community. p. 61. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Funafuti / Tuvalu (Ellice-Inseln)" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ^ a b McNeil, F. S. (1954). "Organic reefs and banks and associated detrital sediments". Am. J. Sci. 252 (7): 385–401. Bibcode:1954AmJS..252..385M. doi:10.2475/ajs.252.7.385.

- ^ a b "EU-SOPAC Project Report 50: TUVALU TECHNICAL REPORT High-Resolution Bathymetric Survey Fieldwork undertaken from 19 September to 24 October 2004" (PDF). Pacific Islands Applied Geoscience Commission c/o SOPAC Secretariat. October 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "Fogafale: Then and Now (1941 & 2003)". tuvaluislands.com. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Carter, Ralf (4 July 1986). "Wind and Sea Analysis – Funafuti Lagoon, Tuvalu". South Pacific Regional Environmental Programme and UNDP Project RAS/81/102 (Technical. Report No. 58 of PE/TU.3). Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ Lusama, Tafue (29 November 2011). "Tuvalu plight must be heard by UNFCC". The Drum – Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b Krales, Amelia Holowaty (18 October 2011). "As Danger Laps at Its Shores, Tuvalu Pleads for Action". The New York Times – Green: A Blog about Energy and the Environment. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Baarsch, Florent (4 March 2011). "Warming oceans and human waste hit Tuvalu's sustainable way of life". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ "Tuvalu / Water, Waste and Sanitation Project (TWWSP): CRIS FED/2009/021-195, ANNEX" (PDF). European Union. 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Sandrine Job; Daniela Ceccarelli (December 2011). "Tuvalu Marine Life Synthesis Report" (PDF). Alofa Tuvalu project with the Tuvalu Fisheries Department. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ Sandrine Job; Daniela Ceccarelli (December 2012). "Tuvalu Marine Life Scientific Report" (PDF). Alofa Tuvalu project with the Tuvalu Fisheries Department. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ Randy Thaman, Feagaiga Penivao, Faoliu Teakau, Semese Alefaio, Lamese Saamu, Moe Saitala, Mataio Tekinene and Mile Fonua (2017). "Report on the 2016 Funafuti Community-Based Ridge-To-Reef (R2R)" (PDF). Rapid Biodiversity Assessment of the Conservation Status of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (BES) in Tuvalu. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tiraa-Passfield, Anna (September 1996). "The uses of shells in traditional Tuvaluan handicrafts" (PDF). SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin #7. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ "Tuvalu's National Adaptation Programme of Action" (PDF). Department of Environment of Tuvalu. May 2007. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ^ Lewis, James (December 1989). "Sea level rise: Some implications for Tuvalu". The Environmentalist. 9 (4): 269–275. doi:10.1007/BF02241827. S2CID 84796023.

- ^ Tropical Cyclones in the Northern Australian Regions 1971–1972. Bureau of Meteorology, Australian Government Publishing Service. 1975.

- ^ a b Warne, Kennedy (13 February 2015). "Will Pacific Island Nations Disappear as Seas Rise? Maybe Not – Reef islands can grow and change shape as sediments shift, studies show". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ Plumer, Bradford (7 June 2010). "Pacific Islands Defying Sea-Level Rise—For Now". New Republic. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ^ Bureau of Meteorology (1975) Tropical Cyclones in the Northern Australian Regions 1971–1972 Australian Government Publishing Service

- ^ Resture, Jane (5 October 2009). "Hurricane Bebe 1972". Tuvalu and the Hurricanes: 'The Hurricane in Funafuti, Tuvalu' by Pasefika Falani (Pacific Frank). Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Shukman, David (22 January 2008). "Tuvalu struggles to hold back tide". BBC News. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ "Tuvalu surveys road damage after king tides". Radio New Zealand. 24 February 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Eliuta, Niuone (15 February 2024). "Science says Tuvalu will drown within decades; the reality is worse". PolicyDevBlog. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ Patel SS (2006). "A sinking feeling" (PDF). Nature. 440 (7085): 734–736. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..734P. doi:10.1038/440734a. PMID 16598226. S2CID 1174790.

- ^ Hunter, J. A. 2002. Note on Relative Sea Level Change at Funafuti, Tuvalu Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 13 May 2006.

- ^ Kingston, P.A. (2004). "Surveillance of Drinking Water Quality in the Pacific Islands: Situation Analysis and Needs Assessment". Situation Analysis and Needs Assessment, Country Reports, WHO. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Tuvalu – 10th European Development Fund". Delegation of the European Union. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ Laafai, Monise (October 2005). "Funafuti King Tides". Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ Mason, Moya K. "Tuvalu: Flooding, Global Warming, and Media Coverage". Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- ^ Holowaty Krales, Amelia (20 February 2011). "Chasing the Tides, parts I & II". Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ Silafaga Lalua Melton (28 October 2014). "73 years of waiting finally pays off for Funafuti". Fenui News. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ "Tuvalu to Benefit from International Dredging Aid". Dredging News. 1 April 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ "Coast contractor completes aid project in remote Tuvalu". SunshineCoastDaily. 27 November 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d Bouadze, Levan (6 December 2022). "Groundbreaking ceremony in Funafuti for Tuvalu's coastal adaptation". UNDP Pacific Office in Fiji. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Advanced Topographic and Bathymetric Survey to Support Tuvalu's Adaptation Efforts". UNDP. 2 May 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ a b Buchanan, Kelly (19 August 2019). "Tuvalu: Ban on Single-Use Plastics Commences". Library of Congress. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ "Tuvalu Sixth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity" (PDF). Government of Tuvalu. 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ Compiled by Randy Thaman with assistance from Faoliu Teakau, Moe Saitala, Epu Falega, Feagaiga Penivao, Mataio Tekenene and Semese Alefaio (2016). "Tuvalu National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan: Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Trade, Tourism, Environment and Labour Government of Tuvalu. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Assessment of Legislative Frameworks Governing Waste Management in Tuvalu" (PDF). Prepared by the Melbourne Law School at the University of Melbourne, Australia, with technical assistance from Monash University, on behalf of the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP). November 2020. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ a b Coates, A. (1970). Western Pacific Islands. H.M.S.O. p. 349.

- ^ Lal, Andrick. South Pacific Sea Level & Climate Monitoring Project – Funafuti atoll (PDF). SPC Applied Geoscience and Technology Division (SOPAC Division of SPC). pp. 35 & 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2014.

- ^ "TO THE EDITOR OF THE HERALD". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 11 September 1934. p. 6. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ David, Mrs Edgeworth, Funafuti or Three Months on a Coral Atoll: an unscientific account of a scientific expedition, London: John Murray, 1899

- ^ Davis, W.M. (1928). "The coral reef problem". American Geographical Society Special Publication. 9: 1–596.

- ^ Stoddart, D. R. (1994). "Theory and Reality: The Success and Failure of the Deductive Method in Coral Reef Studies–Darwin to Davis". Earth Sciences History. 13 (1): 21–34. doi:10.17704/eshi.13.1.wp354u3281532021.

- ^ Dickinson, William R. (2009). "Pacific Atoll Living: How Long Already and Until When?" (PDF). GSA Today. 19 (3): 4–10. doi:10.1130/GSATG35A.1.

- ^ a b c Nakada S.; Yamano H.; Umezawa Y.; Fujita M.; Watanabe M.; Taniguchi M. (2010). "Evaluation of Aquifer Salinization in the Atoll Islands by Using Electrical Resistivity". Journal of the Remote Sensing Society of Japan. 30: 317–330. doi:10.11440/rssj.30.317.

- ^ a b c Nakada S, Umezawa Y, Taniguchi M, Yamano H (July–August 2012). "Groundwater dynamics of Fongafale Islet, Funafuti Atoll, Tuvalu". Groundwater. 50 (4): 639–44. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6584.2011.00874.x. PMID 22035506. S2CID 32336745.

- ^ a b Fujita M., Suzuki J., Sato D., Kuwahara Y., Yokoki H., Kayanne, Y. (2013). "Anthropogenic impacts on water quality of the lagoonal coast of Fongafale Islet, Funafuti Atoll, Tuvalu" (PDF). Sustainability Science. 8 (3): 381–390. doi:10.1007/s11625-013-0204-x. S2CID 127909606.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Japan Provides Desalination Plant to relieve Tuvalu's water problems". Embassy of Japan in the Republic of the Fiji Islands. 2 June 2006. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ "Japan-New Zealand Aid Cooperation in response to severe water shortage in Tuvalu". Department of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 4 November 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ "Japanese fund three desalination plants for Tuvalu". The International Desalination & Water Reuse Quarterly industry website. 17 October 2011. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ^ "Tuvalu / Water, Waste and Sanitation Project (TWWSP): CRIS FED/2009/021-195, ANNEX" (PDF). European Union. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ a b Koch, Gerd (1983). The material culture of Tuvalu. Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific. p. 46. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ "Leaflet No. 1 – Revised 1992 – Taro". Food and Agriculture Organization. 1992. Archived from the original on 28 August 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ "Tuvalu could lose root crop". Radio New Zealand. 17 September 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- ^ Webb, Dr Arthur (March 2007). "Tuvalu Technical Report: Assessment of Salinity of Groundwater in Swamp Taro (Cyrtosperma Chamissonis) "Pulaka" Pits in Tuvalu". Pacific Islands Applied Geoscience Commission, EU EDF8-SOPAC Project Report 75: Reducing Vulnerability of Pacific ACP States. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ Nakada S, Umezawa Y, Taniguchi M, Yamano H (2012). "Groundwater dynamics of Fongafale Islet, Funafuti Atoll, Tuvalu". Groundwater. 50 (4): 639–44. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6584.2011.00874.x. PMID 22035506. S2CID 32336745.

Further reading

[edit]- (in English) Kench, Thompson, Ford, Ogawa and McLean (2015). "GSA DATA REPOSITORY 2015184 (Changes in planform characteristics of 29 islands located on Funafuti's atoll rim)" (PDF). The Geological Society of America. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Compiled by Randy Thaman with assistance from Faoliu Teakau, Moe Saitala, Epu Falega, Feagaiga Penivao, Mataio Tekenene and Semese Alefaio (2016). "Tuvalu National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan: Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Trade, Tourism, Environment and Labour Government of Tuvalu. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Thaman, Randolph (October 2016). "The Flora of Tuvalu: Lakau Mo Mouku o Tuvalu". Atoll Research Bulletin (611): xii-129. doi:10.5479/si.0077-5630.611. S2CID 89181901.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.