Treaty of Bucharest (1913)

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (August 2011) |

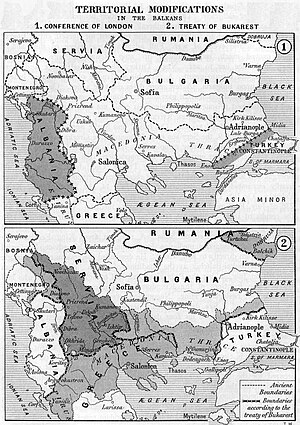

Borders of the Balkan states after the Treaty of Bucharest (below) | |

| Signed | 10 August 1913 |

|---|---|

| Location | Bucharest, Romania |

| Parties | |

The Treaty of Bucharest (Romanian: Tratatul de la București; Serbian: Букурештански мир; Bulgarian: Букурещки договор; Greek: Συνθήκη του Βουκουρεστίου) was concluded on 10 August 1913, by the delegates of Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia, Montenegro and Greece.[1] The Treaty was concluded in the aftermath of the Second Balkan War and amended the previous Treaty of London, which ended the First Balkan War. About one month later, the Bulgarians signed a separate border treaty (the Treaty of Constantinople) with the Ottomans, who had regained some territory west of the Enos-Midia Line during the second war.

Background

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2020) |

Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its gains in the First Balkan War, and especially with Greek and Serbian gains in Macedonia, launched an attack on its former allies in June 1913. The attacks were driven back, and the Greek and Serbian armies invaded Bulgarian-held territory in return. At the same time, the Ottomans advanced into Eastern Thrace and retook Adrianople, while Romania used the opportunity to invade Bulgaria from the north and advance against little opposition to within a short distance of the Bulgarian capital, Sofia. Isolated and surrounded by a more powerful coalition of opponents, Bulgaria was forced to agree to a truce and to peace negotiations to be held in the Romanian capital, Bucharest.

All important arrangements and concessions involving the rectification of the controverted international boundary lines were perfected in a series of committee meetings, incorporated in separate protocols, and formally ratified by subsequent action of the general assembly of delegates. Although the Ottomans had also participated in the Second Balkan War, they were not represented at this treaty. Instead, bilateral treaties were later concluded with Bulgaria (Treaty of Constantinople) and Greece (Treaty of Athens).

Gains in territory

[edit]Serbia

[edit]The eastern frontier of Serbia was drawn from the summit of Patarika, on the old frontier, and followed the watershed between the Vardar and the Struma rivers to the Greek-Bulgarian boundary, except that the upper valley of the Strumica remained in the possession of Bulgaria. The territory thus obtained by Serbia engulfed central Vardar Macedonia, including "Ochrida, Monastir, Kosovo, Istib, and Kotchana, and the eastern half of the Sanjak of Novi-Pazar".[2] These territories would today include Novi Pazar in Serbia, the disputed territory of Kosovo, and Ohrid, Štip, Kočani and Bitola in present-day North Macedonia. By this arrangement, Serbia increased its territory from 48,300 to 87,780 km2 (18,650 to 33,890 sq mi) and its population by more than 1.5 million.[1]

Greece

[edit]The boundary line separating Greece from Bulgaria was drawn from the crest of Belasica to the mouth of the Mesta (Nestos), on the Aegean Sea. This important territorial concession, which Bulgaria resolutely contested, in compliance with the instructions embraced in the notes which the Russian Empire and Austria-Hungary presented to the conference, increased the area of Greece from 64,790 to 108,610 km2 (25,020 to 41,930 sq mi) and its population from 2,660,000 to 4,363,000.[3]

The territory thus gained included large parts of Epirus and Macedonia, including Thessaloniki. The Greek-Bulgarian border was moved eastwards to beyond Kavala, thus restricting the Aegean seaboard of Bulgaria to an inconsiderable extent of 110 km, with only Dedeagach (modern Alexandroupoli) as a seaport. Within this region was also Florina.[4] In addition, Crete was definitively assigned to Greece and was formally taken over on 14 December that year.

Bulgaria

[edit]

Bulgaria's share of the spoils, although greatly reduced, was not entirely negligible. Its net gains in territory, which embraced a portion of Macedonia, Pirin Macedonia (or Bulgarian Macedonia), including the town of Strumica, Western Thrace, and 110 km of the Aegean littoral, were about 25,030 km2 (9,660 sq mi), and its population was increased by 129,490.[4]

In addition, Bulgaria agreed to dismantle all existing fortresses and bound itself not to construct forts at Rousse or Shumen or in any of the territory between these two cities, or within a radius of 20 kilometers around Balchik.[citation needed]

Romania

[edit]

Bulgaria ceded to Romania Southern Dobruja, lying north of a line extending from the Danube just above Tutrakan (Turtucaia) to the western shore of the Black Sea, south of Ekrene (Ecrene); Southern Dobruja has an approximate area of 6,960 km2 (2,690 sq mi), a population of 286,000, and includes the fortress of Silistra and the cities of Tutrakan on the Danube and Balchik (Balcic) on the Black Sea.[1]

Montenegro

[edit]The treaty awarded the regions of Berane, Ipek and Gjakova to Montenegro.[5]

Perception

[edit]According to Anderson and Hershey, the severe terms imposed on Bulgaria contrasted the ambitions of its government upon the entry into the Balkan War: the territory eventually gained was relatively circumscribed; Bulgaria had failed to gain Macedonia, which, with its large population of Bulgarians, was Sofia's avowed purpose in entering the war, and especially the districts of Ohrid and Bitola, which had been a main demand. With only a small outlet to the Aegean around the minor port of Dedeagach, the country had to abandon its project of Balkan hegemony.[4]

According to Anderson and Hershey, Greece, though a winner and triumphant after the acquisition of Thessaloniki and most of Macedonia up to and including the port of Kavala, still had outstanding issues.[4] Italy was opposed to Greek claims to Northern Epirus, and controlled the Greek-inhabited Dodecanese islands. In addition, the status quo of the islands of the Northeastern Aegean, which Greece had taken from the Ottomans, remained undetermined until February 1914, when the Great Powers recognized Greek sovereignty over them. Tensions with the Ottomans remained high, however, in the face of persecutions of Anatolian Greeks, leading to a crisis and a naval race in summer 1914 that was stopped only by the outbreak of World War I. At the end of the war, Greece still had claims to territories inhabited, at the time, by some 3 million Greeks.[citation needed]

Rise of Romania as a regional power

[edit]Following the Second Balkan War, in which Romania's intervention proved decisive, and the subsequent 1913 Treaty of Bucharest, Romania's dominant position in Southeastern Europe was confirmed. Romania also gained Southern Dobruja from Bulgaria.[6] Romania also raised the question of the Balkan Vlachs (that is, the Aromanians and Megleno-Romanians), whom it considered its compatriots. Too distant to be annexed, however, Romania took Southern Dobruja as compensation. Romania was the strongest nation in the Balkans, and thus it believed that it had to acquire territory, given that its neighbors were being aggrandized. Romania's argument that it had turned the scales of the war was accepted without serious objections, due in part to Bulgaria's attitude not attracting much compassion.[7] Despite not annexing the areas inhabited by Balkan Vlachs, Romania nevertheless obtained protection of the schools and churches of the Vlachs in the other Balkan states.[8] Thus, Romania was the only Balkan country to obtain guarantees from all three of its neighbors, which pledged to recognize its interest in, and respect the autonomy of the Balkan Vlachs.[9] The status of the Vlachs in Bulgarian territories was settled on 4 August, in Greek territories on 5 August and in Serbian territories between 5 and 7 August. The 1913 Treaty of Bucharest itself was signed on 10 August.[10] One notable aspect of this treaty was the lack of any real involvement from the European Great Powers. The Balkan states hurried to settle their differences before the Great Powers could again intervene in their affairs.[7] That's not to say, however, that the treaty went unnoticed, but the reactions among the Great Powers were mixed: there were rumblings from the capitals of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Russia, while the British and the French rejoiced in the "coming of age" of the Balkan states. The Great Powers did not revise the treaty.[9] Overall, the six Powers of the Concert of Europe had proved themselves to be rather helpless in Balkan crises. They had been unable to prevent the wars and subsequently could not ignore their results. The idea of revising the 1913 Treaty of Bucharest had to be abandoned.[11]

Subsequently, in 1914, Romania managed to impose its candidate for the throne of the Principality of Albania and support his reign by deploying military forces up to a battalion in strength.[12] Romania's brief stint as a significant power thus started with the 1913 Treaty of Bucharest, but ended in October 1916. Having joined the First World War on the side of the Allies on 27 August 1916, Romania launched an invasion of Transylvania. However, by 16 October, Transylvania had been cleared of Romanian troops.[13] One week later, on 23 October, Romania's chief seaport was captured by the Central Powers.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Anderson and Hershey, p. 439

- ^ Anderson, Frank Maloy; Hershey, Amos Shartle; National Board for Historical Service (1918). Handbook for the diplomatic history of Europe, Asia, and Africa, 1870–1914. Harvard University. Washington, D.C. : G.P.O. p. 439.

- ^ Anderson and Hershey, pp. 439–440

- ^ a b c d Anderson and Hershey, p. 440

- ^ State, United States Department of (1947). Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 741. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Richard C. Hall (2014). War in the Balkans: An Encyclopedic History from the Fall of the Ottoman Empire to the Breakup of Yugoslavia, ABC-CLIO. p. 241 [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b René Ristelhueber, Ardent Media, 1971, A History of the Balkan Peoples, p. 229 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Sam Stuart, Elsevier, May 12, 2014, Encyclopedia of Public International Law, p. 16 [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b Carole Fink, Cambridge University Press, 2006, Defending the Rights of Others: The Great Powers, the Jews, and International Minority Protection, 1878–1938, p. 64 [ISBN missing]

- ^ United States. Department of State, Oceana Publications, 1919, Catalogue of Treaties, 1814–1918, pp. 406–407

- ^ Sam Stuart, Elsevier, 2014, Encyclopedia of Public International Law, p. 17

- ^ Duncan Heaton-Armstrong, I.B. Tauris, 2005, The Six Month Kingdom: Albania 1914, pp. xii–xiii, xxviii, 30, 123–125, 136, 140 & 162.[ISBN missing]

- ^ "Canada in the Great World War: The turn of the tide". United publishers of Canada, limited. May 2, 1920. p. 395 – via Google Books.

- ^ David R. Woodward, Infobase Publishing, 2009, World War I Almanac, p. 151 [ISBN missing]

Sources

[edit]- Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. 1914. Retrieved 26 September 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- Anderson, Frank Maloy; Hershey, Amos Shartle (1918). "The Treaty of Bucharest, August 10, 1913". Handbook for the Diplomatic History of Europe, Asia, and Africa 1870–1914. Washington, DC: National Board for Historical Service, Government Printing Office. pp. 439–441.

- "Treaty of Peace Between Bulgaria and Roumania, Greece, Monte-Negro and Servia, Signed at Bukharest July 28/August 10, 1913; ratification exchanged August 30, 1913 (Translation)". The American Journal of International Law. VIII (1, Supplement, Official Documents): 13–27. January 1914. doi:10.2307/2212403. JSTOR 2212403.

- Miller, William (1923). "The Balkan League and its Results". The Ottoman Empire and its Successors, 1801–1922 (2nd ed.). Cambridge: At the University Press. p. 516. Retrieved 19 September 2018 – via Internet Archive.

Further reading

[edit]- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans: Twentieth Century. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521274593.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). . Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company.

- Austria-Hungary in World War I

- 20th century in Bucharest

- History of Greece (1909–1924)

- Macedonia under the Ottoman Empire

- Treaties of the Ottoman Empire

- 1913 in Bulgaria

- 1913 in Greece

- 1913 in Romania

- Vardar Macedonia (1912–1918)

- Treaties concluded in 1913

- Treaties involving territorial changes

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Romania

- Peace treaties of Romania

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Bulgaria

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Greece

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Serbia

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Montenegro

- Peace treaties of Bulgaria

- Second Balkan War

- Bulgaria–Romania relations

- Bulgaria–Greece relations

- Greece–Serbia relations

- Montenegro–Serbia relations

- Diplomatic conferences in Romania

- Peace treaties of Serbia

- Peace treaties of Greece

- Greece–Romania relations

- 1913 in Serbia

- August 1913 events

- 20th-century military history of Montenegro

- Territorial evolution of Romania

- Bulgaria–Serbia relations

- History of the Aromanians

- History of the Megleno-Romanians

- Military history of Bucharest