We're Only in It for the Money

| We're Only in It for the Money | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

original issue cover | ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | March 4, 1968 | |||

| Recorded | March 6, 1967 July – October 8, 1967[1] | |||

| Studio | ||||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 39:15 | |||

| Label | Verve | |||

| Producer | Frank Zappa | |||

| Frank Zappa chronology | ||||

| ||||

| The Mothers of Invention chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from We're Only in It for the Money | ||||

| ||||

We're Only in It for the Money is the third album by American rock band the Mothers of Invention, released on March 4, 1968, by Verve Records. As with the band's first two efforts, it is a concept album, and satirizes left- and right-wing politics, particularly the hippie subculture, as well as the Beatles' album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. It was conceived as part of a project called No Commercial Potential, which produced three other albums: Lumpy Gravy, Cruising with Ruben & the Jets, and Uncle Meat.

We're Only in It for the Money encompasses rock, experimental music, and psychedelic rock, with orchestral segments deriving from the recording sessions for Lumpy Gravy, which was previously issued by Capitol Records as a solo instrumental album by bandleader/guitarist Frank Zappa and was subsequently reedited by Zappa and released by Verve; the reedited Lumpy Gravy was produced simultaneously with We're Only in It for the Money. We're Only in It for the Money is the first "phase" of a conceptual continuity, which continued with the reedited Lumpy Gravy and concluded with Zappa's final album Civilization Phaze III (1994). In 2005, We're Only in It for the Money was selected for preservation in the National Recording Registry by the United States' Library of Congress, who deemed it "culturally, historically, and aesthetically significant" and "a scathing satire on hippiedom and America's reactions to it".

Background

[edit]While filming Uncle Meat, Frank Zappa recorded in New York City for a project called No Commercial Potential, which ended up producing four albums: We're Only in It for the Money; a revised version of Zappa's solo album Lumpy Gravy; Cruising with Ruben & the Jets; and Uncle Meat, which served as the soundtrack to the film of the same name, which finally saw a release in 1987, albeit in incomplete form.[5]

Zappa stated, "It's all one album. All the material in the albums is organically related and if I had all the master tapes and I could take a razor blade and cut them apart and put it together again in a different order it still would make one piece of music you can listen to. Then I could take that razor blade and cut it apart and reassemble it a different way, and it still would make sense. I could do this twenty ways. The material is definitely related."[5]

As the recording sessions continued, the Beatles released their acclaimed album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. In response to the album's release, Zappa decided to change the album's concept to parody the Beatles album, because he felt that the Beatles were insincere and "only in it for the money".[6] The Beatles were targeted as a symbol of Zappa's objections to the corporatization of youth culture, and the album served as a criticism of them and psychedelic rock as a whole.[6]

Recording

[edit]Recording for We're Only in it for the Money began on March 6, 1967, with the basic tracking of "Who Needs the Peace Corps?" at TTG Studios which was then under the title of "Fillmore". The working title was inspired by a series of performance the Mothers of Invention held at the Fillmore Auditorium, finishing a day prior to the recording session. Zappa would then inaugurate a three-day recording stint at Capital Studios to record Lumpy Gravy from March 14-16, 1967.[7] The band returned to New York in the following week, where Zappa became acquainted to then Cream guitarist Eric Clapton during an acoustic guitar led jam at his home. The band subsequently spent from April to June rehearsing and gigging locally in support of their previous album Absolutely Free, which released on May 26, 1967.[8] Popular contemporaries such as guitarist Jimi Hendrix,[9] and singer-songwriter Essra Mohawk,[10] joined the Mothers of Invention during their New York shows.

In July, band member Ray Collins had left the Mothers before the New York recording sessions took place, but later rejoined when the band was recording the doo-wop songs that formed the album Cruisin' with Ruben & the Jets.[6] Gary Kellgren was hired as an engineer for the project, and subsequently wound up delivering whispered pieces of dialogue that linked segments of We're Only in It for the Money.[11] During the recording sessions, Verve requested that Zappa remove a verse from the song "Mother People". Zappa complied, but reversed the recording and included the backwards verse as part of the dialogue track "Hot Poop", concluding the album's first side,[12] but this would be removed by Verve themselves on subsequent represses of their own. Also censored on all copies was the Lenny Bruce reference in "Harry, You're A Beast",[13] and a spoken segment of "Concentration Moon" in which Kellgren called the Velvet Underground "as shitty a group as Frank Zappa's group".[14]

Primary recording sessions ran from July until September 1967 at Mayfair Studios in New York. During this period of work on the album, the band recorded at a continuous rate, only taking breaks on the weekends.[15] While the Jimi Hendrix Experience occupied Mayfair Studios on July 19 and 20, to record "The Stars That Play with Laughing Sam's Dice", the band worked on and executed ideas for the cover art for We're Only in it for the Money. Hendrix would make an appearance in the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band mock cover, blending in with the cardboard cutouts of other major figures.[16] Weekday work was only halted again on August 4, when Bob Dylan booked the studio to mix and press an acetate disc of "Too Much Of Nothing".[15][17] A majority of the basic tracks would be finished in August, and September was spent mostly overdubbing onto the basic recordings.[7] On September 4,[18] the Velvet Underground, who the Mothers of Invention then detested, entered the studio's second recording space with Tom Wilson, the band's previous producer, to record their sophomore album, White Light/White Heat. Both bands did however co-operate in the studio, and Zappa even suggested to Velvet Underground front-man Lou Reed that he record himself stabbing a cantaloupe with a wrench in the band's song "The Gift".[19] The Mothers of Invention halted work on September 22 to pursue what is considered to be their first European tour,[8] before returning to Apostolic Studios, also in New York, from October 3-8 in order to finish the album off, with final overdubs and mixing occurring.[7]

While recording We're Only in It for the Money, Zappa discovered that the strings of Apostolic Studios' grand piano would resonate if a person spoke near those strings. The "piano people" experiment involved Zappa having various speakers improvise dialogue using topics offered by Zappa. Various people contributed to these sessions, including Eric Clapton, Rod Stewart and Tim Buckley, who Zappa became familiar with after a concert in December 1966.[20][21] The "piano people" voices primarily consisted of Motorhead Sherwood, Roy Estrada, Spider Barbour, All-Night John (the manager of the studio) and Louis Cuneo, who was noted for his laugh, which sounded like a "psychotic turkey".[14]

During the production, Zappa experimented with recording and editing techniques which produced unusual textures and musique concrète compositions; the album featured abbreviated songs interrupted by segments of dialogue and unrelated music which changed the continuity of the album.[22] Segments of orchestral music included on the album came from a solo orchestral album by Zappa previously released by Capitol Records under the title Lumpy Gravy in 1967.[11] MGM claimed that Zappa was under contractual obligation to record for them, and subsequently Zappa re-edited Lumpy Gravy, releasing a drastically different version on Verve Records, after the release of We're Only in It for the Money. The artwork of Lumpy Gravy identified it as "phase 2 of We're Only in It for the Money", while We're Only in It for the Money was identified in its artwork as "phase one of Lumpy Gravy", alluding to the conceptual continuity of the two albums.[11]

For some pressings of the album, MGM censored several tracks without Zappa's knowledge, involvement or permission.[11][23] On the song "Absolutely Free", the line "I don't do publicity balling for you anymore" was edited by MGM to remove the word "balling", changing the meaning of the sentence.[11] Additionally, on "Let's Make the Water Turn Black", the line "and I still remember Mama, with her apron and her pad, feeding all the boys at Ed's Cafe" was removed.[23] Zappa later learned that this line was censored because an MGM executive thought that the word "pad" referred to a sanitary napkin, rather than a waitress's order pad.[23] The Kellgren dialogue segment in "Concentration Moon" was also re-edited, making it seem that he was calling the Velvet Underground "Frank Zappa's group." Zappa later declined to accept an award for the album upon being made aware of the censorship, stating "I prefer that the award be presented to the guy who modified this record, because what you're hearing is more reflective of his work than mine."[23]

Themes

[edit]In his lyrics for We're Only in It for the Money, Zappa speaks as a voice for "the freaks—imaginative outsiders who didn't fit comfortably into any group", according to AllMusic writer Steve Huey.[22] Subsequently, the album satirizes hippie culture and left-wing politics, as well as targeting right-wing politics, describing both political sides as "prisoners of the same narrow-minded, superficial phoniness."[12][22][24]

Zappa later stated in 1978, "hippies were pretty stupid. ... the people involved in [youth] processes ... are very sensitive to criticism. They always take themselves too seriously. So anybody who impugns the process, whether it's a peace march or love beads or whatever it is – that person is the enemy and must be dealt with severely. So we came under a lot of criticism, because we dared to suggest that perhaps what was going on was really stupid."[6]

Another element of the album's lyrical content came from the Los Angeles Police Department's harassment and arrests of young rock fans, which made it difficult for the band to perform on the West Coast, leading the band to move to New York City for better financial opportunities.[6] Additionally, Zappa made reference to comedian Lenny Bruce; the song "Harry, You're A Beast" quotes Bruce's routine "To Is A Preposition, Come Is A Verb".[13]

The song "Flower Punk" parodies the garage rock staple "Hey Joe", and depicts a youth going to San Francisco to become a flower child and join a psychedelic rock band.[25] Additionally, the track makes a reference to "Wild Thing", one of the songs that defined the counterculture of that period. The rhythmic pattern of "Flower Punk" is complex, consisting of 4 bars of a fast 5 (2–3), followed by 4 bars of 7 (2–2–3).[26]

Packaging

[edit]

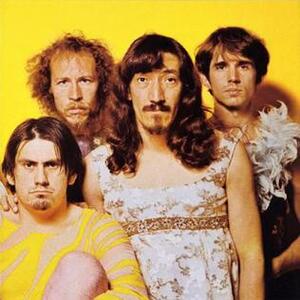

Zappa's art director Cal Schenkel and Jerry Schatzberg photographed a collage for the album cover, which parodied the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Zappa spent US$4,000 (equivalent to $35,000 in 2023) on the photo shoot, which he stated was "a direct negative" of the Sgt. Pepper album cover. "[Sgt. Pepper] had blue skies ... we had a thunderstorm."[6] Jimi Hendrix, a friend of Zappa, took part in the photo shoot.[6]

Zappa phoned Paul McCartney, seeking permission for the parody. McCartney told him that it was an issue for business managers,[6][11][14] but Zappa responded that the artists themselves were supposed to tell their business managers what to do.[11][14] Nevertheless, Capitol objected, and the album's release was delayed for five months.[11][27] Verve decided to package the album with inverted cover artwork, placing the parody cover as interior artwork (and the intended interior artwork as the main sleeve) out of fear of legal action.[6][12] Zappa was angered over the decision; Schenkel felt that the Sgt. Pepper parody "was a stronger image" than the final released cover.[6] In recent years, the album has been reissued with the intended front cover.

Release

[edit]The album was released on March 4, 1968, by Verve Records. It peaked at number 30 on the Billboard 200.

In 1984, Zappa prepared a remix of the album for its compact disc reissue and the vinyl box set The Old Masters I. The remix reinstated audio that had been censored by Verve, as well as the original "Mother People" verse.[14] It also featured new rhythm tracks recorded by bassist Arthur Barrow and drummer Chad Wackerman. Zappa would later do the same with Cruising with Ruben & the Jets, stating "The master tapes for Ruben and the Jets were in better shape, but since I liked the results on We're Only in It for the Money, I decided to do it on Ruben too. But those are the only two albums on which the original performances were replaced. I thought the important thing was the material itself."[5]

Lumpy Gravy was also remixed by Zappa, but not released at the time.[6] After the remixing was announced, a $13 million lawsuit was filed against Zappa by Jimmy Carl Black, Bunk Gardner and Don Preston, who were later joined by Ray Collins, Art Tripp and Motorhead Sherwood, increasing the claim to $16.4 million, stating that they had received no royalties from Zappa since 1969.[5]

Zappa would later prepare a CD of the original stereo mix for release by Rykodisc in 1995. Unlike the remix, this retained the censorship applied to "Concentration Moon," "Harry You're a Beast" and "Mother People" on the original releases.[28]

The audio documentary box set The Lumpy Money Project/Object chronicles the production of We're Only in It for the Money, including the orchestral version of Lumpy Gravy, a 1968 mono mix of We're Only in It for the Money and 1984 remixes of We're Only in It for the Money and the reedited Lumpy Gravy album, as well as additional material from the original recording sessions.

Reception and legacy

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| The Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A[30] |

| The Great Rock Bible | 8.5/10[31] |

| MusicHound Rock | |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Tom Hull | B−[35] |

| The Village Voice | A[36] |

Barret Hansen praised the album in an April 1968 review for Rolling Stone.[6] He felt it was the most "advanced" rock album released up to that date, though not necessarily the "best"; he compared Zappa with the Beatles, and felt that the wit and sharpness of Zappa's lyrics was more intelligent, but unless one were to adopt a utilitarian view, he would not deny the beauty of the Beatles' music. He concluded that while the initial listening may be significantly profound, due to the reliance on shock, subsequent listening may be reduced in value; and he returns to a comparison with the Beatles, in which he feels that Zappa has the greater musical genius, but is less comfortable to listen to.[38]

AllMusic writer Steve Huey wrote, "the music reveals itself as exceptionally strong, and Zappa's politics and satirical instinct have rarely been so focused and relevant, making We're Only in It for the Money quite possibly his greatest achievement."[22] Robert Christgau gave the album an A, writing, "With bohemia permanent and changed utterly, this early attack on its massification hasn't so much dated as found its context. Cheap sarcasm is forever."[36] In 2012, Uncut described the album as a "satirical psych-rock gem".[39]

It was voted number 343 in the third edition of Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums (2000).[40] As of 2015, the album was ranked number 297 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.[41] Additionally, Rolling Stone ranked the album number 77 in its August 1987 article, "The Top 100: The Best Albums of the Last Twenty Years".[42] It is also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die along with the Mothers' first release, Freak Out!.[43]

In 2005, the U.S. National Recording Preservation Board included We're Only in It for the Money in the National Recording Registry, calling it "culturally, historically, and aesthetically significant" and "a scathing satire on hippiedom and America's reactions to it".[44]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks are written by Frank Zappa

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Are You Hung Up?" | 1:23 |

| 2. | "Who Needs the Peace Corps?" | 2:34 |

| 3. | "Concentration Moon" | 2:22 |

| 4. | "Mom & Dad" | 2:16 |

| 5. | "Telephone Conversation" (included in "Bow Tie Daddy" on the original LP) | 0:48 |

| 6. | "Bow Tie Daddy" | 0:33 |

| 7. | "Harry, You're a Beast" | 1:22 |

| 8. | "What's the Ugliest Part of Your Body?" | 1:03 |

| 9. | "Absolutely Free" | 3:24 |

| 10. | "Flower Punk" | 3:03 |

| 11. | "Hot Poop" | 0:26 |

| Total length: | 19:14 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Nasal Retentive Calliope Music" | 2:03 |

| 2. | "Let's Make the Water Turn Black" | 2:01 |

| 3. | "The Idiot Bastard Son" | 3:18 |

| 4. | "Lonely Little Girl" (listed as "It's His Voice on the Radio" on the original LP sleeve) | 1:09 |

| 5. | "Take Your Clothes Off When You Dance" | 1:35 |

| 6. | "What's the Ugliest Part of Your Body? (Reprise)" | 0:57 |

| 7. | "Mother People" | 2:32 |

| 8. | "The Chrome Plated Megaphone of Destiny" | 6:25 |

| Total length: | 20:00 39:15 | |

Personnel

[edit]- The Mothers Today / The Mothers Yesterday[45]

- Frank Zappa – guitar, piano, lead vocals & editing

- Billy Mundi – drums, vocal, yak & black lace underwear

- Bunk Gardner – all woodwinds, mumbled weirdness

- Roy Estrada – electric bass, vocals, asthma

- Don Preston – retired

- Jimmy Carl Black – Indian of the group, drums, trumpet, vocals

- Ian Underwood – piano, woodwinds, wholesome

- Euclid James "Motorhead" Sherwood – road manager, soprano & baritone saxophone, all purpose weirdness & teen appeal (we need it desperately)

- Suzy Creamcheese (Pamela Zarubica) – telephone

- Dick Barber – snorks

- Also

- Gary Kellgren – creepy whispering

- Dick Kunc – cheerful interruptions

- Eric Clapton – has graciously consented to speak to you in several critical areas

- Spider – wants you to turn your radio around

- Uncredited

- Charlotte Martin – voice on "Are You Hung Up?"

- Vicki Kellgren – telephone

- Dave Aerni – guitars on "Nasal Retentive Calliope Music"

- Paul Buff – drums, bass, organ, saxes on "Nasal Retentive Calliope Music"

- Ronnie Williams – backwards voice on "Let's Make the Water Turn Black"

- Bob Stone – engineer on 1984 remix

- Arthur Barrow – bass on 1984 remix

- Chad Wackerman – drums on 1984 remix

- Production

- Frank Zappa – composer, arranger, producer

- Sid Sharp – conductor of orchestral segments

- Jerrold Schatzberg – photography

- Tiger Morse – fashions

- Cal Schenkel – plaster figures & all other artwork

- Tom Wilson – executive producer

- Nifty, Tough & Bitchen Youth Market Consultants for Bizarre Productions – packaging concept

- Gary Kellgren – engineer for two months of basic sessions at Mayfair Studios

- Dick Kunc – record & re-mix engineer for the final months of recording at Apostolic Studios

Charts

[edit]| Year | Chart | Position |

|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Billboard 200 | 30 |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "FZ Chronology 1965-69". Donlope. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ^ Rathbone, Oregano (October 10, 2020). "Hot Rats: Frank Zappa's Game-Changing Jazz-Rock Landmark". uDiscover Music. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ Reed, Ryan (July 4, 2020). "Top 25 American Classic Rock Bands of the '60s". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ "Frank Zappa". uDiscover Music. February 27, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Barry Miles (2004). Frank Zappa: The Biography (23. print. ed.). New York: Grove Press. pp. 160, 326. ISBN 0-8021-4215-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l David Fricke (2008). Lumpy Money (Media notes). Frank Zappa. Zappa Records.

- ^ a b c "FZ chronology: 1965-1969". www.donlope.net. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ a b "Frank Zappa Gig List: 1967". fzpomd.net. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "FZ Musicians & Collaborators H-L". www.donlope.net. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "The Secret Diva". procolharum.com. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Walley, David (1980). No Commercial Potential: The Saga of Frank Zappa. Da Capo Press. pp. 85, 89. ISBN 0-306-80710-6.

- ^ a b c Schinder, Scott; Schwartz, Andy (2008). Icons of Rock : An Encyclopedia of the Legends who Changed Music Forever. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-313-33847-2.

- ^ a b Courrier, Kevin (2002). Dangerous Kitchen: The Subversive World of Zappa. ECW Press. pp. 9, 81. ISBN 1-55022-447-6.

- ^ a b c d e Slaven, Neil (2003). Electric Don Quixote: The Definitive Story of Frank Zappa. Omnibus Press. pp. 85, 100, 105. ISBN 0-7119-9436-6.

- ^ a b "We're Only In It For The Money: Notes & Comments". www.donlope.net. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "We're Only In It For The Money Cover: Notes & Comments". www.donlope.net. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "1967". www.searchingforagem.com. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie (2009). White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-by-Day. Jawbone Press. p. 61. ISBN 9781906002220.

- ^ Epstein, Dan (January 30, 2018). "Velvet Underground's 'White Light/White Heat': 10 Things You Didn't Know". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ "Frank Zappa Gig List: 1965-1966". fzpomd.net. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ^ James, Billy (2002). Necessity is.... : the early years of Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention (2. ed.). Middlesex: SAF Publishing Ltd. p. 59. ISBN 0-946719-51-9.

- ^ a b c d e Huey, Steve. "We're Only in It for the Money – The Mothers of Invention / Frank Zappa". AllMusic. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Zappa, Frank with Occhiogrosso, Peter (1989). The Real Frank Zappa Book. New York: Poseidon Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-671-63870-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shuker, Roy (2001). Understanding popular music (2. ed.). Psychology Press. p. 121. ISBN 0-415-23509-X.

- ^ Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 42 – The Acid Test: Psychedelics and a sub-culture emerge in San Francisco. [Part 2]" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries. Track 1.

- ^ Ulrich, Charles (2018). The Big Note: A Guide to the Recordings of Frank Zappa. New Star Books. p. 605.

- ^ Penney, Stuart (May 1987). "Frank Zappa – The Early Albums". Record Collector. 93: 38–44.

- ^ "Zappa Patio". 2006. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ Kot, Greg (June 30, 1995). "Frankly Speaking". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ Sinclair, Tom (June 9, 1995). "We're Only in It for the Money". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- ^ Martin C. Strong (2024). The Great Rock Bible (1st ed.). Red Planet Books. ISBN 978-1-9127-3328-6.

- ^ Gary Graff, ed. (1996). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide (1st ed.). London: Visible Ink Press. ISBN 978-0-7876-1037-1.

- ^ "The Mothers of Invention: We're Only in It for the Money". Q (107): 150–151. August 1995.

- ^ Evans, Paul; Randall, Mac (2004). "Frank Zappa". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. pp. 902–904. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ Tom Hull. "Grade List: frank zappa". Tom Hull. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (December 26, 1995). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2007). Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0857125958.

- ^ Barret Hansen (April 6, 1968). "1968-04 We're Only in It for the Money (review)". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 12, 2011. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Pinnock, Tom (August 31, 2012). "Frank Zappa – Album By Album". Uncut. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ Colin Larkin (2006). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 136. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 12, 2005. Retrieved July 12, 2006.

- ^ "The Top 100: The Best Albums of the Last Twenty Years". Rolling Stone. No. 507. August 27, 1987. pp. 144–146.

- ^ Dimery, Robert (2009). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. Octopus Publishing Group, London. p. 156. ISBN 9781844036240. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ The National Recording Registry 2005, National Recording Preservation Board, The Library of Congress, May 24, 2005. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- ^ Mothers of Invention, The (2012). We're Only in It for the Money (fold-out insert). Zappa Records. ZR 3837.

- 1968 albums

- Albums produced by Frank Zappa

- Acid rock albums

- 1960s concept albums

- Frank Zappa albums

- The Mothers of Invention albums

- Self-censorship

- United States National Recording Registry recordings

- Verve Records albums

- Albums recorded at Capitol Studios

- United States National Recording Registry albums

- Collage album covers