Marcel Proust

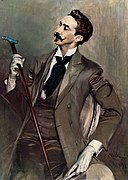

Marcel Proust | |

|---|---|

Proust in 1900 (photograph by Otto Wegener) | |

| Born | Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust 10 July 1871 |

| Died | 18 November 1922 (aged 51) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery |

| Education | Lycée Condorcet |

| Occupations |

|

| Notable work | In Search of Lost Time |

| Parent(s) | Adrien Achille Proust Jeanne Clémence Weil |

| Relatives | Robert Proust (brother) |

| Signature | |

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust (/pruːst/ PROOST;[1] French: [maʁsɛl pʁust]; 10 July 1871 – 18 November 1922) was a French novelist, literary critic, and essayist who wrote the monumental novel À la recherche du temps perdu (in French – translated in English as Remembrance of Things Past and more recently as In Search of Lost Time) which was published in seven volumes between 1913 and 1927. He is considered by critics and writers to be one of the most influential authors of the 20th century.[2][3]

Biography

[edit]Proust was born on 10 July 1871 at the home of his great-uncle in the Paris Borough of Auteuil (the south-western sector of the then-rustic 16th arrondissement), two months after the Treaty of Frankfurt formally ended the Franco-Prussian War. His birth took place at the very beginning of the French Third Republic,[4] during the violence that surrounded the suppression of the Paris Commune, and his childhood corresponded with the consolidation of the Republic. Much of In Search of Lost Time concerns the vast changes, most particularly the decline of the aristocracy and the rise of the middle classes, that occurred in France during the fin de siècle.

Proust's father, Adrien Proust, was a prominent French pathologist and epidemiologist, studying cholera in Europe and Asia. He wrote numerous articles and books on medicine and hygiene. Proust's mother, Jeanne Clémence (maiden name: Weil), was the daughter of a wealthy German–Jewish family from Alsace.[5] Literate and well-read, she demonstrated a well-developed sense of humour in her letters, and her command of the English language was sufficient to help with her son's translations of John Ruskin.[6] Proust was raised in his father's Catholic faith.[7] He was baptized on 5 August 1871 at the Church of Saint-Louis-d'Antin and later confirmed as a Catholic, but he never formally practised that faith. He later became an atheist and was something of a mystic.[8][9]

By the age of nine, Proust had had his first serious asthma attack, and thereafter he was considered a sickly child. Proust spent long holidays in the village of Illiers. This village, combined with recollections of his great-uncle's house in Auteuil, became the model for the fictional town of Combray, where some of the most important scenes of In Search of Lost Time take place. (Illiers was renamed Illiers-Combray in 1971 on the occasion of the Proust centenary celebrations.)

In 1882, at the age of eleven, Proust became a pupil at the Lycée Condorcet; however, his education was disrupted by his illness. Despite this, he excelled in literature, receiving an award in his final year. Thanks to his classmates, he was able to gain access to some of the salons of the upper bourgeoisie, providing him with copious material for In Search of Lost Time.[10]

In spite of his poor health, Proust served a year (1889–90) in the French army, stationed at Coligny Barracks in Orléans, an experience that provided a lengthy episode in The Guermantes' Way, part three of his novel. As a young man, Proust was a dilettante and a social climber whose aspirations as a writer were hampered by his lack of self-discipline. His reputation from this period, as a snob and an amateur, contributed to his later troubles with getting Swann's Way, the first part of his large-scale novel, published in 1913. At this time, he attended the salons of Mme Straus, widow of Georges Bizet and mother of Proust's childhood friend Jacques Bizet, of Madeleine Lemaire and of Mme Arman de Caillavet, one of the models for Madame Verdurin, and mother of his friend Gaston Arman de Caillavet, with whose fiancée (Jeanne Pouquet) he was in love. It is through Mme Arman de Caillavet, he made the acquaintance of Anatole France, her lover.

Proust had a close relationship with his mother. To appease his father, who insisted that he pursue a career, Proust obtained a volunteer position at Bibliothèque Mazarine in the summer of 1896. After exerting considerable effort, he obtained a sick leave that extended for several years until he was considered to have resigned. He never worked at his job, and he did not move from his parents' apartment until after both were dead.[6]

His life and family circle changed markedly between 1900 and 1905. In February 1903, Proust's brother, Robert Proust, married and left the family home. His father died in November of the same year.[11] Finally, and most crushingly, Proust's beloved mother died in September 1905. She left him a considerable inheritance. His health throughout this period continued to deteriorate.

Proust spent the last three years of his life mostly confined to his bedroom of his apartment 44 rue Hamelin[12][13] (in Chaillot), sleeping during the day and working at night to complete his novel.[14] He died of pneumonia and a pulmonary abscess in 1922. He was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.[15]

Personal life

[edit]Proust is known to have been homosexual; his sexuality and relationships with men are often discussed by his biographers.[16] Although his housekeeper, Céleste Albaret, denies this aspect of Proust's sexuality in her memoirs,[17] her denial runs contrary to the statements of many of Proust's friends and contemporaries, including his fellow writer André Gide[18] as well as his valet Ernest A. Forssgren.[19]

Proust never openly disclosed his homosexuality, though his family and close friends either knew or suspected it. In 1897, he fought a duel with writer Jean Lorrain, who publicly questioned the nature of Proust's relationship with his Proust's lover[20] Lucien Daudet; both duellists survived.[21] Despite Proust's public denials, his romantic relationship with composer Reynaldo Hahn[22] and his infatuation with his chauffeur and secretary, Alfred Agostinelli, are well documented.[23] On the night of 11 January 1918, Proust was one of the men identified by police in a raid on a male brothel run by Albert Le Cuziat.[24] Proust's friend Paul Morand openly teased Proust about his visits to male prostitutes. In his journal, Morand refers to Proust, as well as Gide, as "constantly hunting, never satiated by their adventures ... eternal prowlers, tireless sexual adventurers."[25]

The exact influence of Proust's sexuality on his writing is a topic of debate.[26] However, In Search of Lost Time discusses homosexuality at length and features several principal characters, both men and women, who are either homosexual or bisexual: the Baron de Charlus, Robert de Saint-Loup, Odette de Crécy, and Albertine Simonet.[27] Homosexuality also appears as a theme in Les plaisirs et les jours and his unfinished novel, Jean Santeuil.

Proust inherited much of his mother's political outlook, which was supportive of the French Third Republic and near the liberal centre of French politics.[28] In an 1892 article published in Le Banquet entitled "L'Irréligion d'État", Proust condemned extreme anti-clerical measures such as the expulsion of monks, observing that "one might just be surprised that the negation of religion should bring in its wake the same fanaticism, intolerance, and persecution as religion itself."[28][29] He argued that socialism posed a greater threat to society than the Church.[28] He was equally critical of the right, lambasting "the insanity of the conservatives," whom he deemed "as dumb and ungrateful as under Charles X," and referring to Pope Pius X's obstinacy as foolish.[30] Proust always rejected the bigoted and illiberal views harbored by many priests at the time, but believed that the most enlightened clerics could be just as progressive as the most enlightened secularists, and that both could serve the cause of "the advanced liberal Republic".[31] He approved of the more moderate stance taken in 1906 by Aristide Briand, whom he described as "admirable".[30]

Proust was among the earliest Dreyfusards, even attending Émile Zola's trial and proudly claiming to have been the one who asked Anatole France to sign the petition in support of Alfred Dreyfus's innocence.[32] In 1919, when representatives of the right-wing Action Française published a manifesto upholding French colonialism and the Catholic Church as the embodiment of civilised values, Proust rejected their nationalistic and chauvinistic views in favor of a liberal pluralist vision which acknowledged Christianity's cultural legacy in France.[28] Julien Benda commended Proust in La Trahison des clercs as a writer who distinguished himself from his generation by avoiding the twin traps of nationalism and class sectarianism.[28]

Proust was considered a hypochondriac by his doctors. His correspondence provides some clues on his symptoms.[clarification needed] According to Yellowlees Douglas, Proust suffered from the vascular subtype of Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome.[33]

Early writing

[edit]Proust was involved in writing and publishing from an early age. In addition to the literary magazines with which he was associated, and in which he published while at school (La Revue verte and La Revue lilas), from 1890 to 1891 he published a regular society column in the journal Le Mensuel.[6] In 1892, he was involved in founding a literary review called Le Banquet (also the French title of Plato's Symposium), and throughout the next several years Proust published small pieces regularly in this journal and in the prestigious La Revue Blanche.

In 1896 Les plaisirs et les jours, a compendium of many of these early pieces, was published. The book included a foreword by Anatole France, drawings by Mme Lemaire in whose salon Proust was a frequent guest, and who inspired Proust's Mme Verdurin. She invited him and Reynaldo Hahn to her château de Réveillon (the model for Mme Verdurin's La Raspelière) in summer 1894, and for three weeks in 1895. This book was so sumptuously produced that it cost twice the normal price of a book its size.[citation needed]

That year Proust also began working on a novel, which was eventually published in 1952 and titled Jean Santeuil by his posthumous editors. Many of the themes later developed in In Search of Lost Time find their first articulation in this unfinished work, including the enigma of memory and the necessity of reflection; several sections of In Search of Lost Time can be read in the first draft in Jean Santeuil. The portrait of the parents in Jean Santeuil is quite harsh, in marked contrast to the adoration with which the parents are painted in Proust's masterpiece. Following the poor reception of Les Plaisirs et les Jours, and internal troubles with resolving the plot, Proust gradually abandoned Jean Santeuil in 1897 and stopped work on it entirely by 1899.

Beginning in 1895 Proust spent several years reading Thomas Carlyle, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and John Ruskin. Through this reading, he refined his theories of art and the role of the artist in society. Also, in Time Regained Proust's universal protagonist recalls having translated Ruskin's Sesame and Lilies. The artist's responsibility is to confront the appearance of nature, deduce its essence and retell or explain that essence in the work of art. Ruskin's view of artistic production was central to this conception, and Ruskin's work was so important to Proust that he claimed to know "by heart" several of Ruskin's books, including The Seven Lamps of Architecture, The Bible of Amiens, and Praeterita.[6]

Proust set out to translate two of Ruskin's works into French, but was hampered by an imperfect command of English. To compensate for this he made his translations a group affair: sketched out by his mother, the drafts were first revised by Proust, then by Marie Nordlinger, the English cousin of his friend and sometime lover[22] Reynaldo Hahn, then finally polished by Proust. Questioned about his method by an editor, Proust responded, "I don't claim to know English; I claim to know Ruskin".[6][34] The Bible of Amiens, with Proust's extended introduction, was published in French in 1904. Both the translation and the introduction were well-reviewed; Henri Bergson called Proust's introduction "an important contribution to the psychology of Ruskin", and had similar praise for the translation.[6] At the time of this publication, Proust was already translating Ruskin's Sesame and Lilies, which he completed in June 1905, just before his mother's death, and published in 1906. Literary historians and critics have ascertained that, apart from Ruskin, Proust's chief literary influences included Saint-Simon, Montaigne, Stendhal, Flaubert, George Eliot, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, and Leo Tolstoy.[citation needed]

In Proust’s 1904 article "La mort des cathédrales" (The Death of Cathedrals) published in Le Figaro, Proust called Gothic cathedrals “probably the highest, and unquestionably the most original expression of French genius”.[35]

1908 was an important year for Proust's development as a writer. During the first part of the year he published in various journals pastiches of other writers. These exercises in imitation may have allowed Proust to solidify his own style. In addition, in the spring and summer of the year Proust began work on several different fragments of writing that would later coalesce under the working title of Contre Sainte-Beuve. Proust described his efforts in a letter to a friend: "I have in progress: a study on the nobility, a Parisian novel, an essay on Sainte-Beuve and Flaubert, an essay on women, an essay on pederasty (not easy to publish), a study on stained-glass windows, a study on tombstones, a study on the novel".[6]

From these disparate fragments Proust began to shape a novel on which he worked continually during this period. The rough outline of the work centred on a first-person narrator, unable to sleep, who during the night remembers waiting as a child for his mother to come to him in the morning. The novel was to have ended with a critical examination of Sainte-Beuve and a refutation of his theory that biography was the most important tool for understanding an artist's work. Present in the unfinished manuscript notebooks are many elements that correspond to parts of the Recherche, in particular, to the "Combray" and "Swann in Love" sections of Volume 1, and to the final section of Volume 7. Trouble with finding a publisher, as well as a gradually changing conception of his novel, led Proust to shift work to a substantially different project that still contained many of the same themes and elements. By 1910 he was at work on À la recherche du temps perdu.

In Search of Lost Time

[edit]Begun in 1909, when Proust was 38 years old, À la recherche du temps perdu consists of seven volumes totaling around 3,200 pages (about 4,300 in The Modern Library's translation) and featuring more than 2,000 characters. Graham Greene called Proust the "greatest novelist of the twentieth century, just as Tolstoy was of the nineteenth"[36] and W. Somerset Maugham called the novel the "greatest fiction to date".[37] André Gide was initially not so taken with his work. The first volume was refused by the publisher Gallimard on Gide's advice. He later wrote to Proust apologizing for his part in the refusal and calling it one of the most serious mistakes of his life.[38] Finally, the book was published at the author's expense by Grasset and Proust paid critics to speak favorably about it.[39]

Proust died before he was able to complete his revision of the drafts and proofs of the final volumes, the last three of which were published posthumously and edited by his brother Robert. The book was translated into English by C. K. Scott Moncrieff, appearing under the title Remembrance of Things Past between 1922 and 1931. Scott Moncrieff translated volumes one through six of the seven volumes, dying before completing the last. This last volume was rendered by other translators at different times. When Scott Moncrieff's translation was later revised (first by Terence Kilmartin, then by D. J. Enright) the title of the novel was changed to the more literal In Search of Lost Time.

In 1995, Penguin undertook a fresh translation of the book by editor Christopher Prendergast and seven translators in three countries, based on the latest, most complete and authoritative French text. Its six volumes, comprising Proust's seven, were published in Britain under the Allen Lane imprint in 2002.

In 2023, Oxford University Press started releasing a new translation of the book by editors Brian Nelson and Adam Watt and five other translators. It will be published in seven volumes under the Oxford World's Classics imprint.

Gallery

[edit]-

Jean Béraud, La Sortie du lycée Condorcet

-

102 Boulevard Haussmann, Paris, where Marcel Proust lived from 1907 to 1919

-

Robert de Montesquiou, the main inspiration for Baron de Charlus in À la recherche du temps perdu

-

Grave of Marcel Proust at Père Lachaise Cemetery

Bibliography

[edit]Novels

[edit]- In Search of Lost Time (À la recherche du temps perdu published in seven volumes, previously translated as Remembrance of Things Past) (1913–1927)

- Swann's Way (Du côté de chez Swann, sometimes translated as The Way by Swann's) (1913)

- In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower (À l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs, also translated as Within a Budding Grove) (1919)

- The Guermantes Way (Le Côté de Guermantes originally published in two volumes) (1920–1921)

- Sodom and Gomorrah (Sodome et Gomorrhe originally published in two volumes, sometimes translated as Cities of the Plain) (1921–1922)

- The Prisoner (La Prisonnière, also translated as The Captive) (1923)

- The Fugitive (Albertine disparue, also titled La Fugitive, sometimes translated as The Sweet Cheat Gone or Albertine Gone) (1925)

- Time Regained (Le Temps retrouvé, also translated as Finding Time Again and The Past Recaptured) translated by C. K. Scott Moncrieff (1927)

- Jean Santeuil (1896–1900, unfinished novel in three volumes published posthumously – 1952)

Short story collections

[edit]- Early Stories (short stories published posthumously)

- Pleasures and Days (Les plaisirs et les jours; illustrations by Madeleine Lemaire, preface by Anatole France, and four piano works by Reynaldo Hahn) (1896)

Non-fiction

[edit]- Pastiches, or The Lemoine Affair (Pastiches et mélanges – a collection) (1919)

- Against Sainte-Beuve (Contre Sainte-Beuve: suivi de Nouveaux mélanges) (published posthumously 1954)

Translations of John Ruskin

[edit]- La Bible d'Amiens (translation of The Bible of Amiens) (1896)

- Sésame et les lys: des trésors des rois, des jardins des reines (translation of Sesame and Lilies) (1906)

See also

[edit]- 102 Boulevard Haussmann, a BBC production set in 1916 about Proust

- Albertine, a novel based on a character in À la recherche du temps perdu by Jacqueline Rose (London, 2001)

- Céleste, a German film dramatising part of Proust's life, seen from the viewpoint of his housekeeper Céleste Albaret

- Involuntary memory

- Le Temps Retrouvé, d'après l'œuvre de Marcel Proust (Time Regained), film by director Raúl Ruiz, 1999

- Mme Proust and the Kosher Kitchen, a novel by Kate Taylor that includes a fictional diary written by Proust's mother

- Proust, an essay by Samuel Beckett

- Proust Questionnaire

- Swann in Love, film by the director Volker Schlöndorff, 1984

- La captive, film by the director Chantal Akerman, 2000

- Little Miss Sunshine, an American road-trip tragicomedy where Steve Carell plays an ex-Proust professor.

References

[edit]- ^ "Proust" Archived 22 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Harold Bloom, Genius, pp. 191–225.

- ^ "Marcel Proust". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Ellison, David (2010). A Reader's Guide to Proust's 'In Search of Lost Time'. p. 8.

- ^ Massie, Allan. "Madame Proust: A Biography By Evelyne Bloch-Dano, translated by Alice Kaplan". Literary Review. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tadié, J-Y. (Euan Cameron, trans.) Marcel Proust: A life. New York: Penguin Putnam, 2000.

- ^ NYSL TRAVELS: Paris: Proust's Time Regained Archived 27 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Edmund White (2009). Marcel Proust: A Life. Penguin. ISBN 9780143114987. "Marcel Proust was the son of a Christian father and a Jewish mother. He himself was baptized (on August 5, 1871, at the church of Saint-Louis d'Antin) and later confirmed as a Roman Catholic, but he never practised that faith and as an adult could best be described as a mystical atheist, someone imbued with spirituality who nonetheless did not believe in a personal God, much less in a savior."

- ^ Proust, Marcel (1999). The Oxford dictionary of quotations. Oxford University Press. p. 594. ISBN 978-0-19-860173-9. "...the highest praise of God consists in the denial of him by the atheist who finds creation so perfect that it can dispense with a creator."

- ^ Painter, George D. (1959) Marcel Proust: a biography; Vols. 1 & 2. London: Chatto & Windus

- ^ Carter (2002)

- ^ "Mort de Marcel Proust". 4 January 2022. Archived from the original on 18 March 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ Gilberto Schwartsmann, Emmanuel Tugny, Pascale Privey (2022). La Maîtresse de Proust. p. 193.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Marcel Proust: Revolt against the Tyranny of Time. Harry Slochower .The Sewanee Review, 1943.

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 38123-38124). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Painter (1959), White (1998), Tadié (2000), Carter (2002 and 2006)

- ^ Albaret (2003)

- ^ Harris (2002)

- ^ Forssgren (2006)

- ^ White, Edmund. "Marcel Proust". Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ Hall, Sean Charles (12 February 2012). "Dueling Dandies: How Men Of Style Displayed a Blasé Demeanor In the Face of Death". Dandyism. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2024.

- ^ a b Carter, William C. (2006), Proust in Love, YaleUniversity Press, pp. 31–35, ISBN 0-300-10812-5

- ^ Whitaker, Rick (1 June 2000). "Proust's dearest pleasures: The best of a slew of recent biographies points to the author's conscious self-closeting". Salon. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ Murat, Laure (May 2005). "Proust, Marcel, 46 ans, rentier: Un individu 'aux allures de pédéraste' fiche à la police", La Revue littéraire 14: 82–93; Carter (2006)

- ^ Morand, Paul. Journal inutile, tome 2: 1973 – 1976, ed. Laurent Boyer and Véronique Boyer. Paris: Gallimard, 2001; Carter (2006)

- ^ Sedgwick (1992); O'Brien (1949)

- ^ Sedgwick (1992); Ladenson (1999); Bersani (2013)

- ^ a b c d e Hughes, Edward J. (2011). Proust, Class, and Nation. Oxford University Press. pp. 19–46.

- ^ Carter, William C. (2013). Marcel Proust: A Life, with a New Preface by the Author. Yale University Press. p. 346.

- ^ a b Watson, D. R. (1968). "Sixteen Letters of Marcel Proust to Joseph Reinach". The Modern Language Review. 63 (3): 587–599. doi:10.2307/3722199. JSTOR 3722199.

- ^ Sprinker, Michael (1998). History and Ideology in Proust: A la Recherche Du Temps Perdu and the Third French Republic. Verso. pp. 45–46.

- ^ Bales, Richard (2001). The Cambridge Companion to Proust. Cambridge University Press. p. 21.

- ^ Douglas, Yellowlees (1 May 2016). "The real malady of Marcel Proust and what it reveals about diagnostic errors in medicine". Medical Hypotheses. 90: 14–18. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2016.02.024. ISSN 1532-2777. PMID 27063078. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ Karlin, Daniel (2005) Proust's English; p. 36

- ^ "RORATE CÆLI: THE DEATH OF CATHEDRALS – and the Rites for which they were built – by Marcel Proust (Full English translation)". Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ White, Edmund (1999). Marcel Proust, a life. Penguin. p. 2. ISBN 9780143114987.

- ^ Alexander, Patrick (2009). Marcel Proust's Search for Lost Time: A Reader's Guide to The Remembrance of Things Past. Knopf Doubleday. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-307-47560-2. Archived from the original on 27 May 2024. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Tadié, J-Y. (Euan Cameron, trans.) Marcel Proust: A Life. p. 611

- ^ « Marcel Proust paid for reviews praising his work to go into newspapers », Agence France-Presse in The Guardian, 28 septembre 2017, online Archived 27 May 2024 at the Wayback Machine.

Further reading

[edit]- Aciman, André (2004), The Proust Project. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Adams, William Howard; Paul Nadar (photo.), A Proust Souvenir. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson (1984)

- Adorno, Theodor (1967), Prisms. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press

- Adorno, Theodor, "Short Commentaries on Proust," Notes to Literature, trans. S. Weber-Nicholsen (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991).

- Albaret, Céleste (Barbara Bray, trans.) (2003), Monsieur Proust. New York: New York Review Books

- Beckett, Samuel, Proust, London: Calder

- Benjamin, Walter, "The Image of Proust," Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969); pp. 201–215.

- Bernard, Anne-Marie (2002), The World of Proust, as seen by Paul Nadar. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press

- Bersani, Leo, Marcel Proust: The Fictions of Life and of Art (2013), Oxford: Oxford U. Press

- Bowie, Malcolm, Proust Among the Stars, London: Harper Collins

- Capetanakis, Demetrios, "A Lecture on Proust", in Demetrios Capetanakis A Greek Poet in England (1947)

- Carter, William C. (2002), Marcel Proust: A Life. New Haven: Yale University Press

- Carter, William C. (2006), Proust in Love. New Haven: Yale University Press

- Chardin, Philippe (2006), Proust ou le bonheur du petit personnage qui compare. Paris: Honoré Champion

- Chardin, Philippe et alii (2010), Originalités proustiennes. Paris: Kimé

- Compagnon, Antoine, Proust Between Two Centuries, Columbia U. Press

- Czapski, Józef (2018) Lost Time. Lectures on Proust in a Soviet Prison Camp. New York: New York Review Books. 90 pp. ISBN 978-1-68137-258-7

- Davenport-Hines, Richard (2006), A Night at the Majestic. London: Faber and Faber ISBN 9780571220090

- De Botton, Alain (1998), How Proust Can Change Your Life. New York: Vintage Books

- Deleuze, Gilles (2004), Proust and Signs: the complete text. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

- De Man, Paul (1979), Allegories of Reading: Figural Language in Rousseau, Nietzsche, Rilke, and Proust ISBN 0-300-02845-8

- Descombes, Vincent, Proust: Philosophy of the Novel. Stanford, CA: Stanford U. Press

- Forssgren, Ernest A. (William C. Carter, ed.) (2006), The Memoirs of Ernest A. Forssgren: Proust's Swedish Valet. New Haven: Yale University Press

- Foschini, Lorenza, Proust's Overcoat: The True Story of One Man's Passion for All Things Proust. London: Portobello Books (2010)

- Genette, Gérard, Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method. Ithaca, NY: Cornell U. Press

- Gracq, Julien, "Proust Considered as An End Point," in Reading Writing (New York: Turtle Point Press,), 113–130.

- Green, F. C. The Mind of Proust (1949)

- Harris, Frederick J. (2002), Friend and Foe: Marcel Proust and André Gide. Lanham: University Press of America

- Hayman, Ronald (1990), Proust. A Biography. London: William Heinemann

- Hillerin, Laure La comtesse Greffulhe, L'ombre des Guermantes Archived 19 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Paris, Flammarion, 2014. Part V, La Chambre Noire des Guermantes. About Marcel Proust and comtesse Greffulhe's relationship, and the key role she played in the genesis of La Recherche.

- Karlin, Daniel (2005), Proust's English. Oxford: Oxford University Press ISBN 978-0199256884

- Kristeva, Julia, Time and Sense. Proust and the Experience of Literature. New York: Columbia U. Press, 1996

- Ladenson, Elisabeth (1991), Proust's Lesbianism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell U. Press

- Landy, Joshua, Philosophy as Fiction: Self, Deception, and Knowledge in Proust. Oxford: Oxford U. Press

- O'Brien, Justin. "Albertine the Ambiguous: Notes on Proust's Transposition of Sexes", PMLA 64: 933–52, 1949

- Painter, George D. (1959), Marcel Proust: A Biography; Vols. 1 & 2. London: Chatto & Windus

- Poulet, Georges, Proustian Space. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins U. Press

- Prendergast, Christopher Mirages and Mad Beliefs: Proust the Skeptic Archived 15 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 9780691155203

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky (1992), "Epistemology of the Closet". Berkeley: University of California Press

- Shattuck, Roger (1963), Proust's Binoculars: a study of memory, time, and recognition in "À la recherche du temps perdu". New York: Random House

- Spitzer, Leo, "Proust's Style," [1928] in Essays in Stylistics (Princeton, Princeton U. P., 1948).

- Shattuck, Roger (2000), Proust's Way: a field guide to "In Search of Lost Time". New York: W. W. Norton

- Tadié, Jean-Yves (2000), Marcel Proust: A Life. New York: Viking

- White, Edmund (1998), Marcel Proust. New York: Viking Books

External links

[edit]- BBC audio file. In Our Time discussion, Radio 4.

- The Kolb-Proust Archive for Research. University of Illinois.

- Works by Marcel Proust in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Marcel Proust at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Marcel Proust at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by Marcel Proust at Project Gutenberg Australia

- Works by or about Marcel Proust at the Internet Archive

- Works by Marcel Proust at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Marcel Proust at Open Library

- The Album of Marcel Proust, Marcel Proust receives a tribute in this album of "recomposed photographs".

- Rothstein, Edward (14 February 2013). "Swann's Way Exhibited at The Morgan Library". The New York Times.

- "Why Proust? And Why Now?". The New York Times. 13 April 2000. – Essay on the lasting relevance of Proust and his work.

- University of Adelaide Library French text of volumes 1–4 and the complete novel in English translation

- Marcel Proust

- 1871 births

- 1922 deaths

- 19th-century atheists

- 19th-century French essayists

- 19th-century French LGBTQ people

- 19th-century French non-fiction writers

- 19th-century French philosophers

- 19th-century French short story writers

- 19th-century French translators

- 19th-century mystics

- 20th-century atheists

- 20th-century French essayists

- 20th-century French LGBTQ people

- 20th-century French novelists

- 20th-century French philosophers

- 20th-century French short story writers

- 20th-century French translators

- 20th-century mystics

- Aphorists

- Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery

- Conversationalists

- Deaths from pneumonia in France

- Dreyfusards

- Former Roman Catholics

- French atheists

- French duellists

- French essayists

- French gay writers

- French LGBTQ novelists

- French literary critics

- French literary theorists

- French male non-fiction writers

- French people of German-Jewish descent

- French psychological fiction writers

- French Roman Catholic writers

- French short story writers

- French translators

- People with hypochondriasis

- LGBTQ Roman Catholics

- Lycée Condorcet alumni

- Modernist writers

- French philosophers of art

- Philosophers of literature

- Prix Goncourt winners

- Writers from Paris