Bulgaria

Republic of Bulgaria Република България | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Съединението прави силата (Bulgarian) "Saedinenieto pravi silata" (transliteration) "Unity makes strength"1 | |

| Anthem: Мила Родино (Bulgarian) [Mila Rodino] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (transliteration) Dear Motherland | |

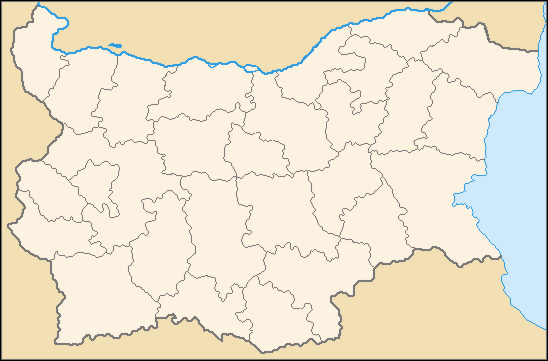

Location of Bulgaria (dark green) within Europe and the EU | |

| Capital and largest city | Sofia |

| Official languages | Bulgarian |

| Ethnic groups | 84% Bulgarians, 9% Turkish, 5% Roma, 2% other groups[1] |

| Demonym(s) | Bulgarian |

| Government | Parliamentary republic |

| Georgi Parvanov | |

| Sergei Stanishev | |

| Georgi Pirinski | |

| Formation | |

• Medieval kingdom | 681[2] |

• Last previously independent state2 | 1422 |

• Re-establishment (under nominal Ottoman suzerainty) | 1878 |

• Unification with Eastern Rumelia | 1885 |

• Full sovereignty | 1908 |

| Area | |

• Total | 110,910 km2 (42,820 sq mi) (104th) |

• Water (%) | 0.3 |

| Population | |

• 2009 estimate | |

• 2001 census | |

• Density | 68.9/km2 (178.5/sq mi) (124th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2008 estimate |

• Total | $93.8 billion[3] (63rd) |

• Per capita | $12,370[3] (65th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2008 estimate |

• Total | $52.0 billion[3] (75th) |

• Per capita | $6,850[3] (88th) |

| Gini (2003) | 29.2 low inequality |

| HDI (2006) | Error: Invalid HDI value (56th) |

| Currency | Lev3 (BGN) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | 359 |

| ISO 3166 code | BG |

| Internet TLD | .bg4 |

| |

The state of Bulgaria (Template:Lang-bg, transliterated: [Balgariya] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help),[4] pronounced IPA: [bəlˈgarija]), international transliteration Bălgarija, officially the Republic of Bulgaria (Република България, [Republika Balgariya] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), pronounced IPA: [rɛˈpubliˌka bəlˈgarija]) has played a significant role in the Balkans in south-eastern Europe for over fourteen centuries. It borders five other countries: Romania to the north (mostly along the River Danube), Serbia and the Republic of Macedonia to the west, and Greece and Turkey to the south. The Black Sea defines the extent of the country to the east.

Bulgaria includes parts of the Roman provinces of Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia. Old European culture within the territory of present-day[update] Bulgaria started to produce golden artifacts by the fifth millennium BC.[5]

The first Bulgarian kingdoms on European soil date back to the early Middle Ages (VIIth century). All Bulgarian political entities that subsequently emerged preserved the traditions (in ethnic name, language and alphabet) of the First Bulgarian Empire (632/681– 1018), which at times covered most of the Balkans and spread its alphabet, literature and culture among the Slavic and other peoples of Eastern Europe. Centuries later, with the decline of the Second Bulgarian Empire (1185– 1396/1422), Bulgarian kingdoms came under Ottoman rule for nearly five centuries. The Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878 led to the re-establishment of a Bulgarian state as a constitutional monarchy in 1878, with the Treaty of San Stefano marking the birth of the Third Bulgarian State. In 1908 while social strife was brewing at the core of the Ottoman Empire, the Alexander Malinov government and Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria formally proclaimed the full sovereignty of the state at the ancient capital of Veliko Turnovo.[6] After World War II, in 1945 Bulgaria became a communist state and part of the Eastern Bloc. Todor Zhivkov dominated Bulgaria politically for 33 years (from 1956 to 1989). In 1990, after the Revolutions of 1989, the Communist party gave up its monopoly on power and Bulgaria transitioned to democracy and free-market capitalism.

Currently[update] Bulgaria functions as a parliamentary democracy under a unitary constitutional republic. A member of the European Union since 2007 and of NATO since 2004, it has a population of approximately 7.6 million. Bulgaria has a high HDI.[citation needed]

Geography

Geographically and in terms of climate, Bulgaria features notable diversity with the landscape ranging from the Alpine snow-capped peaks in Rila, Pirin and the Balkan Mountains to the mild and sunny Black Sea coast; from the typically continental Danubian Plain (ancient Moesia) in the north to the strong Mediterranean climatic influence in the valleys of Macedonia and in the lowlands in the southernmost parts of Thrace.

Phytogeographically, Bulgaria straddles the Illyrian and Euxinian provinces of the Circumboreal region within the Boreal kingdom. According to the WWF and to the European Environment Agency's Digital Map of European Ecological Regions, the territory of Bulgaria subdivides into two main ecoregions: the Balkan mixed forests and Rhodope montane mixed forests. Small parts of four other ecoregions also occur on Bulgarian territory.

Relief

The Balkan Peninsula derives its name from the Balkan or Stara Planina mountain-range, which runs through the centre of Bulgaria and extends into eastern Serbia.

Bulgaria comprises portions of the regions known in classical times as Moesia, Thrace, and Macedonia. The mountainous southwest of the country has two alpine ranges — Rila and Pirin — and further east stand the lower but more extensive Rhodope Mountains. The Rila range includes the highest peak of the Balkan Peninsula, Musala, at 2,925 meters (9,596 ft); the long range of the Balkan mountains runs west-east through the middle of the country, north of the famous Rose Valley. Hilly country and plains lie to the southeast, along the Black Sea coast in the east, and along Bulgaria's main river, the Danube in the north.

Mineral resources

The country possesses relatively rich mineral-resources, including vast reserves of lignite and anthracite coal; non-ferrous ores such as copper, lead, zinc and gold. It has large deposits of manganese ore in the north-east. Smaller deposits exist of iron, silver, chromite, nickel and others. Bulgaria has abundant non-metalliferous minerals such as rock-salt, gypsum, kaolin and marble.

Hydrography

Bulgaria has a dense network of about 540 rivers, but with the notable exception of the Danube, most have short lengths and low water-levels.[7]

Most rivers flow through mountainous areas; fewer in the Danubian Plain, Upper Thracian Plain and especially Dobrudzha. Two catchment basins exist: the Black Sea (57% of the territory and 42% of the rivers) and the Aegean Sea (43% of the territory and 58% of the rivers) basins. The longest river located solely in Bulgarian territory, the Iskar, has a length of 368 km. Other major rivers include the Struma and the Maritsa River in the south.

Rila and Pirin feature around 260 glacial lakes; the country also has several large lakes on the Black Sea coast and more than 2,200 dam lakes. Many mineral springs exist, located mainly in the south-western and central parts of the country along the faults between the mountains.

The Bulgarian word for spa, баня, transliterated as banya, appears in some of the names of more than 50 spa towns and resorts including Sapareva Banya, Hisarya, Sandanski, Bankya, Varshets, Pavel Banya, Devin, Velingrad and many others.

Climate

Bulgaria has a temperate climate, with cold winters (with considerable snowfall) and hot summers (rainy at first and dry during the second half). The Black Sea coast has a milder climate than rest of the country, but strong winds and violent local storms occur frequently during the winter. The barrier effect of the Balkan Mountains has some influence on climate throughout the country: northern Bulgaria gets colder and receives more rain than the southern regions. The Northern Thracian Plain (middle-south Bulgaria) has a climate resembling that of the Corn Belt in the United States. Precipitation in Bulgaria averages about 630 millimetres per year. Drier areas include Dobrudja and the northern coastal strip, while the higher parts of the Rila, Pirin and Stara Planina (Balkan) Mountains receive the highest levels of precipitation. In summer, temperatures in the southest Bulgaria often exceed 40 degrees Celsius, but remain cooler by the coast. The town of Sadovo, near Plovdiv, has recorded the highest known temperature: 45.2 degrees Celsius. The recorded absolute minimum temperature of -39.3 degrees celsius occurred west of Sofia, near the town of Trun. The usual temperature around the Stara Planina region averages 10 to 15 degrees celsius.

The highest Bulgarian mountains (over 900 or 1000 meters above sea-level) have an alpine climate. The lowest parts of the Struma and Maritza valleys have a subtropical (Mediterranean) influences, as do the Eastern Rhodope or Low Rhodope mountains.

Urban geography

Bulgaria's larger cities include:[8]

| Place | City | Population | Place | City | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. |

Sofia | 1,393,565 | 6. |

Stara Zagora | 152,619 |

| 2. |

Plovdiv | 379,119 | 7. |

Pleven | 122,989 |

| 3. File:Varna-coat-of-arms.svg | Varna | 352 211 | 8. File:Sliven Bulgaria coat of arms.png | Sliven | 104,304 |

| 4. |

Burgas | 203,797 | 9. |

Dobrich | 103,309 |

| 5. |

Rousse | 167,715 | 10. |

Shumen | 89,613 |

Bulgaria operates a scientific station, the St. Kliment Ohridski Base, on Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands off the coast of Antarctica.

History

Prehistory and Antiquity

Prehistoric cultures in the Bulgarian lands include the Neolithic Hamangia culture and Vinča culture (6th to 3rd millennia BC), the eneolithic Varna culture (5th millennium BC; see also Varna Necropolis), and the Bronze Age Ezero culture. The Karanovo chronology serves as a gauge for the prehistory of the wider Balkans region.

The Thracians, the earliest known identifiable people to inhabit the present-day territory of Bulgaria, have left traceable marks among all the Balkan region despite its tumultuous history of many conquests. Cultural historians[who?] rank the Panagyuriste treasure as one of the most splendid achievements of the Thracian culture.

The Thracians lived divided into numerous separate tribes until King Teres united most of them around 500 BC in the Odrysian kingdom, which peaked under the kings Sitalces and Cotys I (383-359 BC). In 188 BC the Romans invaded Thrace, and warfare continued until 45 AD when Rome finally conquered the region. The conquerors quickly Romanised the population. By the time the Slavs arrived, the Thracians had already lost their indigenous identity and had dwindled in number following frequent invasions.

The Slavs and Old Great Bulgaria

The Slavs emerged from their original homeland (location not definitively established: see Slavic peoples) in the early 6th century and spread to most of the eastern Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the Balkans, forming in the process three main branches: the West Slavs, the East Slavs and the South Slavs. Some eastern South Slavs became ancestors of the modern Bulgarians. They assimilated what remained of the Thracians.[9] Modern Bulgarians derive much of their culture, language and self-determination from these early immigrants.

In 632, the Bulgars, an ancient nation that formed numerous kingdoms[10][11][12] throughout Eurasia and stemmed from a largely enigmatic socio-cultural lineage (theorised as of either Indo-European[10][11][12] [verification needed] or Turkic descent), originally from Central Asia,[10][11][12] formed under the leadership of Khan Kubrat an independent state called Great Bulgaria, situated between the lower course of the Danube to the west, the Black Sea and the Azov Sea to the south, the Kuban River to the east, and the Donets River to the north.[13]

Pressure from the Khazars led to the subjugation of Great Bulgaria in the second half of the 7th century. Some of the Bulgars from that territory later migrated to the northeast to form a new state called Volga Bulgaria (around the confluence of the Volga and Kama Rivers), which lasted until the 13th century.

First Bulgarian Empire

Kubrat’s successor, Khan Asparuh, migrated with some of the Bulgar tribes to the lower courses of the rivers Danube, Dniester and Dniepr (known as Ongal), and conquered Moesia and Scythia Minor (Dobrudzha) from the Byzantine Empire, expanding his new khanate further into the Balkan Peninsula.[15] A peace treaty with Byzantium in 681 and the establishment of the Bulgar capital of Pliska south of the Danube mark the beginning of the First Bulgarian Empire. At the same time one of Asparuh's brothers, Kuber, settled with another Bulgar group in present-day[update] Macedonia.[citation needed]

During the siege of Constantinople in 717-718 the Bulgars honoured their treaty with the Byzantines by sending troops to help the populace of the imperial city. According to the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes, in the decisive battle the Bulgarians killed 22,000 Arabs.[16] Contemporaries across the continent called the Bulgarian Emperor Tervel the "Saviour of Europe".[citation needed]

The influence and territorial expansion of Bulgaria increased further during the rule of Khan Krum,[17] who in 811 won a decisive victory against the Byzantine army led by Nicephorus I in the Battle of Pliska.[18]

In 864, Bulgaria accepted Eastern Orthodox Christianity.[19]

Bulgaria became a major European power in the ninth and the tenth centuries, while fighting with the Byzantine Empire for the control of the Balkans. This happened under the rule (852–889) of Boris I. During his reign, the Cyrillic alphabet originated in Preslav and Ohrid,[20] adapted from the Glagolitic alphabet invented by the monks Saints Cyril and Methodius.[21]

The Cyrillic alphabet became the basis for further cultural development. Centuries later, this alphabet, along with the Old Bulgarian language, fostered the intellectual written language (lingua franca) for Eastern Europe, known as Church Slavonic. The greatest territorial extension of the Bulgarian Empire — covering most of the Balkans — occurred under Simeon I, the first Bulgarian Tsar (Emperor), son of Boris I.[22]

However, Simeon's greatest achievement consisted of Bulgaria developing a rich, unique Christian Slavonic culture, which became an example for the other Slavonic peoples in Eastern Europe and ensured the continued existence of the Bulgarian nation regardless of the centrifugal forces that threatened to tear it into pieces throughout its long and war-ridden history.

Following a decline in the mid-tenth century (worn out by wars with Croatia, by frequent Serbian rebellions sponsored by Byzantine gold, and by disastrous Magyar and Pecheneg invasions),[23] Bulgaria collapsed in the face of an assault of the Rus' in 969-971.[24]

The Byzantines then began campaigns to conquer Bulgaria. In 971, they seized the capital Preslav and captured Emperor Boris II.[25] Resistance continued under Tsar Samuil in the western Bulgarian lands for nearly half a century. The country managed to recover and defeated the Byzantines in several major battles taking the control of the most of the Balkans and in 991 invaded the Serbian state.[26] However, the Byzantines led by Basil II (Basil the Bulgar-Slayer) destroyed the Bulgarian state in 1018 after their victory at Kleidion.[27]

Byzantine Bulgaria

In the first decade after the establishment of Byzantine rule, no evidence remains of any major attempt at resistance or any uprising of the Bulgarian population or nobility. Given the existence of such irreconcilable opponents to Byzantium as Krakra, Nikulitsa, Dragash and others, such apparent passivity seems difficult to explain. Some historians[28] explain this fact by concessions that Basil II granted the Bulgarian nobility in order to gain their obedience. In the first place, Basil II guaranteed the indivisibility of Bulgaria in its former geographic borders and did not abolish officially the local rule of the Bulgarian nobility that now became part of Byzantine aristocracy as archons or strategoi. Second, special charters (royal decrees) of Basil II recognised the autocephaly of the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid and set up its boundaries, securing the continuation of the dioceses already existing under Samuel, their property and other privileges.[29]

The people of Bulgaria challenged Byzantine rule several times in the 11th and then again later in the early 12th century. The biggest uprising occurred under the leadership of Peter II Delyan, (proclaimed Emperor of Bulgaria in Belgrade in 1040). In the mid to late 11th century, the Normans, fresh from their recent conquests in southern Italy and Sicily, landed in the Balkans and began advancing against the Byzantine Empire. It took the Byzantines until 1185 before the Normans were driven out but until then they posed a constant threat to Byzantine Bulgaria. In 1091 another invasion came in the form of the Pechenegs. However, these too were crushed at Levounion and again in c. 1120 by the Byzantine Empire. After that, the Hungarians made an attempt to increase their influence beyond the Danube river; John Comnenus' campaigns along the Danube eventually drove back the Hungarians as well by c.1140. It would be another 45 years before Bulgaria would attain independence. Until that time, Bulgarian nobles ruled the province in the name of the Byzantine Empire until a rebellion by Ivan Asen I and Peter IV of Bulgaria led to the establishment of the Second Bulgarian Empire.

Second Bulgarian Empire

From 1185, the Second Bulgarian Empire once again established Bulgaria as an important power in the Balkans for two more centuries with its capital based in Veliko Turnovo and under the Asen dynasty. Kaloyan, the third of the Asen monarchs, extended his dominions to Belgrade, Nish and Skopie (Uskub); he acknowledged the spiritual supremacy of the pope, and received the royal crown from a papal legate.[9] The Bulgarian ruler from 1218 to 1241, Ivan Asen II extended his rule over Albania, Epirus, Macedonia and Thrace.[30] During his reign the state saw a period of cultural growth, with important artistic achievements of the Tarnovo artistic school.[9] The dynasty of the Asens became extinct in 1257, and as a result of the Tatar invasions (beginning in the later 13th century), of internal conflicts and of the constant attacks from the Byzantines and the Hungarians, the power of the country declined until the end of the 13th century. From 1300, under Emperor Theodore Svetoslav Bulgaria regained its strength, but by the end of the fourteenth century the country had disintegrated into several feudal principalities, which the Ottoman Empire eventually conquered.

Ottoman rule

By the end of the 14th century factional divisions between Bulgarian feudal landlords (boyars) had gravely weakened the cohesion of the Second Bulgarian Empire. It split into three small Tsardoms and several semi-independent principalities which fought among themselves, and also with Byzantines, Hungarians, Serbs, Venetians, and Genoese. In these battles they often allied with the Ottoman Turks. Similar situations of internecine quarrel and infighting existed also in Byzantium and Serbia. In the period 1365-1370 the Ottomans conquered most of the Bulgarian towns and fortresses south of the Balkan Mountains.[31]

In 1393 the Ottoman Turks captured Tarnovo, the capital of the Second Bulgarian Empire, after a three-month siege. With the fall of the Vidin Tsardom following the defeat of a Christian crusade at the Battle of Nicopolis in 1396, the Ottomans finally subjugated and occupied Bulgaria.[32][33][34] When a Polish-Hungarian crusade under the command of Władysław III of Poland set out to free the Balkans in 1444, the Turks defeated it in the battle of Varna.

Some accounts of the five centuries of Ottoman rule highlight its violence and oppression. The Ottomans decimated the Bulgarian population, which lost most of its cultural relics. Turkish authorities destroyed most of the medieval Bulgarian fortresses in order to prevent rebellions. Large towns and the areas where Ottoman power predominated remained severely depopulated until the nineteenth century.[14]

The new authorities dismantled Bulgarian institutions at anything above the village or communal level, and merged the separate Bulgarian Church into the Orthodox Patriarchate in Constantinople (Istanbul) (although a small, semi-independent Bulgarian Church did survive until 1767).

Bulgarians in the Ottoman empire had to endure a number of disabilities; they paid more taxes than Moslems, they lacked legal equality with Moslems, they could not carry arms, their clothes could not rival those of Moslems in color, nor could their churches tower as high as mosques.[35] Those who did convert, the Pomaks, retained Bulgarian language, dress and some customs compatible with Islam.[33][34]

The Ottoman system started to decline by the 17th century, and at the end of the 18th had all but collapsed. Central government weakened over the decades, and this had allowed a number of local Ottoman holders of large estates to establish personal ascendancy over separate regions.[36] During the last two decades of the 18th and first decades of the 19th centuries the Balkan Peninsula dissolved into virtual anarchy, a period known in Bulgarian as the kurdjaliistvo after the armed bands of Turks or kurdjalii who plagued the area at this time. In many regions thousands of peasants fled from the countryside either to local towns or (more probably) to the hills or forests; some even fled beyond the Danube to Moldova, Wallachia or southern Russia.[33][37]

In the 18th and especially during the 19th century, conditions improved in certain areas. Some towns — such as Gabrovo, Tryavna, Karlovo, Koprivshtitsa, Lovech, Skopie — prospered. The Bulgarian peasants actually possessed their land, although it officially belonged to the sultan. The 19th century also brought improved communications, transportation and trade. The first factory in the Bulgarian lands opened in Sliven in 1834, and the first railway system started running (between Rousse and Varna) in 1865.

Throughout the five Ottoman centuries Bulgarian people organized many attempts to re-establish their own state. The National awakening of Bulgaria became one of the key factors in the struggle for liberation. In the 19th century there came into existence the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee and the Internal Revolutionary Organisation led by liberal revolutionaries such as Vasil Levski, Hristo Botev, Lyuben Karavelov and many others.

In 1876, the April uprising broke out: the largest and best-organized Bulgarian rebellion against the Ottoman Empire. Though crushed by the Ottoman authorities, the uprising (together with the 1875 rebellion in Bosnia) prompted the Great Powers to convene the 1876 Conference of Constantinople, which delimited the ethnic Bulgarian territories as of the late 19th century, and elaborated the legal and political arrangements for establishing two autonomous Bulgarian provinces. The Ottoman Government declined to comply with the Great Powers’ decisions, making it possible for Russia to seek a solution by force without risking military confrontation with other Great Powers as in the Crimean War of 1854 to 1856..

The Kingdom of Bulgaria

Following the Russo-Turkish War, 1877-1878 (when Russian soldiers together with a Romanian expeditionary force and volunteer Bulgarian troops defeated the Ottoman armies), the Treaty of San Stefano (3 March 1878), set up an autonomous Bulgarian principality. The Western Great Powers immediately rejected the treaty: they became aware that a large Slavic country in the Balkans might serve Russian interests. This led to the Treaty of Berlin (1878) which provided for an autonomous Bulgarian principality comprising Moesia and the region of Sofia. Alexander, Prince of Battenberg, took up the position of Bulgaria's first Prince. Most of Thrace became part of the autonomous region of Eastern Rumelia, whereas the rest of Thrace and all of Macedonia returned to the sovereignty of the Ottomans. After the Serbo-Bulgarian War and unification with Eastern Rumelia in 1885, the Bulgarian principality proclaimed itself a fully independent kingdom on 5 October (22 September O.S.), 1908, during the reign of Ferdinand I of Bulgaria.

Ferdinand, a prince from the ducal family of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, became the Bulgarian Prince after Alexander von Battenberg abdicated in 1886 following a coup d'état staged by pro-Russian army-officers. (Although the counter-coup coordinated by Stefan Stambolov succeeded, Prince Alexander decided not to remain the Bulgarian ruler without the approval of Alexander III of Russia.) The struggle for liberation of the Bulgarians in the Adrianople Vilayet and in Macedonia continued throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, culminating with the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising organised by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization in 1903.

The Balkan Wars and World War I

In 1912 and 1913, Bulgaria became involved in the Balkan Wars, first entering into conflict alongside Greece, Serbia and Montenegro against the Ottoman Empire. The First Balkan War (1912-1913) proved a success for the Bulgarian army, but a conflict over the division of Macedonia arose amongst the victorious allies. The Second Balkan War (1913) pitted Bulgaria against Greece and Serbia, joined by Romania and Turkey. After its defeat in the Second Balkan War, Bulgaria lost considerable territory conquered in the first war, as well as Southern Dobrudzha and parts of the region of Macedonia.

During World War I, Bulgaria found itself fighting again on the losing side as a result of its alliance with the Central Powers. Defeat in 1918 led to new territorial losses (the Western Outlands to Serbia, Western Thrace to Greece and the re-conquered Southern Dobrudzha to Romania). The Balkan Wars and World War I led to the influx of over 250,000 Bulgarian refugees from Macedonia, Eastern and Western Thrace and Southern Dobrudzha.

The interwar years

In September 1918, Tsar Ferdinand abdicated in favour of his son Boris III in order to head off revolutionary tendencies. Under the Treaty of Neuilly (November 1919), Bulgaria ceded its Aegean coastline to Greece, recognized the existence of Yugoslavia, ceded nearly all of its Macedonian territory to that new state, and had to give Dobrudzha back to the Romanians. The country had to reduce its army to 20,000 men, and to pay reparations exceeding $400 million. Bulgarians generally refer to the results of the treaty as the "Second National Catastrophe".

Elections in March 1920 gave the Agrarians a large majority, and Aleksandar Stamboliyski formed Bulgaria's first peasant government. He faced huge social problems, but succeeded in carrying out many reforms, although opposition from the middle and upper classes, the landlords and the officers of the army remained powerful. In March 1923 Stamboliyski signed an agreement with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia recognising the new border and agreeing to suppress Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (VMRO), which favoured a war to regain Macedonia from Bulgaria. This triggered a nationalist reaction, and the Bulgarian coup d'état of 9 June 1923 eventually resulted in Stamboliykski's assassination. A right-wing government under Aleksandar Tsankov took power, backed by the army and the VMRO, which waged a White terror against the Agrarians and the Communists. In 1926 the Tsar persuaded Tsankov to resign, a more moderate government under Andrey Lyapchev took office and an amnesty was proclaimed, although the Communists remained banned. A popular alliance including the re-organised Agrarians won elections in 1931 under the name Popular Bloc.

In May 1934 another coup took place, removing the Popular Bloc from power and establishing an authoritarian military régime headed by Kimon Georgiev. A year later Tsar Boris managed to remove the military régime from power, restoring a form of parliamentary rule (without the re-establishment of the political parties) and under his own strict control. The Tsar's regime proclaimed neutrality, but gradually Bulgaria gravitated into alliance with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.

World War II

After occuping Southern Dobrudzha in 1940, Bulgaria became allied with the Axis Powers, although it never declared war on the USSR and declined to participate in Operation Barbarossa. During World War II Nazi Germany allowed Bulgaria to occupy parts of Greece and of Yugoslavia. Bulgaria became one of only three countries (along with Finland and Denmark) that saved its entire Jewish population (around 50,000 people) from the Nazi camps by refusing to comply with a 31 August 1943 resolution.

In early September 1944, the Soviet Union declared war on Bulgaria and invaded the country, meeting no resistance. This enabled the Bulgarian Communists (the Bulgarian Workers' Party) to seize power and establish a communist state. The new régime turned Bulgaria's forces against Germany. The 450,000-man army of 1944 dwindled to 130,000 by 1945. However, the authorities[who?] deported almost the entire Jewish population of the Bulgarian-occupied Yugoslav and Greek territories to the Treblinka death camp in Poland.

The People's Republic of Bulgaria

In World War II Bulgaria had again allied itself with Germany following the promise[citation needed] of the return of Macedonia. On September 8, 1944 the USSR declared war on Bulgaria and crossed the Danube. Bulgarian army officers and partisan brigades joined forces with the Soviets and Sofia fell. On the next day the invading forces took the rest of Bulgaria. (9 September became known as "Liberation Day".) The Fatherland Front took over the government and the Communist party increased its membership from 15,000 to 250,000 during the following six months.

After World War II, Bulgaria fell within the Soviet sphere of influence. It became a People's Republic in 1946 and one of the USSR's staunchest allies. Bulgaria and Nigeria established diplomatic relations on March 10, 1964. Since 1970, Bulgaria has an honorary consulate in Abuja. Nigeria is represented in Bulgaria through it embassy in Athens (Greece). In the late 1970s, it began normalizing relations with Greece. The People's Republic ended in 1989 as many Communist regimes in Eastern Europe, as well as the Soviet Union itself, began to collapse. Opposition forces removed the Bulgarian Communist leader Todor Zhivkov and his right-hand man Milko Balev from power on 10 November 1989.

The Republic of Bulgaria

In February 1990, the Communist Party voluntarily gave up its monopoly on power, and in June 1990 free elections took place, won by the moderate wing of the Communist Party (renamed the Bulgarian Socialist Party — BSP). In July 1991, the country adopted a new constitution which provided for a relatively weak elected President and for a Prime Minister accountable to the legislature.

The anti-Communist Union of Democratic Forces took office, and between 1992 and 1994 carried through the privatization of land and industry, but faced massive unemployment and economic difficulties. The reaction against economic reform allowed BSP to take office again in 1995, but by 1996 the BSP government had also encountered difficulties, and in the presidential elections of that year the UDF's Petar Stoyanov was elected. In 1997, the BSP government collapsed and the UDF came to power. Unemployment, however, remained high and the electorate became increasingly dissatisfied with both parties.

Relations with Turkey began to normalise in the 1990s[citation needed].

On 17 June 2001, Simeon II, the son of Tsar Boris III and the former Head of state (as Tsar of Bulgaria from 1943 to 1946), won a narrow victory in democratic elections. The king's party — National Movement Simeon II ("NMSII") — won 120 out of 240 seats in Parliament and overturned the two pre-existing political parties. Simeon's popularity declined during his four-year rule as Prime Minister, and the BSP won the elections in 2005, but could not form a single-party government and had to seek a coalition.

Since 1989, Bulgaria has held multi-party elections and privatized its economy, but economic difficulties and a tide of corruption have led over 800,000 Bulgarians, including many qualified professionals, to emigrate in a "brain drain". The reform package introduced in 1997 restored positive economic growth, but led to rising social inequality. Bulgaria became a member of NATO in 2004 and of the European Union in 2007.

Politics

Bulgaria joined NATO on 29 March 2004 and signed the European Union Treaty of Accession on 25 April 2005.[38][39] It became a full member of the European Union on 1 January 2007. The country had joined the United Nations in 1955, and became a founding member of OSCE in 1995. As a Consultative Party to the Antarctic Treaty, Bulgaria takes part in the administration of the territories situated south of 60° south latitude.[40][41]

Georgi Parvanov, the President of Bulgaria since 22 January 2002, won re-election on 29 October 2006 and began his second term in office in January 2007. (Bulgarian voters directly elect their presidents for a five-year term with the right to one re-election.) The president serves as the head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. He also chairs the Consultative Council for National Security. While unable to initiate legislation other than Constitutional amendments, the President can return a bill for further debate, although the parliament can override the President's veto by vote of a majority of all MPs.

Since 17 August 2005 Sergei Stanishev as Prime Minister has chaired the Council of Ministers, the principal body of the executive branch, which presently[update] consists of 20 ministers. The Prime Minister — usually nominated by the largest parliamentary group — receives the mandate of the President to form a cabinet.

The current[update] governmental coalition comprises the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), National Movement Simeon II (NMSII) and the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (representing mainly the Turkish minority).

The Bulgarian unicameral parliament, the National Assembly or Narodno Sabranie (Народно събрание), consists of 240 deputies, each elected for four-year terms by popular vote. The votes go to parties or to coalition-lists of candidates for each of the 28 administrative divisions. A party or coalition must win a minimum of 4% of the vote in order to enter parliament. Parliament has the responsibility for enactment of laws, approval of the budget, scheduling of presidential elections, selection and dismissal of the Prime Minister and other ministers, declaration of war, deployment of troops outside of Bulgaria, and ratification of international treaties and agreements.

The most recent[update] elections took place in June 2005. The next[update] scheduled elections should take place in summer 2009.

The Bulgarian judicial system consists of regional, district and appeal courts, as well as a Supreme Court of Cassation. In addition, Bulgaria has a Supreme Administrative Court and a system of military courts.

A qualified majority of two-thirds of the membership of the Supreme Judicial Council elects the Presidents of the Supreme Court of Cassation and of the Supreme Administrative Court, as well as the Prosecutor General, from among its members; the President of the Republic then appoints those elected.

The Supreme Judicial Council has charge of the self-administration and organization of the Judiciary.

The Constitutional Court supervises the review of the constitutionality of laws and statutes brought before it, as well as the compliance of these laws with international treaties that the Government has signed. Parliament elects the twelve members of the Constitutional Court by a two-thirds majority: the members serve for a nine-year term. The territory of the Republic of Bulgaria subdivides into provinces and municipalities. In all, Bulgaria has 28 provinces, each headed by a provincial governor appointed by the government. In addition, the country includes 263 municipalities.

In June 2007, the then president of the USA George W. Bush visited Bulgaria for several hours, thus[citation needed] strengthening the relations between the countries.

Military

The military of Bulgaria consists of three services:

- the Bulgarian land forces

- the Bulgarian Navy

- the Bulgarian Air Force

The armed forces have as their patron saint Sveti Georgi (St. George), and Bulgarians celebrate his feast day (6 May) nationally as Valour and Army Day. Despite active participation in all major European wars since the end of the nineteenth century, Bulgarian forces have never lost a flag.[42]

Bulgaria first became a major military power in Europe under Khan Krum and Tsar Simeon I, in a series of wars with the Byzantine Empire for control of the Balkan Peninsula, in the late ninth century. By the use of approximately 12,000 heavy cavalry in tactics resembling those of feudal knights, Simeon I's forces reached as far as the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, in AD 896 . A formal peace treaty lasted until 912, when both sides became engaged in a war which ended with several major defeats of the Byzantines, including one of the bloodiest battles in the Middle Ages at Anchialus in AD 917.

Bulgaria again became a significant military power under the rule of the Asen dynasty in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. During the rule of Tsar Kaloyan (1197-1207) Bulgaria became the first European country to defeat the Crusader knights.[citation needed]

After declaring total independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1908, Bulgaria has functioned as a minor European power, frequently included in plans and wars of the Great Powers. In 1912, the Bulgarian forces invented the world's first aircraft-dropped bombs and soon after became the first military in the world to utilize aviation bombardment, in the siege of Odrin. Thus the Bulgarian Air Force, inheritor of one of the oldest traditions of powered aircraft combat in the world, became an early innovator in aviation military technology and in air-to-surface attack strategies/tactics.

Following a series of reductions beginning in 1989, the active troops of Bulgaria's army number 45,000 today[update]. Reserve forces include 303,000 soldiers and officers. "PLAN 2004", an effort to modernize Bulgaria's armed forces, aims to better meet the perceived military needs of NATO and the European Union.

Bulgarian military personnel have participated in international missions in Cambodia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Afghanistan and Iraq. Starting in 2008, Bulgaria completely abolished compulsory military service. Bulgaria's naval and air forces became fully professional in 2006, and the land forces followed suit at the end of 2008. Bulgaria's Special Forces have conducted missions with the SAS, Delta Force, KSK, and the Spetsnaz of Russia.

In April 2006 Bulgaria and the United States of America signed a defence-cooperation agreement providing for the development of the Bulgarian air bases at Bezmer (near Yambol) and Graf Ignatievo (near Plovdiv), the Novo Selo training-range (near Sliven), and a logistics centre in Aytos as joint US-Bulgarian military facilities. Bulgaria's navy comprises mainly Soviet-era ships, and three submarines. With 354 kilometres (220 mi) of coastline, Bulgaria does not regard assault by sea as a major risk. In the course of recent modernization efforts, Bulgaria purchased a new frigate from Belgium, and the navy seems likely to acquire four Gowind corvettes from the French company DCN. Bulgaria's air forces also use a large amount of Soviet equipment. Plans to acquire transport and attack helicopters are underway, in addition to a major overhaul on old Soviet weapon systems. Military spending accounts for nearly 2.6% of Bulgaria's GDP.[43]

Provinces and municipalities

Between 1987 and 1999 Bulgaria consisted of nine provinces (oblasti, singular oblast); since 1999, it has consisted of twenty-eight. All take their names from their respective capital cities:

The provinces subdivide into 264 municipalities.

Economy

Bulgaria became a member of the European Union in 2007.[44] The World Bank classifies it as an "upper-middle-income economy".[45] Bulgaria has experienced rapid economic growth in recent years[update]. The country continues to rank as the second-poorest member state of the EU,[46] but standards of living have allegedly[update][citation needed] risen.

Due to high-profile allegations of corruption, and an apparent lack of willingness to tackle high-level corruption, the European Union has partly frozen EU funds of about €450 million and may freeze more if Bulgarian authorities do not show solid progress in fighting corruption and in speeding up reforms.[47]

Bulgaria has tamed its inflation since the deep economic crisis in 1996-1997, but latest[update] figures show an increase in the inflation-rate to 12.5% for 2007. Unemployment declined from more than 17% in the mid 1990s to nearly 7% in 2007, but the unemployment-rate in some rural areas continues in high double-digits. Bulgaria's inflation means that the country's adoption of the euro might not take place until the year 2013-2014.[48]

Bulgaria's economy contracted dramatically after 1987 with the dissolution of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON), with which the Bulgarian economy had integrated closely. The standard-of-living fell by about 40%, but it regained pre-1990 levels in June 2004. United Nations sanctions against Yugoslavia and Iraq took a heavy toll on the Bulgarian economy. The first signs of recovery emerged in 1994 when the GDP grew and inflation fell. During the government of Zhan Videnov's cabinet in 1996, the economy collapsed due to lack of international economic support and an unstable banking system. Since 1997, the country has been on the path to recovery, with GDP growing at a 4%–5% rate, increasing FDI, macroeconomic stability and European Union membership.

The former NMSII government elected in 2001 pledged to maintain the fundamental economic policy-objectives adopted by its predecessor in 1997, specifically: retaining the Currency Board, implementing sound financial policies, accelerating privatisation, and pursuing structural reforms. Economic forecasts for 2005 and 2006 predicted continued growth for the economy. Economists predicted annual year-on-year GDP growth for 2005 and 2006 of 5.3% and 6.0% respectively. Forecasters expected industrial output in 2005 to rise by 11.9% from the previous year, and by 15.2% in 2006. Projections of unemployment envisaged 11.5% for 2005, 9% for 2006 and 7.25% for 2007.[49] As of 2006 the GDP structure comprised:

- agriculture 8.0%

- industry 26.1%

- services 65.9%.

Agriculture

Agricultural output has decreased overall since 1989, but production has grown in recent years[update], and together with related industries like food-processing it still plays a key role in the Bulgarian economy. Arable farming predominates over stock-breeding. The country has a lack of modern equipment. Alongside aeroplanes and other equipment, Bulgarian agriculture has over 150,000 tractors and 10,000 combine harvesters.

Production of the most important crops (according to the FAO) in 2006 (in '000 tons) amounted to: wheat 3301.9; sunflower 1196.6; maize 1587.8; grapes 266.2; tobacco 42.0; tomatoes 213.0; barley 546.3; potatoes 386.1; peppers 156.7; cucumbers 61.5; cherries 18.2; watermelons 136.0; cabbage 72.7; apples 26.1; plums 18.0; strawberries 8.8.

Industry

Industry plays a key role in the Bulgarian economy. Although Bulgaria lacks large reserves of oil and gas, it produces significant quantities of electricity. Bulgaria formerly ranked as the most important exporter of electricity in the region[which?] due to the Kozloduy Nuclear Power Plant, which has a total capacity of 2,000 MW, but after the closure of its first four blocks, exports of electricity declined and the country lost its leading position as an energy-supplier for the Balkans. However, the two most modern blocks of the power plant, blocks 5 and 6, continue to run and to provide power. Construction has started[update] on a second plant, the Belene Nuclear Power Plant with a projected capacity of 2,000 MW. Plans exist[update] for a $1.4bn project for construction of an additional 670 MW for the 500 MW Maritza Iztok 1 Thermal Power Plant[50] (see Energy in Bulgaria).

Ferrous metallurgy has major importance. Much of the production of steel and pig iron takes place in Kremikovtsi and Pernik, with a third metallurgical base in Debelt. In production of steel and steel products per capita the country heads the Balkans. Recently the fate of Kremikovtsi steel factories has come under debate, because of serious pollution of the capital, Sofia.

The largest refineries for lead and zinc operate in Plovdiv (the biggest refinery between Italy and the Ural mountains), Kardzhali and Novi Iskar; for copper in Pirdop and Eliseina; for aluminium in Shumen. In production of many metals per capita, Bulgaria ranks first in South Eastern Europe.

About 14% of the total industrial production relates to machine-building, and 24%[citation needed] of the people work in this field. Its importance has decreased since 1989.

Electronics and electric equipment-production have developed to a high degree. The largest centres include Sofia, Plovdiv and the surrounding area, Botevgrad, Stara Zagora, Varna, Pravets and many other cities. These plants produce household appliances, computers, CDs, telephones, medical and scientific equipment.

Many factories producing transportation equipment currently[update] do not operate at full capacity. Plants produce trains (Burgas, Dryanovo), trams (Sofia), trolleys (Dupnitsa), buses (Botevgrad), trucks (Shumen), motor trucks (Plovdiv, Lom, Sofia, Lovech). Lovech has an automotive assembly plant. Rousse serves as the main centre for agricultural machinery. Most Bulgarian shipbuilding takes place in Varna, Burgas and Rousse. Bulgarian arms production mainly operates in central Bulgaria (Kazanlak, Sopot, Karlovo).

Foreigners seeking additional homes have recently[update] boosted the Bulgarian properties market. Buyers come from across Europe, but mostly from the United Kingdom, encouraged by relatively cheap property-prices and the country's easy accessibility via air-travel.[51]

Science, technology and telecommunications

Some multinational companies have set up regional offices and headquarters in Bulgaria, most notably Hewlett-Packard, which built its Global Service Centre for Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA) in Sofia.

Telecommunications has become one of the growing industries in the country. Three GSM mobile-telephone operators — Globul, Mtel and Vivatel — provide almost 100% coverage each. They have a network of service-centers throughout the country. Bulgarians made use of some 10 million cellular phones[52] as of 2006. Mobikom provides the only NMT 450 mobile-phone service. Bulgarians in towns can access the Internet, and recently[update] most villages have acquired fast connectivity and VoIP; BTK offers DSL connection in larger cities. Bulgaria had about 298,781[53] Internet hosts as of 2007.

Bulgaria supplied many scientific and research instruments for the Soviet space-program, and also sent two men into space: Georgi Ivanov on Soyuz 33 (1979) and Alexander Alexandrov on Soyuz TM-5 (1988). The country participates in India's lunar exploration satellite, Chandrayaan-1. Bulgaria became one of the first European countries to develop serial production of personal computers (Pravetz series 8) in the beginning of the 1980s, and has experience in pharmaceutical research and development.

John Vincent Atanasoff (1903-1995), an American physicist of Bulgarian heritage, invented the first electronic digital computer, a special-purpose machine that became known as the Atanasoff–Berry Computer.

Asen Yordanov (1896-1967), the founder of aeronautical engineering in Bulgaria, worked as an aviator, engineer and inventor; he also contributed to the development of aviation in the United States. He played a significant role in U.S. aircraft development and took part in many other projects.

The Bulgarian-American inventor and scientist Peter Petroff became best known for his work in NASA. Petroff also invented the first digital watch (1970).[54]

U.S. chemist Carl Djerassi, who developed the first oral contraceptive pill (OCP), has Bulgarian ancestry.

The Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, the leading scientific institution in the country, employs most of Bulgaria's researchers working in its numerous branches.

Bulgaria hosts two major astronomical observatories: the Rozhen Observatory, the largest in Southeastern Europe, and the Belogradchik Observatory with three telescopes; as well as several "public astronomical observatories" with planetaria, focused on educational and outreach activities.

Transport

Bulgaria occupies a unique and strategically important geographic location. Since ancient times, the country has served as a major crossroads between Europe, Asia and Africa. Five of the ten Trans-European corridors run through its territory. Bulgaria's roads have a total length of 102,016 km (63,390 mi), 93,855 km (58,319 mi) of them paved and 441 km (274 mi) of them motorways. The country has several motorways in planning, under construction, or partially built: Trakiya motorway, Hemus motorway, Cherno More motorway, Struma motorway, Maritza motorway and Lyulin motorway.

Other planned motorways await finalisation of their routes. They include a link between the capital Sofia and Vidin, a link between the Struma and Trakiya motorways south of Rila Mountain, a link between Rousse and Veliko Tarnovo, and the Sofia ringroad. Many roads have recently[update] undergone reconstruction. As of 2009[update] Bulgaria has 6,500 km (4,000 mi) of railway track, more than 60% electrified. A €360,000,000 project exists for the modernisation and electrification of the Plovdiv-Kapitan Andreevo railway. The only high-speed railway in the region, between Sofia and Vidin, will operate by 2017, at a cost of €3 000 000 000.[55] Air transportation has developed relatively comprehensively. Bulgaria has five official international airports — at Sofia, Burgas, Varna, Plovdiv and Gorna Oryahovitsa. Massive investment plans exist for the first three. Important domestic airports include those of Vidin, Pleven, Silistra, Targovishte, Stara Zagora, Kardzhali, Haskovo and Sliven. After the fall of communism in 1989, most of them are not used as the importance of domestic flights declined. There are many military airports and agricultural airfields. 128 of the 213 airports in Bulgaria are paved. The ports of Varna and Burgas are by far the most important and have the largest turnover. Other than Burgas, Sozopol, Nesebar and Pomorie are big fishing ports. The largest ports on the Danube River are Rousse and Lom which serves the capital. The cities and many smaller towns have well-organised public transport systems, using buses, trolleys (in about 20 cities) and trams (in Sofia). The Sofia Metro in the capital has three planned lines with total length of about 48 km (30 mi) and 52 stations, but much currently[update] remains uncompleted.

Demographics

According to the 2001 census,[56] Bulgaria's population consists mainly of ethnic Bulgarian (83.9%), with two sizable minorities, Turks (9.4%) and Roma (4.7%). Of the remaining 2.0%, 0.9% comprises some 40 smaller minorities, most prominently in numbers the Russians, Armenians, Vlachs, Jews, Crimean Tatars and Sarakatsani (historically known also as Karakachans). 1.1% of the population did not declare their ethnicity in the latest census in 2001.

The 2001 Bulgarian census defines an ethnic group as a "community of people, related to each other by origin and language, and close to each other by mode of life and culture"; and one's mother tongue as "the language which a person speaks best and which is usually used for communication in the family (household)".[57]

| Native Language | By ethnic group | By mother tongue | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulgarian | 6 655 000 | 6 697 000 | 84.46% |

| Turkish | 747 000 | 763 000 | 9.62% |

| Gypsies (roma) | 371 000 | 328 000 | 4.13% |

| Others | 69 000 | 71 000 | 0.89% |

| Total | 7 929 000 | 7 929 000 | 100% [57] |

Most Bulgarians (82.6%) belong, at least nominally, to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, the national Eastern Orthodox Church. Other religious denominations include Islam (12.2%), various Protestant denominations (0.8%) and Roman Catholicism (0.5%); with other denominations, atheists and undeclared totalling approximately 4.1%.[58]

In recent[update] years Bulgaria has had one of the slowest population growth-rates in the world. Negative population growth has occurred since the early 1990s,[59] due to economic collapse and high emigration. In 1989 the population comprised 9,009,018 people, in 2001 7,950,000 and in 2009 7,606,000.[60] Now[update] Bulgaria faces a severe demographic crisis: the population has a fertility-rate of 1.48 children per woman as of 2008, with a predicted rate of 1.7 by the end of 2050. The fertility-rate will need to reach 2.2 to restore natural growth in population.

Culture

Bulgaria functioned as the hub of Slavic Europe during much of the Middle Ages, exerting considerable literary and cultural influence over the Eastern Orthodox Slavic world by means of the Preslav and Ohrid Literary Schools. Bulgaria also gave the world the Cyrillic alphabet, the second most-widely used alphabet in the world, which originated in these two schools in the tenth century AD.

A number of ancient civilizations, most notably the Thracians, Greeks, Romans, Slavs, and Bulgars, have left their mark on the culture, history and heritage of Bulgaria. The country has nine UNESCO World Heritage Sites:

- The early medieval large rock relief Madara Rider

- two Thracian tombs (one in Sveshtari and one in Kazanlak)

- three monuments of medieval Bulgarian culture (the Boyana Church, the Rila Monastery and the Rock-hewn Churches of Ivanovo)

- two examples of natural beauty: the Pirin National Park and the Srebarna Nature Reserve

- the ancient city of Nesebar, a unique combination of European cultural interaction, as well as, historically, one of the most important centres of seaborne trade in the Black Sea

Note also the Varna Necropolis, a 3500-3200BC burial-site, purportedly containing the oldest examples of worked gold in the world.

Bulgaria's contribution to humanity continued throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with individuals such as John Atanasoff — a United States citizen of Bulgarian descent, regarded as the father of the digital computer. A number of noted opera-singers (Nicolai Ghiaurov, Boris Christoff, Raina Kabaivanska, Ghena Dimitrova, Anna Tomowa-Sintow, Vesselina Kasarova), pianist Alexis Weissenberg, and successful artists (Christo Yavashev, Pascin, Vladimir Dimitrov) popularized the culture of Bulgaria abroad.

One of the best internationally-known artists, Valya Balkanska sang the song Izlel e Delyu Haydutin, part of the Voyager Golden Record selection of music included in the two Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977. The Bulgarian State Television Female Vocal Choir also known as Mystery of Bulgarian voices has also attained a considerable degree of fame.

A characteristic custom called nestinarstvo distinguishes the Strandzha region. The custom involves dancing into fire or over live embers.

Music

Regional musical styles abound in Bulgaria. Dobrudzha, Sofia, Rodopi, Macedonia, Thrace and the Danube shore all have distinctive sounds. Folk music revolved around holidays like Christmas, New Year's Day, midsummer, and the Feast of St. Lazarus, as well as the Strandzha region's unusual Nestinarstvo rites, in which villagers fell into a trance and danced on hot coals as part of the joint feast of Saints Konstantin and Elena on May 21. Music also formed a part of more personal celebrations such as weddings. Singing has a long tradition for both men and women. Women often sang songs at work parties such as the sedenka (often attended by young men and women in search of partners to court), betrothal ceremonies, and just for fun. Women had an extensive repertoire of songs that they sang while working in the fields. Young women eligible for marriage played a particularly important role at the dancing in the village square (which not too long ago[update] represented the major form of "entertainment" in the village and formed a very important social scene). The dancing — every Sunday and for three days on major holidays like Easter — began not with instrumental music, but with two groups of young women singing, one leading each end of the dance line. Later on, instrumental musicians might arrive and the singers would no longer act as the dance leaders. Singers performed laments not only at funerals but also upon the departure of young men for military service.

The Sofia-based State Ensemble for Folk Songs and Dances, led by Philip Koutev (1903-1982), became the most important state-supported orchestra of this era[which?]. Koutev became perhaps

This article possibly contains original research. (January 2009) |

the most influential musician of 20th-century Bulgaria, and updated rural music with more accessible harmonies to great domestic acclaim. In 1951, Koutev founded the group known today[update] as the Bulgarian State Television Female Vocal Choir, which became famous worldwide after the release of a series of recordings entitled Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares.

The distinctive sounds of women's choirs in Bulgarian folk music come partly from their unique rhythms, harmony and polyphony, such as the use of close intervals like the major second and the singing of a drone accompaniment underneath the melody, especially common in songs from the Shope region around the Bulgarian capital Sofia and the Pirin region. In addition to Koutev, who pioneered many of the harmonies, and composed several songs which other groups (especially Tedora) covered, various women's vocal groups gained popularity, including Trio Bulgarka, consisting of Yanka Roupkina, Eva Georgieva, and Stoyanka Boneva, some of whom appeared in the "Mystery of the Bulgarian Voices" tours.

Cuisine

Owing to the relatively warm climate and diverse geography affording excellent growth conditions for a variety of vegetables, herbs and fruits, Bulgarian cuisine (Bulgarian: българска кухня, bulgarska kuhnya) offers great diversity.

Famous for its rich salads required at every meal, Bulgarian cuisine also features diverse quality dairy products and a variety of wines and local alcoholic drinks such as rakia, mastika and menta. Bulgarian cuisine features also a variety of hot and cold soups, for example tarator. Many different Bulgarian pastries exist as well, such as banitsa, a traditional pastry prepared by layering a mixture of whisked eggs and pieces of sirene (Bulgarian Feta cheese) between filo pastry and then baking it in an oven.

Traditionally, Bulgarian cooks put lucky charms into their pastry on certain occasions, particularly on Christmas Eve, the first day of Christmas, or New Year's Eve. Such charms may include coins or small symbolic objects (such as a small piece of a dogwood branch with a bud, symbolizing health or longevity). More recently[update], people have started writing happy wishes on small pieces of paper and wrapping them in tin foil. Wishes may include happiness, health, or success throughout the new year.

Bulgarians eat banitsa — hot or cold — for breakfast with plain yogurt, ayran, or boza. Some varieties include banitsa with spinach (spanachena banitsa) or the sweet version, banitsa with milk (mlechna banitsa) or pumpkin (tikvenik). Certain entries, salads, soups and dishes go well with alcoholic beverages, especially Bulgarian wine.

Tourism

In the northern-hemisphere winter, Samokov, Borovets, Bansko and Pamporovo become well-attended ski-resorts. Summer resorts exist on the Black Sea at Sozopol, Nessebur, Golden Sands, Sunny Beach, Sveti Vlas, Albena, Saints Constantine and Helena and many others. Spa resorts such as Bankya, Hisarya, Sandanski, Velingrad, Varshets and many others attract visitors throughout the year. Bulgaria has started[update] to become an attractive tourist destination because of[citation needed] the quality of the resorts and prices below those found in Western Europe.

Bulgaria has enjoyed a substantial growth in income from international tourism over the past decade[update]. Beach-resorts attract tourists from Germany, Romania, Russia, Scandinavia, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. The ski-resorts have become a favourite destination[citation needed] for British and Irish tourists.

As a country with a historical and cultural heritage, and attractive natural landscapes, Bulgaria has become one of the most visited[citation needed] tourist destinations in Europe. Tourism, as an industry, has proved an important source of economic growth.[citation needed] In 2007 5.2 million tourists visited, measured as outlined by the World Tourism Organization.[citation needed] Tourists from the top three countries of origin — Greece, Romania and Germany — account for[when?] 40% of all visitors. In 2008 the Bulgarian Tourism Agency expected to welcome an estimated 6 million visitors.[61]

The country has historical cities and towns, summer beaches, and mountain ski resorts. New types of tourism, including cultural, architectural and historic tours, eco-tourism, and adventure tours, expand the range of services available to visitors. Winter tourist centres, such as Borovetz, Bansko, Pamporovo and Vitosha provide picturesque and popular ski resorts. The Bulgarian summer resorts along the Black Sea coast include destinations such as the summer resorts: Sozopol, Nessebur, Golden Sands, Sunny Beach, Sveti Vlas, Albena and St. St. Constantine & Helena. Some guests, such as the Germans, Russians or Scandinavians, favour the summer beach resorts, while winter tourism, and the ski resorts, have become the favorites of the British.

Emerging types of tourist activities, such as "ethno-tourism" and "architectural-cultural" tourism, increasingly gain ground[when?], catering to specialized tastes. These new types of tours involve interaction with and living amongst the local people in small mountain villages.

For the more adventurous, active recreation, involving mountain hiking and bike tourism, provides a close connection with nature. Climbers scale the granite mountains of Rila, Pirin and the Balkan. Hikers enjoy the mountains of Vitosha and the Rhodopes - the latter the mythical birthplace of Orpheus. Mountain biking and bicycle racing also feature. Bulgaria , like only six other countries, annually hosts the official 1,200 km Randonnees — ultra-marathon bicycle rides patterned after Paris-Brest-Paris.

Situated at the crossroads of the East and West, Bulgarian territory has hosted many civilizations - Thracians, Romans, Byzantines, Slavs, Proto-Bulgarians, and Ottomans. Although Bulgaria has many historical artifacts, many of the museums and monasteries still lack proper advertising and maintenance, and tourists may find some of the most interesting heritage sites somewhat inaccessible, due to poor infrastructure. Yet some visitors regard such "underdevelopment" as desirable - those who prefer to experience history first-hand rather than look at artefacts behind glass.

Bulgaria now[update] attracts close to 7 million visitors yearly. Tourism in Bulgaria makes a major contribution towards the country's annual economic growth of 6% to 6.5%.[citation needed]

Sports

UEFA

Football has become by far the most popular sport in Bulgaria. Many Bulgarian fans closely follow the top Bulgarian league, the Bulgarian "A" Professional Football Group; as well as the leagues of other European countries. The Bulgaria national football team achieved its greatest success with a fourth-place finish at the 1994 FIFA World Cup in the United States.

Stiliyan Petrov currently[update] ranks as the most popular[citation needed] Bulgarian footballer. Georgi Asparuhov-Gundi (1943-1971), also became extremely popular at home and abroad, having had offers from clubs in Italy and Portugal, and having won the Bulgarian football player №1 award for the twentieth century.[62] Hristo Stoichkov has arguably become the best-known Bulgarian footballer of all time. His career peaked between 1992 and 1995, while he played for FC Barcelona, winning the Ballon d'Or in 1994. Additionally, he featured in the FIFA 100 rankings. Three Bulgarians have won the European top scorers' Golden Boot award: Stoichkov,Georgi Slavkov and Petar Jekov.

PFC CSKA Sofia (champion of Bulgaria 31 times (As of 2008[update]), National cup holder 13 times, European Cup semi-finalist 2 times, Cup Winners' Cup semi-finalist), PFC Levski Sofia (25 times champion of Bulgaria and 26 times National Cup holder), PFC Slavia Sofia (officially the oldest football- and sports-club in Bulgaria, 8 times football champion of Bulgaria and 12 times holder of the National Cup, Cup Winners' Cup semi-finalist) have become the most successful Bulgarian football-clubs. Other popular clubs include PFC Lokomotiv Sofia, PFC Litex Lovech, PFC Cherno More Varna and PFC Lokomotiv Plovdiv. PFC Levski Sofia became the first Bulgarian team to participate in the modern UEFA Champions League group stage, having achieved this by qualifying for the 2006/2007 competition.

Apart from football, Bulgaria boasts great achievements in a great variety of other sports. Maria Gigova and Maria Petrova have each held a record of three world-titles in rhythmic gymnastics. Other famous gymnasts include Simona Peycheva and Neshka Robeva (a highly successful coach as well). Yordan Yovtchev ranks as the most famous Bulgarian competitor in Artistic Gymnastics. Bulgarians also dominate in weightlifting, with around 1,000 gold medals in different competitions, although cases of doping have occurred among Bulgarian weightlifters, which led to the expulsion of the entire Bulgarian team from the 2000 Summer Olympics, and their voluntary withdrawal from the 1988 Summer Olympics.[63] Stefan Botev, Nickolai Peshalov, Demir Demirev and Yoto Yotov figure among the most distinguished weightlifters. In wrestling, Boyan Radev, Serafim Barzakov, Armen Nazarian, Plamen Slavov, Kiril Sirakov and Sergey Moreyko rank as world-class wrestlers. Dan Kolov became a wrestling legend in the early 20th century after leaving for United States.

Bulgarians have made many significant achievements in athletics. Stefka Kostadinova, who still holds the women's high jump world record, jumped 209 centimetres at the 1987 World Championships in Athletics in Rome to clinch the coveted title. Presently[update], Bulgaria takes pride in its sprinters, especially Ivet Lalova and Tezdzhan Naimova.

Volleyball recently[update] experienced a big resurgence. The Bulgarian national volleyball team, one of the strongest teams in Europe, currently[update] ranks fourth in the FIVB ranklist.[citation needed] At the 2006 Volleyball World Championship this team won the bronze medal.

Chess has achieved great popularity. One of the top chess-masters and a former world champion, Veselin Topalov, plays for Bulgaria. At the end of 2005, both men's and women's world chess-champions came from Bulgaria, as well as the junior world champion.

Albena Denkova and Maxim Staviski have won the ISU world figure skating championships twice in a row (2006 and 2007) for ice-dance.

Bulgarians have also achieved major successes in tennis. The Maleeva sisters: Katerina, Manuela and Magdalena, have each reached the top ten in world rankings, and became the only set of three sisters ranked in the top ten at the same time. Bulgaria has other well-known tennis players such as Tsvetana Pironkova, Sesil Karatancheva and Grigor Dimitrov, who in 2008 became the Wimbledon junior champion and US Open junior chamion.

Bulgaria also has strengths in shooting sports. Maria Grozdeva and Tanyu Kiriakov have won Olympic gold medals, and Ekaterina Dafovska won the Olympic gold in biathlon in the 1998 Winter Olympic Games.

Petar Stoychev set a new swimming world record for crossing the English Channel in 2007.

The country has strong traditions in amateur boxing and in martial-arts competitions. Bulgaria has achieved major success with its judo and karate teams in European and World championships. Kaloyan Stefanov Mahlyanov, best known as Kotoōshū Katsunori, has become well-known worldwide for his sumo prowess.

Religion

Most citizens of Bulgaria have associations — at least nominally — with the Bulgarian Orthodox Church. Founded in 870 AD under the Patriarchate of Constantinople (from which it obtained its first primate, its clergy and theological texts), the Bulgarian Orthodox Church has had autocephalous status since 927. The Orthodox Church re-established the Bulgarian Patriarchate in Sofia in the 1950s after the promulgation of the Bulgarian Exarchate in 1870. The Bulgarian Orthodox Church, as the independent national church of Bulgaria (like the other national branches of Eastern Orthodoxy in their respective countries) plays a role as an inseparable element of Bulgarian national consciousness. The Church became subordinate within the Patriarchate of Constantinople, twice during the periods of Byzantine (1018 – 1185) and Ottoman (1396 – 1878) domination but has been revived every time as a symbol of Bulgarian statehood without breaking away from the Orthodox dogma. In 2001, the Bulgarian Orthodox Church had 6,552,000 members in Bulgaria (82.6% of the population). However, many people raised during the 45 years of communist rule are not religious, even though they may formally be members of the Church.

Despite the dominant position of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church in Bulgarian cultural life, a number of Bulgarian citizens belong to other religious denominations, most notably Islam, Roman Catholicism and Protestantism.

Islam came to Bulgaria at the end of the fourteenth century after the conquest of the country by the Ottomans. It gradually gained ground throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries through the introduction of Turkish colonists and the conversion of native Bulgarians[citation needed]. One Islamic sect, Ahmadiyya, faces problems in Bulgaria. Some officials have moved against Ahmadis[64] on the grounds[64] that other countries - such as Pakistan - also attack the religious rights of Ahmadis, whom many[64] Muslims regard as heretical.

In the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries, missionaries from Rome converted Bulgarian Paulicians in the districts of Plovdiv and Svishtov to Roman Catholicism. Today[update] their descendants form the bulk of Bulgarian Catholics, whose number stood at 44,000 in 2001.

Missionaries from the United States introduced Protestantism into Bulgarian territory in 1857. Missionary work continued throughout the second half of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century. In 2001 Bulgaria had some 42,000 Protestants.

According to the most recent Eurostat "Eurobarometer" poll, in 2005,[65] 40% of Bulgarian citizens responded that "they believe there is a God", whereas 40% answered that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force", 13% that "they do not believe there is a God, spirit, nor life force", and 6% did not answer.

See also

- List of Bulgarian monarchs

- History of Communist Bulgaria

- Bulgarian resistance movement during World War II

Notes

- ^ "CIA - The World Factbook - Bulgaria". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ "Bulgaria (07/08)". State.gov. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ a b c d "Bulgaria". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ^ This article uses the official Bulgarian transliteration system when romanizing Bulgarian Cyrillic. For details, see Romanization of Bulgarian.

- ^ "The Thracian tomb in Kazanluk". Digsys.bg. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ Crampton, R.J., Bulgaria, 2007, pp.174, Oxford University Press

- ^ Donchev, D. (2004). Geography of Bulgaria (in Bulgarian). Sofia: ciela. p. 68. ISBN 954-649-717-7.

- ^ Head Direction of Residential Registration and Administrative Service. Population table by permanent and present address as of 15 March 2008.

- ^ a b c s:1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Bulgaria/History

- ^ a b c Bakalov, Georgi. Little known facts of the history of ancient Bulgarians. Science Magazine. Union of Scientists in Bulgaria. Vol. 15 (2005) Issue 1. (in Bulgarian). This lengthy paper reaches two main conclusions: 1. The native land of ancient Bulgars lies in the region of the rivers Amu Darya and Sar Darya, Pamir, and Bactria, known also as Balhara. 2. The Bulgar language, relatively self-contained, features Iranian roots and Pamir-Fergana lexemes.

- ^ a b c Dimitrov, Bozhidar. Bulgarians and Alexander of Macedon. Sofia: Tangra Publishers, 2001. 138 pp. (in Bulgarian) ISBN 9549942295

- ^ a b c Dobrev, Petar. Unknown Ancient Bulgaria. Sofia: Ivan Vazov Publishers, 2001. 158 pp. (in Bulgarian) ISBN 9546041211

- ^ Zlatarski, pp. 146-153

- ^ a b Bojidar Dimitrov: Bulgaria Illustrated History. BORIANA Publishing House 2002, ISBN 9545000449

- ^ Runciman, p. 26

- ^ C. de Boor (ed), Theophanis chronographia, vol. 1. Leipzig: Teubner, 1883 (repr. Hildesheim: Olms, 1963), 397, 25-30 (AM 6209)"φασί δε τινές ότι και ανθρώπους τεθνεώτας και την εαυτών κόπρον εις τα κλίβανα βάλλοντες και ζυμούντες ήσθιον. ενέσκηψε δε εις αυτούς και λοιμική νόσος και αναρίθμητα πλήθη εξ αυτών ώλεσεν. συνήψε δε προς αυτούς πόλεμον και τον των Βουλγάρων έθνος, και, ως φασίν οι ακριβώς επιστάμενοι, [ότι] κβ χιλάδας Αράβων κατέσφαξαν."

- ^ Runciman, p. 52

- ^ s:Chronographia/Chapter 61

- ^ Georgius Monachus Continuatus, loc. cit. [work not previously referenced], Logomete

- ^ Vita S. démentis

- ^ Barford, P. M. (2001). The Early Slavs. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press

- ^ Fine, The Early Medieval Balkans, pp. 144-148.

- ^ Theophanes Continuatus, pp. 462—3, 480

- ^ Cedrenus: II, p. 383

- ^ Leo Diaconus, pp. 158-9

- ^ Шишић [Šišić], p. 331

- ^ Skylitzes, p. 457

- ^ Zlatarski, vol. II, pp. 1-41

- ^ Averil Cameron, The Byzantines, Blackwell Publishing (2006), p. 170

- ^ Jiriček, p.295

- ^ Jiriček, p. 382

- ^ Lord Kinross, The Ottoman Centuries, Morrow QuillPaperback Edition, 1979

- ^ a b c R.J. Crampton, A Concise History of Bulgaria, 1997, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-567-19-X

- ^ a b D. Hupchick, The Balkans, 2002

- ^ Crampton, R.J. Bulgaria 1878-1918, p.2. East European Monographs, 1983. ISBN 0880330295.

- ^ Kemal H. Karpat, Social Change and Politics in Turkey: A Structural-Historical Analysis, BRILL, 1973, ISBN 9004038175, pp. 36-39

- ^ Dennis P. Hupchick: The Balkans: from Constantinople to Communism, 2002

- ^ "NATO Update: Seven new members join NATO". 2004-03-29. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ "European Commission Enlargement Archives: Treaty of Accession of Bulgaria and Romania". 2005-04-25. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ The Antarctic Treaty system: An introduction. Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR).

- ^ Signatories to the Antarctic Treaty. Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR).

- ^ "History of Bulgaria". Motoroads.com. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ "Bulgaria Military 2007". Theodora.com. 2007. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^

Bos, Stefan (01 January 2007). "Bulgaria, Romania Join European Union". VOA News. Voice of America. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^

"World Bank: Data and Statistics: Country Groups". The World Bank Group. 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ GDP per capita for 2008

- ^

AFP News Briefs (2008-03-28). "Barroso slams Bulgaria's rampant corruption". France 24. AFP. Retrieved 2008-10-15.

"High-level corruption and organised crime have no place in the European Union and cannot be tolerated," Barroso said after talks with Prime Minister Sergey Stanishev... Barroso arrived on a one-day visit to Sofia on Friday amid a high-level corruption scandal that has shaken Stanishev's centre-left government... Bulgaria joined the European Union in 2007 but continues to face strong criticism from Brussels for failing to root out high-level corruption and put well-known criminal bosses behind bars. Corruption concerns also prompted Brussels recently to partly freeze pre-accession subsidy payments of at least 450 million euros still due to the EU newcomer.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessdaymonth=,|accessyear=,|accessmonthday=, and|coauthors=(help); line feed character in|quote=at position 505 (help) - ^

Koinova, Elena (2008-05-12). "Bulgaria to adopt the euro in 2013-2014, UniCredit says". Sofia Echo. Sofia Echo Media Ltd. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

Bulgaria and Romania would likely join the euro zone in 2013-2014, the analytical unit of UniCredit Group said in its latest report titled The Euro goes Eastwards.

- ^ Associated, The. "Bulgaria's economy grew by 6.2 percent on year in 1Q - International Herald Tribune". Iht.com. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ ":Alstom.CZ - Power Environment Sector:". Alstom.cz. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ A very Bulgarian building boom BBC

- ^ "Bulgaria Communications 2007". Theodora.com. 2007. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ Statistics of Bulgarian communications

- ^ www.allbusiness.com - "Peter Petroff, Digital Watch Inventor, Dies at Age 83". Compare the [http://www.engology.com/eng5nakamatsu.htm claim of Yoshiro Nakamatsu to have invented a digital watch in 1953.

- ^ Влак-стрела ще минава през Ботевград до 2017 г.

- ^ National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria. Retrieved 31 July 2006

- ^ a b Cultrual Policies and Trends in Europe. "Population by ethnic group and mother tongue, 2001". Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ "Bulgaria".