James and the Giant Peach (film)

| James and the Giant Peach | |

|---|---|

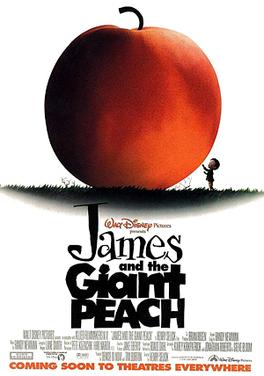

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Henry Selick |

| Screenplay by | Karey Kirkpatrick Jonathan Roberts Steve Bloom |

| Based on | James and the Giant Peach by Roald Dahl |

| Produced by | Denise Di Novi Tim Burton |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Pete Kozachik Hiro Narita |

| Edited by | Stan Webb |

| Music by | Randy Newman |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution (Worldwide) Guild Film Distribution[1] (United Kingdom) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 79 minutes |

| Countries | United Kingdom United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $38 million |

| Box office | $37.7 million[2] |

James and the Giant Peach is a 1996 musical fantasy film directed by Henry Selick, based on the 1961 novel of the same name by Roald Dahl.[3] It was produced by Tim Burton and Denise Di Novi, and starred Paul Terry as James. The film is a combination of live action and stop-motion animation. Joanna Lumley and Miriam Margolyes played James's self-absorbed Aunts Spiker and Sponge, respectively (in the live-action segments), with Simon Callow, Richard Dreyfuss, Jane Leeves, Susan Sarandon and David Thewlis, as well as Margolyes, voicing his insect friends in the animation sequences.

Released on April 12, 1996 in the United States, the film received generally positive reviews from critics, who praised its story and visual aspects.[4] However, the film was a box office failure, grossing $300,000 less than its budget.

Plot

In the summer of 1948, English boy James Henry Trotter is a young orphan living with his sadistic and domineering aunts Spiker and Sponge after his parents were "eaten alive" by a rhinoceros.

One day, after rescuing a spider from his hysterical aunts, James obtains magic "crocodile tongues" from a mysterious old man, which have the power to grow anything they come into contact with to colossal size. James, running home, trips and spills the bag onto the ground; the neon, wormlike "tongues" leap away and into the ground underneath an old peach tree, thus growing a massive fruit that Spiker and Sponge exploit as a tourist attraction.

At night, James eats through the peach to find a pit with several human-sized anthropomorphic invertebrates: Mr. Grasshopper, Mr. Centipede, Ms. Spider (the spider he saved prior), Mr. Earthworm, Mrs. Ladybug, and Mrs. Glowworm. As they hear Spiker and Sponge searching for James, Centipede cuts the stem connecting the peach to the tree and the peach rolls away to the Atlantic Ocean.

The invertebrates fly the peach to New York City with a flock of seagulls (each tied with a string to the peach stem), as James has dreamed of visiting the Empire State Building like his parents wanted to. Obstacles include a giant mechanical shark and undead skeletal pirates in the Arctic Ocean.

When the group arrives, they are suddenly attacked by the tempestuous form of the rhinoceros that killed James' parents. James, though scared, gets everyone to safety and confronts the rhino before it strikes the peach with lightning.

James and the peach fall to the city below, landing on the Empire State Building. After he is rescued by the biggest crane in New York, Spiker and Sponge arrive and attempt to claim James and the peach. James tells the crowd of his amazing adventure and exposes his aunts' abuses. Enraged at James, Spiker and Sponge attempt to attack him with stolen fire axes, but the insects arrive to save him. Ms. Spider subdues the two aunts by wrapping them up in her silk as a beat cop has the crane remove the aunts. James introduces his friends to the crowd of onlookers, and allows the children to eat the peach.

The peach pit is made into a cottage in Central Park, where James lives happily with the bugs. The newspaper articles reveal the bugs' fame in the city: Mr. Centipede runs for New York mayor and is now James' father; Miss Spider opens a club and is his mother; Mr. Earthworm becomes a mascot for a skin-care company (and either James' uncle or cousin); Mrs. Ladybug becomes an obstetrician and James' aunt; Mr. Grasshopper becomes a concert violinist (and James' grandfather); and Mrs. Glowworm becomes the light in the torch of the Statue of Liberty (and his grandmother). James celebrates his ninth birthday with his new family and friends.

Cast

- Paul Terry as James Henry Trotter, an orphan. Terry also voiced his animated form.

- Miriam Margolyes as Aunt Sponge, the aunt of James who mistreats him ever since taking him in

- Joanna Lumley as Aunt Spiker, the aunt of James who lives with Sponge and mistreats him ever since taking him in

- Pete Postlethwaite as the Magic Man, a man who gives James worm-like tongues and also serves as the film's narrator

- Steven Culp as James' Father who was "eaten alive" by a rhinoceros

- Susan Turner-Cray as James' Mother who was "eaten alive" by a rhinoceros

- Mike Starr as a beat cop in New York City who was among the first to see the peach on the Empire State Building

- Cirocco Dunlap as a girl with a telescope who informs the beat cop about a boy being on top of the peach that landed on the Empire State Building

- Jeff Mosely as a hard hat man who rides on the top of the biggest crane in New York City when removing the peach from the Empire State Building

- Mario Yedidia as a street kid

Voices

- Simon Callow as Mr. Grasshopper

- Richard Dreyfuss as Mr. Centipede

- Jeff Bennett as Mr. Centipede (singing voice, uncredited)

- Jane Leeves as Mrs. Ladybug

- Susan Sarandon as Miss Spider

- David Thewlis as Mr. Earthworm

- Miriam Margolyes as Mrs. Glowworm

- Sally Stevens as Mrs. Glowworm (singing voice, uncredited)

Production

At Walt Disney Animation Studios in the early 1980s, Joe Ranft tried to convince the staff to produce a film based on Roald Dahl's James and the Giant Peach (1961), a book that enamored him with its "liberating" material ever since he first read it in third grade.[5] However, Disney refused for reasons of a potentially expensive and difficult animation process and the source material's weird subject matter.[5] Ranft also tried to pitch the film to Disney through Pixar although the studio settled on a different pitch instead which became Toy Story.[6] Among the animators exposed to the book by Ranft was Henry Selick; while he enjoyed the book and thought about adapting it to screen for several years, he understood the obstacles doing so, such as the source material's dreamy nature, episodic structure, and the reputation of other Dahl books being so agitational some parts of the world banned them.[5]

Felicity Dahl, Roald's widow and executor of his estate, began offering film rights to the book in the summer in 1992; among those interested included Steven Spielberg and Danny DeVito.[7][8]

Walt Disney Pictures acquired the film rights to the book from the Dahl estate in 1992.[9] Brian Rosen was hired as producer by Disney for his experience in animated projects like FernGully: The Last Rainforest (1992) and live-action films such as Mushrooms (1995).[10]

Dennis Potter was hired to write a draft. Rosen described it as "slightly black and bizarre", a tone Disney did not approve of, particularly with the sharks being Nazis. Once Potter died, Karey Kirkpatrick and Bruce Joel Rubin came in to write separate drafts, of which Kirkpatrick's was chosen.[10] Unlike the novel, James's aunts are not killed by the rolling peach (though his parents' deaths occur as in the novel) but follow him to New York.[11] The character Silkworm was removed to not overload on the amount of characters to animate; in the book, her purpose was limited to what Miss Spider did in the film, which was to attach the peach to several seagulls during the shark chase.[12]

To write four songs for the movie, Selick approached Elvis Costello, who showed an interest in doing the film. Unfortunately, Disney's music division showed no interest in Costello. "Their alarms just went off, and they said, 'No, that's too weird,'" said Selick. Disney suggested Randy Newman as an alternative. "I didn't want to use Randy," said Selick, "only because John Lasseter was already using him for Toy Story." Andy Partridge, the lead singer of the rock group XTC, originally wrote four songs for the film, "All I Dream Of Is A Friend", "Don't Let Us Bug Ya", "Stinking Rich Song" and "Everything Will Be All Right", "one of which was very beautiful," said Selick, but was replaced by Newman due to creative differences between Selick and Disney regarding the choice of soundtrack composer and the fact that Disney wanted to own the copyright to the songs for perpetuity.[13][14]

Before the start of production, Disney and Selick debated on whether the film should be live-action or stop-motion-animated, the company skeptical of the stop-motion solution.[10] Selick had originally planned James to be a live actor through the entire film, then later considered doing the whole film in stop-motion; but ultimately settled on entirely live-action and entirely stop-motion sequences, to keep lower costs.[15] The film begins with 20 minutes of live-action,[11] but becomes stop-motion animation after James enters the peach, and then live-action again when James arrives in New York City (although the arthropod characters remained in stop-motion).[15] Like The Wizard of Oz (1939), the color palette changes when James enters the Peach to indicate he has entered a magical setting, from greys and greens to vibrant colors.[10]

Filming began on November 15, 1994, with the live-action scenes wrapping on December 27 of that year, and the stop-motion scenes continuing until January 19, 1996.[16]

Songs

All tracks are written by Randy Newman

| No. | Title | Performer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "My Name Is James" | Paul Terry | |

| 2. | "That's the Life" | Jeff Bennett, Susan Sarandon, Jane Leeves, Miriam Margolyes, Simon Callow & David Thewlis (Paul Terry; reprise) | |

| 3. | "Eating the Peach" | Jeff Bennett, Susan Sarandon, Jane Leeves, Miriam Margolyes, Simon Callow, David Thewlis & Paul Terry | |

| 4. | "Family" | Jeff Bennett, Susan Sarandon, Jane Leeves, Miriam Margolyes, Simon Callow, David Thewlis & Paul Terry | |

| 5. | "Good News" | Randy Newman |

Release

The film was theatrically released on April 12, 1996.

Disney released the film worldwide except for a few countries in Europe including the United Kingdom, where Pathé (the owner of co-producer Allied Filmmakers) handled distribution and sold the rights to independent companies. The only countries where Disney does not have control over the movie are the United Kingdom and Germany, where the film was released by Guild Film Distribution and Tobis Film respectively.

Box office

The film opened at the number 2 spot at the box office, missing out on the top spot to Primal Fear.[17][18] The film took in $7,539,098 that weekend,[19] and stayed in the top 10 for the next 5 weeks before dropping to 11th place.[20] The film went on to gross $28,946,127 in the United States and Canada and $37.7 million worldwide,[21][22][2] which against a budget of $38 million, made the film commercially a box office bomb.[23]

Home media

The film was released on VHS on October 15, 1996. A digitally restored Blu-ray/DVD combo pack was released by Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment on August 3, 2010, in the United States.[24]

Reception

The film received positive reviews during its initial release.

Though Roald Dahl refused numerous offers to have a film version of James and the Giant Peach produced during his lifetime, his widow, Liccy, approved an offer to produce a live-action version. She thought Roald "would have been delighted with what they did with James. It is a wonderful film."[25]

Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 91% based on reviews from 74 critics, with an average score of 7.2/10. The website's critical consensus states: "The arresting and dynamic visuals, offbeat details and light-as-air storytelling make James and the Giant Peach solid family entertainment."[4] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, lists the film with a weighted average score of 78 out of 100 based on 36 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[26] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A-" on an A+ to F scale.[27]

Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly gave the film a positive review, praising the animated part, but calling the live-action segments "crude".[28] Writing in The New York Times, Janet Maslin called the film "a technological marvel, arch and innovative with a daringly offbeat visual conception" and "a strenuously artful film with a macabre edge."[29]

Awards and nominations

The film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Music, Original Musical or Comedy Score, by Randy Newman. It won Best Animated Feature Film at the Annecy International Animated Film Festival.

| Year | Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | Annie Awards | Best Animated Feature | Nominated | |

| Best Individual Achievement: Directing | Henry Selick | Nominated | ||

| Best Individual Achievement: Music | Randy Newman | Nominated | ||

| Best Individual Achievement: Producing | Tim Burton Denise Di Novi |

Nominated | ||

| Best Individual Achievement: Storyboarding | Joe Ranft | Nominated | ||

| Best Individual Achievement: Voice Acting | Richard Dreyfuss | Nominated | ||

| Best Individual Achievement: Writing | Karey Kirkpatrick Jonathan Roberts Steve Bloom |

Nominated | ||

| Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Animated Film | Won | ||

| 1997 | Academy Awards | Best Music, Original Musical or Comedy Score | Randy Newman | Nominated |

| Annecy International Animated Film Festival | Best Animated Feature Film | Henry Selick | Won [30] | |

| Chicago Film Critics Association | Best Original Score | Randy Newman | Nominated | |

| Dallas–Fort Worth Film Critics Association | Best Animated Film | Won | ||

| Satellite Awards | Best Motion Picture, Animated or Mixed Media | Tim Burton Denise Di Novi |

Nominated | |

| Saturn Awards | Best Fantasy Film | Nominated | ||

| Young Artist Awards | Best Family Feature – Animation or Special Effects | Won | ||

| Best Performance in a Voiceover – Young Artist | Paul Terry | Nominated |

Potential remake

In August 2016, Sam Mendes was revealed to be in negotiations with Disney to direct another live action adaptation of the novel,[31] with Nick Hornby in talks for the script.[32] In May 2017, however, Mendes was no longer attached to the project due to his entering talks with Disney about directing a live-action film adaptation of Pinocchio, which he would also drop out on with Robert Zemeckis taking his place.[33]

References

Citations

- ^ "James And The Giant Peach". BBFC. 1996-04-15. Archived from the original on 2022-02-11. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- ^ a b "Top 100 worldwide b.o. champs". Variety. January 20, 1997. p. 14.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. pp. 185–186. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ a b "James and the Giant Peach". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c French 1996b, p. 25.

- ^ Squires, Bethy (August 9, 2024). "Toy Story's Creators on Pixar's Scrappy, DIY Roots". Vulture. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ Thompson, Anne (April 26, 1996). "Behind the scenes of 'James and the Giant Peach'". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ French 1996b, p. 27.

- ^ Setoodah, Ramin (July 29, 2016). "From 'The BFG' to 'Matilda': How 5 Roald Dahl Books Landed on the Big Screen". Variety. Archived from the original on July 3, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- ^ a b c d French 1996a, p. 7.

- ^ a b Nichols, Peter M. (2003). The New York Times Essential Library: Children's Movies. New York: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 134–136. ISBN 0-8050-7198-9.

- ^ French 1996a, p. 61.

- ^ XTC (2019-04-22). "WIKI COR-Re JAMES +GIANT PEACH. "... but was replaced by Randy Newman when he could not get Disney to offer him "an acceptable deal". More than Disney wanted Newman, filmmaker Sellick wanted me. I feel Disney made things difficult for me so that they would get their choice". @xtcfans. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ^ "Cinefantastique Magazine". Archive. 1970. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- ^ a b Evans, Noah Wolfgram. "Layers: A Look at Henry Selick". Archived from the original on January 29, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ^ "James and the Giant Peach (1996)". IMDbPro. Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office : 'Primal Fear' Keeps Grip on Top Spot". Los Angeles Times. 16 April 1996. Archived from the original on 2023-05-06. Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- ^ "Primal Fear". Archived from the original on 2018-02-03. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- ^ "James and the Giant Peach". Archived from the original on 2020-12-20. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- ^ "James and the Giant Peach". Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- ^ "James and the Giant Peach". Archived from the original on 2022-11-07. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- ^ "James and the Giant Peach (1996) – Financial Information". Archived from the original on 2018-03-03. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- ^ "James and the Giant Peach". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ Foster, Dave (May 19, 2010). "James and the Giant Peach (US BD) in August". The Digital Fix. Archived from the original on May 20, 2010. Retrieved June 27, 2010.

- ^ Roberts, Chloe; Darren Horne. "Roald Dahl: From Page to Screen". close-upfilm.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved December 9, 2008.

- ^ "James and the Giant Peach Reviews". Metacritic. Red Ventures. Archived from the original on October 23, 2022. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- ^ "Home". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on 2018-01-02. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (April 19, 1996). "James and the Giant Peach (1996) review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 23, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ^ Maslin review

- ^ "Annecy". Archived from the original on 2019-01-26. Retrieved 2019-01-25.

- ^ "Sam Mendes in Talks to Direct Disney's Live-Action 'James and the Giant Peach'". Variety. 25 August 2016. Archived from the original on 30 August 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ "Sam Mendes, Nick Hornby in talks for live-action 'James and the Giant Peach'". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ "Sam Mendes in Early Talks to Direct 'Pinocchio' Live-Action Movie". Variety. 22 May 2017. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

Mendes will no longer direct the "James and the Giant Peach" remake for Disney, which he was attached to less than a year ago.

Bibliography

- French, Lawrence (April 1996). "James and the Giant Peach". Cinefantastique. pp. 7, 61. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- French, Lawrence (May 1996). "James and the Giant Peach". Cinefantastique. pp. 24–43. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

External links

- 1996 films

- Annecy Cristal for a Feature Film winners

- 1990s American animated films

- 1990s British films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s fantasy adventure films

- 1990s musical comedy films

- 1990s stop-motion animated films

- 1996 animated films

- 1996 children's films

- 1996 comedy films

- American children's animated adventure films

- American children's animated fantasy films

- American children's animated musical films

- American fantasy adventure films

- American fantasy comedy films

- American films with live action and animation

- Animated films about children

- Animated films about orphans

- American musical comedy films

- British animated fantasy films

- British children's animated films

- British children's fantasy films

- British fantasy adventure films

- British films with live action and animation

- British musical comedy films

- Animated films based on works by Roald Dahl

- Films directed by Henry Selick

- Films produced by Denise Di Novi

- Films produced by Tim Burton

- Films scored by Randy Newman

- Films using stop-motion animation

- Films set in 1948

- Films shot in London

- Films set in England

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in the 1940s

- Films with screenplays by Jonathan Roberts (writer)

- Films with screenplays by Karey Kirkpatrick

- Walt Disney Pictures animated films

- English-language musical comedy films

- English-language fantasy adventure films