Laminium

| Laminio | |

|---|---|

| Former subdivision of Roman Empire | |

| Demonym | Oretans |

| Area | |

| • Coordinates | 39°05′54″N 2°29′32″O |

| • Type | municipium iuris latini |

| History | |

• Established | VI century - III century B.C. |

| Today part of | There is speculation that • Alhambra (royal city) • Daimiel (royal city) • Site located between the TMs of Villarrobledo and El Bonillo (Albacete). |

Laminium was an Iberian oppidum (fortified city), the southernmost of the Carpetan tribe and head of the Ager Laminitanus.[1] Pliny the Elder and Ptolemy make references to it on several occasions.

The Roman Laminium acquired the status of Flavian municipality (municipio flavio), with the privileges that it entailed, like other cities such as Complutum, Toletum or Consaburum, which leads us to believe that it would have a certain importance in terms of civil and religious works. It was also part of the main Roman road network, as an important communications hub. In the so-called Itinerary of Antoninus it is located[2] on the roads:

- XXIX, Caesaraugusta-Augusta Emerita.

- XXX, Laminio-Toletum.

- XXXI, Laminio-Libisosa.

Currently the most widespread theory is that Laminium is located in the current urban area of Alhambra. However, since ancient times there have been other hypotheses about its location, so there is a certain legend in La Mancha of a "lost city" around it that has fueled interest in its search and perhaps has magnified its real importance. The latest archaeological excavations in Alhambra reveal the existence of a large oppidum.

Classical testimonies

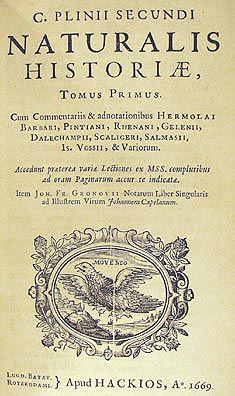

Pliny

Pliny refers,[3] among the most important communities of the conventus carthaginensis, to the consaburenses (Consabura), the egelestani (Egelesta), the laminitani (Laminium), the segobrigenses (Segóbriga), who form the "head" of Celtiberia and the toletani (Toletum), who form the "head" of Carpetania. Likewise, he affirms[4] that the river Anas (Guadiana) rises in the Laminitanian countryside.

In northwest direction, and if we consider the usual equivalence of 1 Roman mile = 1480 meters, the Itinerary of Antoninus places Laminio at about 11 km (7 Roman miles) from Caput Fluminis Anae (on the Libisosa-Laminio road) and this mansion at 21 km (14 Roman miles) from Libisosa (today's Lezuza). The name of this mansion is in accusative, which may suggest that it would be a point on the road from where a road to the source of the Guadiana River would start and not necessarily a town located at the headwaters of the Anas River.

Due to its proximity to Laminio and to a safe location (Lezuza), the location of this place has been one of the main objectives of the researchers as a previous step to the discovery of the city. But it has also turned out to be one of the most important sources of controversy, since to this day people are still trying to determine where exactly the river rises. In fact, the theories that locate Laminio in Alhambra and Daimiel take into account the proximity to the place where one of the sources of the Guadiana (Ojos del Guadiana) is located, but they ignore the excessive distance (more than 70 km) with Lezuza, alleging medieval translation errors. Such a considerable distance is not a trivial matter and seems difficult to assume for a people as pragmatic as the Romans, since it is almost double what it is considered that one could travel in that time in one day.

Based on works from the Muslim and medieval periods, other authors determine that, as for the Romans, the sources of the Anas River would have been located in the Córcoles-Sotuélamos system or in the Lagunas de Ruidera (Alto Guadiana). Paleogeography and archeology seem to support those who maintain these theses, since they affirm that the area, in ancient times, provided much more water to the Anas than it does today. It is even claimed that the Záncara constituted for millennia the true upper course of the river.

A Caput Fluminis Anae and a Laminio in the surroundings of the Córcoles would solve the problem of the distances for the Routes XXIX and XXXI of the Itinerary of Antoninus. On the other hand, it would create the problem of fitting the distances of Via XXX (the one to Toletum), which is the shortest and has two perfectly located mansions. To solve this problem, Gonzalo Arias suggested several possibilities:

- That the "Limini" of Via XXX is a different mansion from the "Laminio" of Via XXXI.

- That the "Limini" of Via XXX refers to the limit (Lamine in Latin) of the municipality of Laminio (not to the urban enclave) and in reality this road runs between Toledo and that point (Junction theory).

- That intermediate mansions are missing in the original text, possibly from very early times and the different later copyists have amended and squared the distances.

Pliny[5] also suggests that the Laminitanian sharpening stones were the best of their kind in the whole Empire.

Theories about its location

Throughout history, the city of Laminium has been located in many different places within a very large area that, although entirely in the natural region of La Mancha, covers parts of the provinces of Ciudad Real and Albacete. Nowadays, universities and academies reduce Laminium to the current municipality of Alhambra. However, since ancient times there has been a tradition of local historians who have tried to reduce it to other points. Thus, a site has been proposed in the vicinity of Daimiel or in another site located between the municipalities of El Bonillo and Villarrobledo, in the province of Albacete.

Western Laminio (near Daimiel)

Rodríguez Morales locates Laminio in the city of Daimiel. He argues in favor of its proximity to one of the places considered to be the source of the Guadiana River and its location near the Tablas de Daimiel, suggesting that, etymologically, Laminio would mean something similar to 'city of the lakes' or 'the marshes'. Likewise, it is maintained that the current name of Daimiel is nothing more than a phonetic corruption of Laminio.

Against this theory is adduced the excessive distance that exists from Libisosa (more than 70 km), the fact of having taken into account a modern hypothesis of the source of the Guadiana River, the lack of certainty about the etymology of Laminio and the little Roman archaeological evidence in the area. This theory is very unlikely, since we should presume an excessive error in the calculation of the distances from Lezuza. In addition, the etymology of the name of the city is highly disputed and there is very little evidence supporting the city of the marshes.

The central Laminium (Alhambra)

It is currently the most accepted theory by specialists thanks to Alföldy's work on the Roman presence in Hispania. It locates Laminio in the current urban area of Alhambra (Ciudad Real) and is based on the existence of important Roman vestiges in its area. This theory has been recently supported by the studies of Luis Andrés Domingo Puertas. The success of the theory of Luis Andrés Domingo Puertas has allowed a breakthrough in the knowledge of Roman antiquity in Ciudad Real, with studies such as those of Moya-Maleno (2008), Benítez de Lugo or Gómez Torrijos (2011). In its defense, we find that the location of Alhambra corresponds to the model of Oppida Carpetanos, numerous remains of Roman pedestals, inscriptions, statues and two necropolises have been discovered in the urban area, indicating that the place was a municipality in the Flavian period. Also in the vicinity there have existed until recently several sandstone quarries, especially that of the Molares that in the XIX century were still used to sharpen barber's tools and weapons.[6] Alhambra also shares acceptable distances with Caput Flumini Anae (Lagunas de Ruidera) and with Libisosa, in addition to having a road that, effectively, goes to Consuegra on one side and, on the other, to Cástulo through Barranco Hondo. In addition, in its vicinity (El Puerto de Vallehermoso or La Fuenlabrada according to the authors)[7] has been found the only inscription of the entire province that makes direct reference to Laminium. Alhambra has a museum of Roman archaeology and is the only town that exhibits in its main square a set of Roman pedestals and statues.

L-LIVIVS-LVPVS-

GENIO-MVNICI

PI-LAMINITANI

LOCO-DATO-EX

DECRETO-ORDI

NIS-SIGNVM

ARGENTEVM CVM BOMO (sic) SVA

PECVNIA FECIT

IDEMQVE

DEDICAVIT

Inscription from Puerto de Vallehermoso or La Fuenlabrada (E. Hübner, CIL II, 3228)

The references to Laminio may be merely circumstantial since, on many occasions, the remains of abandoned cities were reused in others, as a quarry. In fact, the pedestal with this epigraph is found in Fuenllana (Ciudad Real) since 1530, as we know from the Relaciones histórico-geográfico-estadísticas de los pueblos de España made on the initiative of Felipe II (1575) about this locality:

... and also there is a stone with an old sign in a doorway of a neighbor of this town that is called Juan Patón that was put in the mentioned doorway forty years ago little more or less and the mentioned stone was brought with its sign made of some villares that are where they say the Port of Vallhermoso that will be three leagues from this town.... Topographic Relations of the towns from Spain, made under the command of Philip II (in Spanish: Relaciones histórico-geográfico-estadísticas de los pueblos de España, hechas de orden de Felipe II. Town of Fuenllana)

However, not even the sources agree on the exact location where this epigraph was found, since the Royal Academy of History, in its report[8] on this stone, locates the site in another place, Fuenlabrada, far away and in the opposite direction to Vallehermoso. The identity Fuenllana= Laminio based only on the present location of this epigraph seems, clearly, erroneous. In addition, the place of the Fuenlabrada belongs to the municipality of Montiel. In another epigraph found in the Alhambra itself some authors have wanted to see the name of that important city (it seems that it had abundant civil work) as Anensemarca, although the reading would not support it:

ALLIAE-M-F

CANDIDAE

CVRANTE

LICINIA

MACEDONI

CA-MATRE

COLLEC[c.3]

ANENSEM [c.3]

CUSTOMERS-ET

LIBERTI pat

rONae-POS(uerunt)[9]

Inscription found in Alhambra (E. Hübner, CIL II, 3229)

Another epigraph mentioning Laminium as a municipium flavium was found in La Carolina (Jaén) and has been used, in view of the remains found in Alhambra, as evidence of the correctness of this theory and the erroneous conviction that this would be the only important city in the area.

C-SEMPRONIVS-CELER

CELERI-F-D-D-MVNIC

IPI-BAESVCCITANI

...

MVNICIPIVM-FLAVIVM-LAMINITANVM

D-D-D-LAVDATIONEM-STATVAM

...

Inscription found in La Carolina (Hübner, ad CIL II, 3251)

Against this theory it is also adduced its excessive location to the south and proximity to perfectly located oppida oretanos as Mentesa (Villanueva de la Fuente), the very important Ciudad del Cerro de las Cabezas in Valdepeñas and the capital itself Oretum (Granátula de Calatrava). In fact, and to justify this excessive location to the southwest, there are authors who correct the classics (Ptolemy is the only one who clearly alludes to it as Carpetana) and assure that Laminio was not Carpetana but Oretum and Iberian. It is estimated that Laminio must have maintained close contacts with the southern Iberians due to its geographical location and, if the hypothesis of Marques de Faria is finally proven, due to the fact that it minted coins with iconography similar to those of Castulo and with a legend in southern Iberian labini script.[10]

Other locations that have been proposed within this geographical reduction are Santa María del Guadiana and La Mesa del Cerro del Almendral, in the Lagunas de Ruidera. The second one should be rejected because the remains found suggest the existence of a much older population (Bronze Age), perfectly logical within the very important group of motillas of the Lagunas de Ruidera, with a very scarce Roman survival. The classical authors (Pliny) are very clear in this regard because they claim that the Anas Guadiana is born in the Campo Laminitano, not that the city is there.

The eastern Laminio (between Villarrobledo and Munera)

Already in 1751, Francisco de la Cavallería y Portillo, echoes a secular tradition that locates the Carpetan Laminio within the municipal term of Villarrobledo. However, the historian limits himself to doubt of such assertion without contributing any reliable evidence, neither in favor nor against. Something before, Esteban Perez de Pareja[11] based on Flavio Dextro, remarked the proximity of Laminio to Libisosa, the excellent relations between both cities and assimilated the Ager Laminitanus (Laminian Fields or Arenates) to the Campo de Montiel, without giving a precise location of the city although locating it within this region.

In more recent times (1960s), Enrique García Solana[12] and Gonzalo Arias, based on a detailed study of the Itineraries of Antoninus, locate the Carpetan oppidum in two contiguous places, the first in the municipalities of Villarrobledo and the second in El Bonillo, where the Córcoles River and the Sotuélamos River meet. Currently, and following the same methodology, another author[13] places it further south –in Munera– very close to the Oretano territory. All these locations have the Córcoles River as a common link, in whose banks and in those of its tributaries there are abundant vestiges of settlements and other testimonies of population from very ancient times along its entire route through different municipalities of Albacete and Ciudad Real. In fact, the etymology of the hydronym Córcoles (kurkotz) is considered by specialists to be Iberian and the name of the river from which it flows, the Záncara, has been written –Querzáqqara or Ciudad del Záncara– on a bronze object found in the Fosos de Bayona (Huete).

In these municipalities there are archaeological remains of some substance, which testify to settlements from the Iberian period, earlier –Mousterian and Bronze Age– and later –Roman, Visigothic and Muslim–. The Roman evidence is crystallized, mainly, in abundant fragments of Hispanic terra sigillata, numismatics, cobbled roads and the existence of a Roman bridge over the river Sotuélamos with a width of way perhaps exaggerated for the little entity of the river, although with certain logic if there is a population of certain size. The location of these deposits, perfectly squares the distances of the itineraries XXIX and XXXI and of the XXX taking into account the theory of the junctions. Likewise, from its vicinity starts a Roman road that, coming from the southeast, follows the banks of the Córcoles in a northwest direction and has been suggested as the beginning of Itinerary XXX. Another important nearby route is the one recorded by Villuga in 1540 as Camino Real de Granada a Cuenca, a stretch that has been indicated as Roman by various authors and that would form part of the Camino de los Berones cited by Tito Livio. In addition to these roads, in various places within the municipality of Villarrobledo or in the surrounding areas there are scattered remains of Roman roads and bridges (especially over the Záncara River), suggesting that the area was, in those times, an important communications hub. It must also have had a certain strategic value in pre-Roman times, being a border area between Carpetania, Celtiberia and Oretania.

However, what is currently documented and studied is very little and deficient, and it does not seem to have enough importance and extension to be the great municipality that can be deduced from the classical and epigraphic testimonies and places us rather in front of settlements related to the Culture of the Motillas (of Morra type facies) that were evolving and extending their existence, in some cases, until the Iberian period and in others, until the first Taifas.

On the other hand, a new theory postulates Munera (or its term) as the candidate to lodge in its site the city of Laminio. The sites and settlements in the area –which cover a wide chronology– are numerous (17 of some importance, some of them of cultures hitherto unknown in the area and enormous extension). However, the Roman archaeological evidence is scarce in all of them, according to what a supposedly great Roman municipality of the Flavian period like Laminio should have, being reduced to pottery, numismatics and common use utensils. However, some authors claim that some of the structures found in a known Bronze Age settlement resemble sewers or water conduits, hardly pre-Roman. In addition, the name of the village itself, whose etymology is not clear, is itself a Latin term.

In spite of being one of the most plausible theories and that counts on the support of archaeological vestiges that include a very wide period, the lack at the present time of more conclusive tests (epigraphy mainly) of Roman time, together with the negligence on the part of all the administrations implied in undertaking a study in depth, continues leaving open the enigma and submitting to these deposits to an irremediable plundering.

Causes of their disappearance

If their exact location is a mystery, determining the causes of their disappearance (which would perhaps help to find the city) is even more difficult without finding it. It has been speculated that it was razed during the first years of the Visigothic invasion around 409 A.D. and its remains have been repeatedly plundered; or else, due to its location in marshy areas or near a river, the city succumbed to a terrible flood. In this sense, a location near the Córcoles would be ideal to solve the enigma because this river has a long history of floods (historically documented since the 15th century and when it had much less flow than in the past) that have caused severe damage and have even led to the change of location of two riverside towns like Socuéllamos and Munera, seeking safer places nearby.

Currently, a new hypothesis on "telluric cataclysms" is beginning to be formulated, mainly on the basis of the excavations and archaeological samples that are being studied in the Ibero-Roman city of Libisosa (Lezuza), where wall collapses have been found that are difficult to explain if not for a theory of local seismic movements, affecting at least, in the first instance, the region of eastern Laminium, cited by the Itinerary of Antoninus, and inventoried as A31, where Laminium is cited very close to the headwaters of the Guadiana River, possibly where there was a permanent military garrison, about 10 km away (Caput Fluminius Anae); and the Roman colony of Libisosa, another 21 km away. This theory, which is based on the assumption that whatever happens and is discovered in Libisosa (Lezuza), can be applicable to the eastern Laminium, is what is currently known as the thesis of "The Keys of Lezuza".

See also

Notes

- ^ The ager was the cultivated part of the countryside, according to the classification of spaces of Roman times, which would be equivalent to the current concept of municipal area.

- ^ Most authors consider that all of them refer to the same city, although there is no unanimity.

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Naturalis Historia. III, 25.

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Naturalis Historia. III, 6.

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Naturalis Historia (XXXVI, 47 ed.).

- ^ Moya-Maleno, 2008

- ^ José Cándido de Peñafiel in his 1833 Report to the Real Academia de la Historia on the epigraph is categorical: It was found in La Fuenlabrada (Villahermosa, between Fuenllana and Carrizosa) and not in Puerto de Vallehermoso (Alhambra), however almost all later authors consider the second location to be valid.

- ^ Peñafiel, J. C. de Informe sobre un pedestal honorífico de época romana que se encuentra empotrado en la casa de Diego Tomás Ballesteros en Fuenllana, aunque originariamente apareció en Fuenlabrada, signature CAICR/9/3941/04(4) Archivo de la Real Academia de la Historia, Madrid :1833

- ^ Article by F. Fita in BRAH 1903 on this and other Alhambra inscriptions.[http://descargas.cervantesvirtual.com/servlet/SirveObras/45708400981281653343679/024334.pdf].

- ^ Rodríguez Ramos, J. "Sobre la identificación de la ceca ibérica de Lamini(um)" en Acta Numismática, nº 36: 2006; see also the Labini entry in the Hesperia database.

- ^ Pérez de Pareja, E.. Historia sobre la fundación de Alcaraz: 1740

- ^ García Solana, E. Munera por dentro (Third Ed. 2003). Albacete, Junquera Impresores, 1963

- ^ García Mariana, F.J. En busca de la ciudad perdida: Laminio-Munera Online edition.

Bibliography

- Alföldy, G. Romisches Stadtewesen auf der neukastilischen Hochebene. Ein Testfall fir die Romanisierung, Heidelberg: 1986

- Arias Bonet, G. [[https://web.archive.org/web/*/http://el%20miliario%20extravagante/ dead link] http://www.elnuevomiliario.eu/page22.php], Boletín Trimestral para el Estudio de las Vías Romana y otros Temas de Geografía Histórica

- M.E. n.º 2 (1963): Arias Bonet, G.: El "busilis" del negocio (pp. 19-20)

- M.E. n.º 3 (1963): Arias Bonet, G.(basándose en correspondencia de Gcía Solana): Investigaciones en el Campo Laminitano (pp. 49-59)

- M.E. n.º 6 (1964): Noticias del Campo Laminitano (pp. 138-139)

- M.E. n.º 8 (1965): Carta de Enrique García Solana (pp. 187-188)

- M.E. n.º 10 (1965): Arias Bonet, G.: En busca de la vía de Laminio a Toletum (p. 258)

- M.E. n.º 11 (1966): Arias Bonet, G.: Item a liminio toletum (pp. 288-291)

- M.E. n.º 16 (1968): Arias Bonet, G.: Niebla sobre Laminio (pp. 3-4)

- M.E. n.º 25 (1990): Arias Bonet, G.: Laminio, Sisapone y Titulcia en Alföldy (pp. 5-6)

- M.E. n.º 73 (2000): Rodríguez Morales, J.: Laminium y la vía 29 del Itinerario de Antonino (pp. 16-23)

- M.E. n.º 77 (2001): Fernández Montoro, J. L. -Olcade-: La Pasadilla-Los Castellones (pp. 28-32)

- Arias Bonet, G. Repertorio de Caminos de la Hispania Romana, Pórtico librerías 2ª Edición 2004. Gonzalo Arias, Ronda: 2004.

- Carrasco Serrano, G. Vías romanas y mansiones en el territorio provincial de Albacete en "Actas del IV Congreso de Caminería Hispánica - Tomo I" (pp. 91–102), Guadalajara: 1998.

- Carrasco Serrano, G. Vías romanas y mansiones de la provincia de Toledo: Bases para su estudio en "Actas del IV Congreso de Caminería Hispánica - Tomo I" (pp. 75–86), Guadalajara: 1998.

- Cavallería y Portillo, Francisco de la. Historia de Villa-Robledo, Albacete, IEA-"Don Juan Manuel": 1987 (ed. facsímil, orig.:1751).

- Domingo Puertas, Luis Andrés. En torno al problema de la localización de Laminium en "Hispania Antiqua" n.º 24, Universidad de Valladolid 2000, pp. 45–64

- Fernández Ochoa, C.; Zarzalejos, Mª.M.; Seldas, I.: Entre Consabro y Laminio: aproximación a la problemática de la vía 30 del Itinerario Antonino in "Simposio de la red viaria en la Hispania Romana" (pp. 165–182), Tarazona: 1990.

- Gómez Torrijos, Luis: "Historia de Alhambra. La ciudad Romana de Laminio" Madrid: 2011.

- Gómez Torrijos, Luis: "Inscripciones Romanas de Alhambra y de Laminio. Contribución a la epigrafía romana en Ciudad Real" Biblioteca Oretana. Puertollano. 2011. ("Ciudad Real" award for Historical Research, 2011)

- Benitez de Lugo, Luis: "Arqueología urbana de Alhambra. Investigaciones sobre Laminium" Biblioteca oretana. Puertollano. 2011. ("Alhambra" award for historical research 2011)

- Hübner, E. Corpus inscriptionum Latinarum, II: Inscriptiones Hispaniae Latinae. Berlín, Georg Reimer: 1869.

- Moya-Maleno, P.R. (2008): "Ager y afiladeras. Dos hitos en el estudio del municipio laminitano (Alhambra, Ciudad Real)", in J. Mangas y M.A. Novillo (eds.): El territorio de las ciudades romanas. Sísifo. Madrid. ISBN 978-84-612-8600-3. pp. 557–588.

- Rodríguez Castillo, J.: Los Caminos en Campo de Montiel en Época de Cervantes en "Actas del IV Congreso de Caminería Hispánica - Tomo III" (pp. 1055–1060), Guadalajara: 1998.

- Roldán Hervás, J. M.: Itineraria Hispana. Fuentes antiguas para el estudio de las vías romanas en la Península Ibérica, Valladolid- Granada: 1975

- Sandoval Mulleras, Agustín. Historia de mi pueblo: la muy noble y leal ciudad de Villarrobledo, Albacete: 1961, reed. 2001.