Mad Max (film)

| Mad Max | |

|---|---|

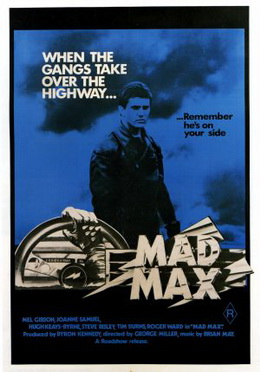

Original movie poster | |

| Directed by | George Miller |

| Written by | George Miller Byron Kennedy James McCausland |

| Produced by | Byron Kennedy Bill Miller |

| Starring | Mel Gibson Steve Bisley Joanne Samuel Hugh Keays-Byrne Tim Burns |

| Cinematography | David Eggby |

| Edited by | Cliff Hayes Tony Paterson |

| Music by | Brian May |

| Distributed by | - Australia - Village Roadshow Pictures - USA - American International Pictures - non-USA/Australia - Warner Bros. |

Release date | April 12 1979 |

Running time | 95 min |

| Country | Australia |

| Language | English |

| Budget | A$350,000 (estimated) |

Mad Max is a 1979 Australian apocalyptic action thriller film directed by George Miller and written by Miller and Byron Kennedy. The film, starring the then-little-known Mel Gibson, was released internationally in 1980.

This low-budget film's story of social breakdown, murder, and vengeance became the top-grossing Australian film, and has been credited for opening up the global market to Australian films. The movie was also notable for being the first Australian film to be shot with a widescreen anamorphic lens.

Mad Max was followed by two sequels, Mad Max 2 (aka The Road Warrior) and Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome. As of April, 2008, a third sequel, Mad Max 4: Fury Road, remains "in pre-production".

Plot summary

The story is set in Australia in the near future. It depicts a poorly-funded police unit called the Main Force Patrol (MFP), which struggles to protect the Outback's few remaining townspeople from violent motorcycle gangs. The film depicts future Australia as a bleak, dystopian and impoverished society that is facing a breakdown of civil order primarily due to widespread oil shortages. (This is not explained in this film but in the sequel, Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior.) The film introduces a young MFP police officer, Max Rockatansky badge number mfp4073 (Mel Gibson), who is considered the MFP's "top pursuit man".

A member of one of the biker gangs (nicknamed Nightrider) escapes from police custody by killing an officer and stealing his vehicle. Max pursues Nightrider in a high-speed chase, which results in Nightrider's death in a fiery car crash. After the dangerous chase (which results in injuries to a number of officers), the police chief warns Max that the bandits will be out for him now because of Nightrider's death.

The biker gang, which is led by Toecutter (Hugh Keays-Byrne), plans to avenge Nightrider's death by killing MFP officers. Meanwhile, they bully people and commit crimes such as one with a civilian couple that went escaping to the road after seeing the madness of the gang; the couple is overtaken, then both of them are raped and the car is wrecked. Then, Max and his close friend and fellow officer, Jim Goose (played by actor Steve Bisley) are informed about the incident and go to the crime's scenario. They find Toecutter's young protegé, Johnny the Boy (played by Tim Burns) and the girl of the couple in the middle of the wreckage. And by following the Patrol instructions, they take them to the Halls of Justice.

They are notified for a visit from the Court. Instead of a trial, the judge decides to set Johnny free because no witnesses show up. Since there are no allegations to charge him, they declare no contest for that case. After hearing that, Goose is shocked because of the decision, and starts a complaint that ends in desires of revenge inside both Goose and Johnny.

Some time later Johnny the Boy sets a trap for Goose while he was attending a show into the Sugartown Cabaret. When Goose's vehicle is flipped over, the bikers burn him alive. Goose survives, but after seeing his charred body in the hospital's burn ward, Max becomes angry and disillusioned with the police force and resigns from the MFP with no intention of returning. He takes a road trip with his wife and infant son in the relatively peaceful coastal area North of their home.

While on vacation, Max's wife, Jessie, (played by Joanne Samuel) runs into Toecutter's gang, who attempt to molest her. She escapes, but the gang manage to track her to the home where she and Max are staying. While attempting to escape from the gang again, Jessie and her son are run down by the gang who leave their crushed bodies in the middle of the road. Max arrives too late to intervene. His son is pronounced dead on the scene, while his wife suffers massive injuries. (It is revealed in Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior that she later died from her injuries.)

Filled with obsessive rage, Max once again dons his police outfit and straps on his sawn-off shotgun. Driving the supercharged, black Pursuit Special, he drives out to avenge the death of his family. He hunts down and kills the gang members one by one, including the Toecutter. When Max finds Johnny the Boy, he handcuffs Johnny's ankle to a wrecked, overturned vehicle with a ruptured gas tank. Max lights a crude time-delay fuse and gives Johnny a hacksaw, leaving him the choice of sawing through either the handcuffs (10 minutes) or his ankle (five minutes), and then drives off into the desolate outback. A few moments later, the gas tank explodes.

Conception

George Miller was a medical doctor in Australia, working in a hospital emergency room, where he saw many injuries and deaths of the types depicted in the movie. While in residency at a Melbourne hospital, he met amateur film maker Byron Kennedy at a summer film school in 1971. The duo produced the short film Violence in the Cinema, Part 1, which was screened at a number of film festivals and won several awards. Eight years later, the duo created Mad Max, with the assistance of first time screenwriter James McCausland (who appears in the film as the bearded man in an apron in front of the diner).

Miller believed that audiences would find his violent story to be more believable if set in a bleak, dystopic future. The film was shot over a period of twelve weeks in Australia, between December 1978 and February 1979, just outside Melbourne. Many of the car-chase scenes for the original Mad Max were filmed near the town of Lara, just north of Geelong (Victoria, Australia). The movie was shot with a widescreen anamorphic lens, the first Australian film to use one.

Mel Gibson, a complete unknown at this point, went to auditions with his friend and classmate Bisley (who would later land the part of Jim Goose). Gibson went to auditions in poor shape, as the night before he had gotten into a drunken brawl with three men at a party, resulting in a swollen nose, a broken jawline, and various other bruises. Mel showed up at the audition the next day looking like a "black and blue pumpkin" (his own words). Mel did not expect to get the role and only went to accompany his friend. However, the casting agent liked the look and told Mel to come back in two weeks, telling him "we need freaks." When Gibson returned, he was not recognized because his wounds had healed almost completely; he received the part anyway.[1]

Due to the film's low budget, only Mel Gibson was given a jacket and pants made from real leather. All the other actors playing police officers wore vinyl outfits. The police cars were repeatedly repainted to give the illusion that more cars were used; often they were driven with the paint still wet. The film's post-production was done in Kennedy's house, with Wilson and Byron editing the film in Byron's bedroom on a home-built editing machine that Byron's father, an engineer, had designed for them. The duo also edited the sound in Kennedy's house.

Reception

The film initially received a mixed reaction from critics. Tom Buckley of the New York Times called it "ugly and incoherent" [2], though Variety magazine praised the directorial debut by Miller.[3]

Though the film had a limited run in the United States and earned only $8 million there, it did very well elsewhere around the world and went on to earn $100 million worldwide.[4] Since it was independently financed with a reported budget of just $300,000 AUD, it was a major financial success. For twenty years, the movie held a record in Guinness Book of Records as the highest profit-to-cost ratio of a motion picture, conceding the record only in 2000 to The Blair Witch Project. The film was awarded three Australian Film Institute Awards in 1979 (for editing, sound, and musical score).[5]

Releases

When the film was first released in America, all the voices, including that of Mel Gibson's character, were dubbed by U.S. performers at the behest of the distributor, American International Pictures, for fear that audiences would not take warmly to actors speaking entirely with Australian accents. Much of the Australian slang and terminology was also replaced with American usages (examples: "See looks!" became "Look see!", "windscreen" became "windshield", "very toey" became "super hot", and "probie" became "rookie"). AIP also altered the operator's duty call on Jim Goose's bike in the beginning of the movie (it ended with "Come on, Goose, where are you?"). The only dubbing exceptions were the voice of the singer in the Sugartown Cabaret (played by Robina Chaffey), the voice of Charlie (played by John Ley) through the mechanical voice box, and Officer Jim Goose (played by Steve Bisley), singing as he drives a truck before being ambushed.

The original Australian dialogue track was finally released in the U.S. in 2000 in a limited theatrical reissue by MGM, the film's current rights holders (it has since been released in the U.S. on DVD with both the US and Australian soundtracks on separate tracks). Both New Zealand and Sweden initially banned the film.

Two sequels followed, Mad Max 2 (known in North America as The Road Warrior), and Mad Max 3 (known in North America as Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome) while a fourth movie, Mad Max 4: Fury Road, is in pre-production.

Vehicles

Max's yellow Interceptor was a 1974 Ford Falcon XB sedan (previously, a Melbourne police car) with a 351ci Cleveland V8 engine and many other modifications. The Big Bopper, driven by Roop and Charlie, was also a 1974 Ford Falcon XB sedan, but was powered by a 302ci Cleveland V8. The March Hare, driven by Sarse and Scuttle, was an in-line-six-powered 1972 Ford Falcon XA sedan (this car was formerly a Melbourne taxi cab).

The most memorable car, Max's black Pursuit Special was a limited GT351 version of a 1973 Ford XB Falcon Coupe (sold in Australia from December 1973 to August 1976) which was modified by the film's art director Jon Dowding. After filming was over, this Interceptor was bought and restored by Bob Forsenko, and is currently on display in the Cars of the Stars Motor Museum in Cumbria, England [6].

The Nightrider's vehicle, another Pursuit Special, was a 1972 Holden HQ LS Monaro coupe.

The car driven by the civilian couple that is destroyed by the bikers is a 1959 Chevrolet Impala sedan.

Of the motorcycles that appear in the film, 14 were donated by Kawasaki and were driven by a local Victorian motorcycle gang, the Vigilantes, who appeared as members of Toecutter's gang. By the end of filming, fourteen vehicles had been destroyed in the chase and crash scenes, including the director's personal Mazda Bongo (the small, blue van that spins uncontrollably after being struck by the Big Bopper in the film's opening chase).

See also

- Pursuit Special – Max’s black car.

References

- ^ Mary Packard and the editors of Ripley Entertainment, ed. (2001). Ripley's Believe It or Not! Special Edition. Leanne Franson (illustrations) (1st ed. ed.). Scholastic Inc. ISBN 0-439-26040-X.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=EE05E7DF173BBB2CA7494CC6B6799C836896

- ^ http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117792854.html?categoryid=31&cs=1&p=0

- ^ http://www.the-numbers.com/movies/1980/0MMX1.php

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0079501/awards

- ^ Cars of the Stars Motor Museum

- Mick Broderick, "Heroic Apocalypse: Mad Max, Mythology, and the Millennium", in Christopher Sharrett, ed., Crisis Cinema: The Apocalyptic Idea in Postmodern Narrative Film.

- Delia Falconer, "'We Don't Need to Know the Way Home': The Disappearance of the Road in the Mad Max Trilogy," in Steven Cohen and Abe Vigoda, eds., The Road Movie Book.

- Peter C. Hall and Richard Erlich. "Beyond Topeka and Thunderdome: Variations on the Comic-Romance Pattern in Recent SF Film," Science-Fiction Studies, 14 (November 1987).

- Adrian Martin. The Mad Max Movies, Sydney and Canberra: Currency Press and Screenbound Australia, 2003.

- Meaghan Morris. "White Panic or Mad Max and the Sublime," Kuan-Hsing Chen, ed., Trajectories: Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. London and NewYork: Routledge, 1998.

- Jerome F. Shapiro, Atomic Bomb Cinema: The Apocalyptic Imagination on Film, New York: Routledge, 2002.

- To the Max - Behind the Scenes of a Cult Classic, Mad Max DVD (Village Roadshow).

External links

- Mad Max Online – Home to the original Mad Max movie, maintained by members of the cast and crew.

- Mad Max Replica Stats – Displays a comprehensive list of all known Mad Max Replicas in the world.

- Articles needing cleanup from July 2008

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from July 2008

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from July 2008

- 1979 films

- American International Pictures films

- Films that portray the future

- Films set in Australia

- Mad Max films

- Directorial debut films

- Australian films

- Post-apocalyptic science fiction films