Laodicea in Syria

This article may be in need of reorganization to comply with Wikipedia's layout guidelines. (May 2021) |

35°31′08″N 35°46′36″E / 35.51892275°N 35.7766297°E

Laodicea (Ancient Greek: Λαοδίκεια) was a port city and important colonia of the Roman Empire in ancient Syria,[1] near the modern city of Latakia. It was also called Laodicea in Syria or Laodicea ad mare. Under Septimius Severus, it was the capital of Roman Syria, and of the Eastern Roman province of Theodorias from 528 to 637 AD.

History

[edit]

The Phoenician city of Ramitha was located in the coastal area where the modern port of Latakia is, known to the Greeks as Leukê Aktê or "white coast". Laodicea got its name when was first founded in the fourth century BC under the rule of the Seleucid Empire: it was named by Seleucus I Nicator in honor of his mother, Laodice (Greek: Λαοδίκεια ἡ Πάραλος). The city was subsequently ruled by the Romans until the Arab conquest of that city in 636 AD.

The Roman Pompey the Great conquered the city from the Armenian king Tigranes the Great along with all of Syria in 64 BCE and later Julius Caesar declared the city "free polis". Some Roman merchants moved to live in the city under Augustus, but the city was always culturally "greek" influenced. The Romans made a "Pharum" at the port, that was renowned as one of the best of Ancient Levant; then created a Roman road from southern Anatolia toward Berytus and Damascus, that greatly improved the commerce through the port of Laodicea.

There are few remains of what was a rich and well-built town (Strab. 16.2.9): colonnades, a monumental arch, sarcophagi, all within the modern town. The sanctuaries, public baths, amphitheater, hippodrome, mentioned by ancient authors or by Greek inscriptions, and the rampart gates depicted on coins, have all disappeared...The town occupies a rocky promontory...Including the port, its area was ca. 220 ha...A wide avenue, bordered with porticos in Roman times, ran N-S across the town, from the tip of the peninsula to the gate where the road to Antioch started; perpendicular to this, three colonnaded streets ran from E to W. The one to the N was centered on the entry to the citadel on the high hill to the NE. The central one came from the E gate, where the Apamea road reached the city. The street today is occupied by the great souk, where there is still an alignment of 13 monolithic granite columns. A tetrapylon marked the crossing of this thoroughfare with the N-S avenue. The S street began at the port and ended to the E at the long steep hill to the SE, where a monumental four-way arch, erroneously called a tetrapylon, closed off the view. This arch consists of four semicircular arches, one on each side, supporting a stone cupola. Columns engaged in pilasters serve as buttresses at the corners of the four masonry moles. Not far away, inside a mosque, is the corner of a Corinthian peristyle, with capitals and entablature. Virtually nothing remains of the theater, which was built against the SE hill and whose cavea had a diameter of ca. 100 m. Princeton: Laodicea ad mare

The city enjoyed a huge economic prosperity thanks to the wine produced in the hills around the port and exported to all the empire. The city was famous because of the textile products.[citation needed] Herod, king of Judaea, constructed an aqueduct for the city.[2] Laodicea minted coins from an early Roman date, but the most famous are from Severian times.[3]

A sizable Jewish population lived in Laodicea during the first century.[4] During the First Jewish–Roman War, Legio VI Ferrata was stationed in the city, which served as its winter quarters, before being joined to a larger army assembled to quell the rebellion in neighboring Judaea.[2]

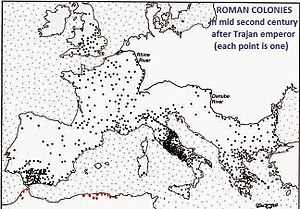

In 194 AD, during the reign of Severan dynasty, a third century imperial dynasty of Rome, the emperor Septimius Severus gave the title "Metropolis" to the city, and allowed the Ius Italicum (exemption from empire taxation) to Laodicea, that was later called a "Roman Colonia". Under Septimius Severus the city was fortified and was made for a few years the capital of Roman Syria: in this period Laodicea grew to be a city of nearly 40,000 inhabitants and had even an hippodrome.

Christianity was the main religion in the city after Constantine I and there were many bishops of Laodicea who participated in ecumenical councils, mainly during Byzantine times. The heretic Apollinarius was bishop of Laodicea in the 4th century, when the city was fully Christian but with a few remaining Jews.

An earthquake damaged the city in 494 AD[5] and successively Justinian I made Laodicea the capital of the Byzantine province of "Theodorias" in the early sixth century. Laodicea remained its capital for more than a century until the Arab conquest.

Bishops of Laodicea

[edit]Saint Paul visited Laodicea and converted the first Christians in the city. Slowly the bishops of Laodicea grew in importance but were always under the Patriarch of Antioch. The most important bishops were:

- Lucius of Cyrene (1st century), mentioned in Acts, traditionally considered the first bishop

- Thelymidres (fl. 250–251), bishop during the Decian persecution[6]

- Heliodorus, became bishop during the reign of Trebonianus Gallus (251–253)[6]

- Socrates (died. c. 264)[6]

- Eusebius (died c. 268), a native of Alexandria in Egypt[6]

- Anatolius (c. 268 – 282/283), a native of Alexandria in Egypt[6]

- Stephen, apostasized during the Diocletianic persecution (303–313)[6]

- Theodotus (303/313 – c. 335), an Arian[6]

- George (died 359), an Arian[6]

- After George there were two rival bishops in Laodicea:

- Pelagius (360–381/394), an Arian[6]

- Apollinarius (c. 360 – c. 392), founded the Apollinarians[6]

- Elpidius, bishop by 394, deposed in 404, restored in 416[6]

- Macarius (429-451)

- Maximus (around 458)

- Nicia

- Costantinus (510–518)

- Stephanus (553)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Burns, Ross (30 June 2009). Monuments of Syria: A Guide. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857714893. Retrieved 11 June 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Rogers, Guy MacLean (2021). For the Freedom of Zion: the Great Revolt of Jews against Romans, 66-74 CE. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 22, 162, 540. ISBN 978-0-300-24813-5.

- ^ "Featured Coin". Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "LAODICEA - JewishEncyclopedia.com". Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ Noelle Watson, ed. (1996), "Latakia", International Dictionary of Historic Places, Fitzroy Dearborn, ISBN 9781884964039

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Mark DelCogliano (2008), "The Eusebian Alliance: the Case of Theodotus of Laodicea" (PDF), Zeitschrift für antikes Christentum, 12 (2): 250–266, doi:10.1515/ZAC.2008.017, S2CID 170414251[dead link].

Bibliography

[edit]- Butcher, Kevin. Roman Syria and the Near East Getty Publications. Los Angeles, 2003 ISBN 0892367156 ([1])

- Ross Burns. Monuments of Syria: A Guide. Publisher I.B.Tauris. New York, 2009 ISBN 0857714899